To the Editor:

Although it is uncommon for females with chronic renal failure to become pregnant while on haemodialysis, there is a clear increase in the number of such cases published in the medical literature with a notable success rate, possibly due to the improvements made in dialysis techniques and obstetric care. However, we must not underestimate the risks and complications associated with pregnancy in patients on renal replacement therapy.1-3

Here we report on our experience with a 32-year old female patient with chronic renal failure on a periodical haemodialysis programme and who intended to be pregnant. The patient’s clinical history included: chronic kidney disease secondary to a glomerulopathy that had not been biopsied, arterial hypertension, dyslipidaemia, chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis/sub-centimetre nodular goitre, perennial allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and secondary renal hyperparathyroidism on treatment with cinacalcet.

We immediately modified the patient’s treatment regimen, suspending losartan and atorvastatin and maintaining anti-hypertensive treatment with doxazosin and atenolol. Seven weeks after deciding to become pregnant, the patient developed amenorrhoea, and gestation was confirmed with a positive beta-chorionic gonadotropin blood test. We then proceeded to modify the patient’s dialysis regimen, switching to 6 sessions per week of 4 hours each (24h/week) and haemodiafiltration with endogenous re-infusion. The calcium concentration in dialysate was lowered in order to avoid a positive calcium balance, and the potassium concentration was increased in order to avoid hypopotassaemia. We also modified the concentration of bicarbonate in the dialysate solution, initially lowering it to 25mEq/l in order to avoid metabolic acidosis, but then increasing it to 30mEq/l due to post-haemodialysis metabolic acidosis. For intra-dialytic anti-coagulation therapy, we administered 20mg enoxaparin (intravenous) during each session. Ultrafiltration was limited to 500ml/h in order to avoid sharp decreases in blood pressure, which heavily influences placental perfusion. As regards medical treatment, atenolol and doxazosin were replaced by methyldopa, and omeprazole was replaced by almagate; we reduced the dosage of cinacalcet, which was completely suspended after 7 weeks of gestation due to the lack of information regarding its use in pregnant women. We used calcium acetate as a phosphate binder. As regards other medications, the patient received oral iodine, vitamin C and B complex, folic acid, and carnitine 3 times per week. We did not limit the patient’s dietary intake except for salt restrictions.4,5

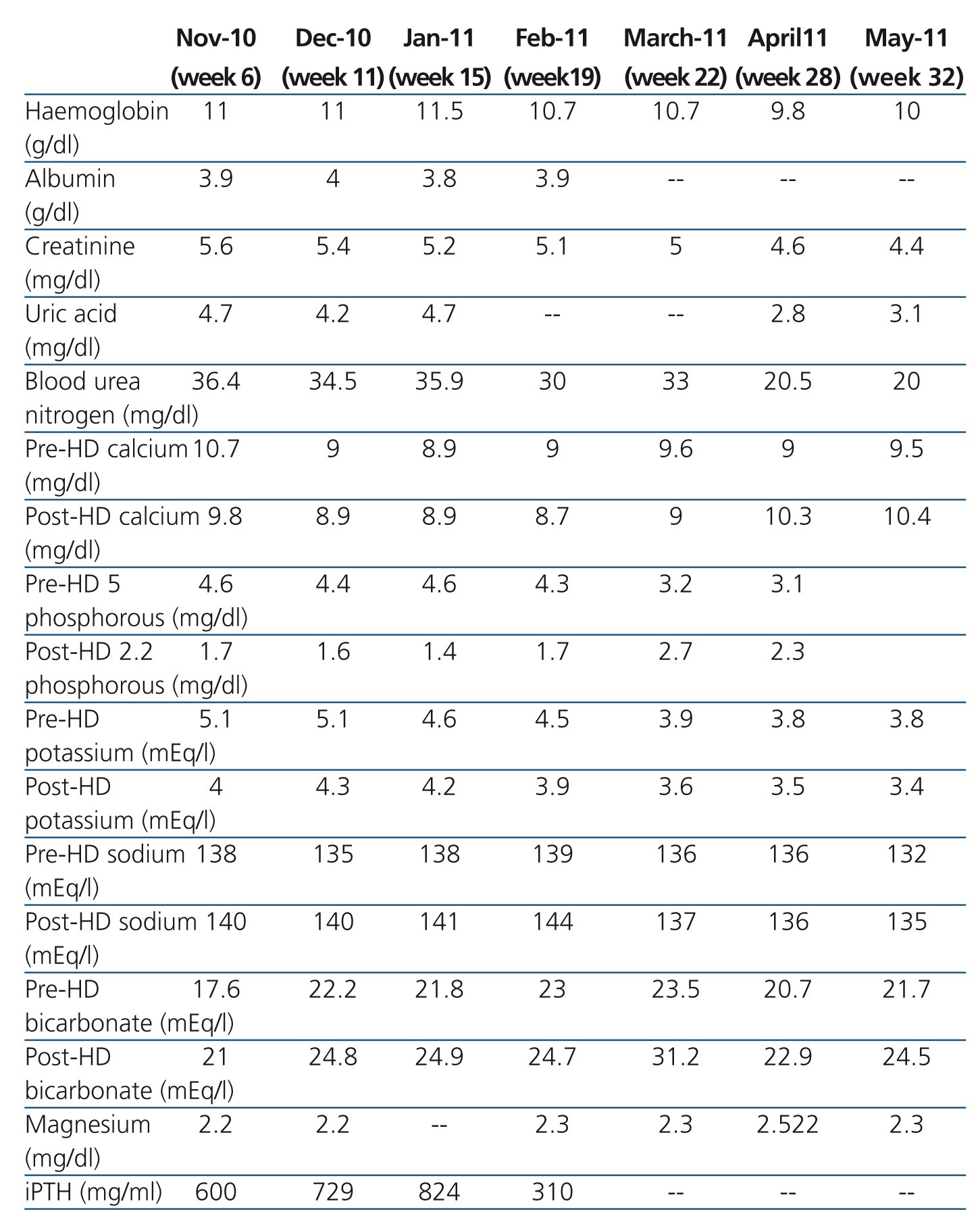

During the first 22 weeks of gestation, the patient received dialysis in a peripheral dialysis centre in collaboration with her reference hospital, and went through regular controls in a high-risk pregnancy consultation. Weekly measurements were taken for haemoglobin, leukocytes and pre-haemodialysis platelets and urea, creatinine, total protein, urea nitrogen, sodium, potassium, phosphorous and pre/post-haemodialysis calcium. We also measured pre/post-haemodialysis acid-base balance every other week.

During this period, it was very difficult to control the patient’s blood pressure, requiring a progressive increase in hypotensive medications, which reached a dosage of 2g/d of methyldopa and 1g/d of labetalol. In week 16 of gestation, we also added diazepam.

In week 20 of pregnancy, the patient was diagnosed with total occlusive placenta pregnancy.

In week 22 of gestation, the patient was admitted to the hospital with a hypertensive crisis and heart failure. From this moment onwards, the patient was treated with 7 sessions of dialysis per week of 4 hours each, and in week 28, the regimen was increased to 6 hours per session, thus reducing the intensity of haemodialysis (blood flow and dialysate flow were programmed to 175ml/minute and 200ml/minute, respectively) in order to achieve better control of body volume and blood pressure. For intra-dialytic anti-coagulation therapy, we switched the patient from enoxaparin to sodium heparin at an initial dose of 15mg and 5mg/hour thereafter. The patient was maintained on a daily haemodialysis regimen until the end of pregnancy. During this period, blood pressure continued to fluctuate, requiring high doses of hypotensive drugs: hydralazine at 100mg/day, methyldopa at 2g/day, and labetalol at 1200mg/day. Given the difficulties in maintaining appropriate blood pressure, the patient was hospitalised until the end of pregnancy.

As regards the treatment of anaemia, the patient’s requirements for erythropoietin (EPO) increased progressively. At the beginning of gestation, we administered a weekly dose of 18 000IU, and by week 22 the dosage had been increased to 30 000IU/week, maintaining haemoglobin values at 10.5-11.5g/dl. During hospitalisation, the dose of EPO was elevated to 42 000IU/week, maintaining haemoglobin values around 10g/dl. The patient also required iron sucrose at 100mg/week throughout the pregnancy. We also administered monosodium phosphate (30mEq) and magnesium sulphate (12mEq) during dialysis,5,6 which was given during the fourth hour of each session; we also gave the patient a banana during the second hour of dialysis as a potassium supplement.

Blood urea nitrogen levels were maintained below 40mg/dl during the entire pregnancy.

The evolution of laboratory parameters is summarised in the Table 1.

In week 23 of pregnancy, the patient gave birth through caesarean due to delayed intra-uterine growth and arterial hypertension, giving birth to a healthy pre-term male of 1.3kg.

The patient gained 230g/week of weight until hospitalisation; afterwards, and despite appropriate intra-uterine growth of the foetus until a few days prior to the caesarean birth, the patient’s weight stabilised and even started to decrease, with a similar weight at week 32 to that recorded at the start of pregnancy. Residual diuresis remained at 800ml/day throughout most of the pregnancy.

In puerperium, the patient developed another episode of heart failure and hypertensive crisis in the context of hydrosaline overload, which was resolved by decreasing dry weight (upon discharge it was 10kg less than at the start of the pregnancy). Coinciding with these findings, we also detected decreased values for haemoglobin, thrombocytopenia, elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and increased transaminase levels in laboratory test results. A peripheral blood smear was normal, ruling out haemolysis. A direct Coombs test was also negative.

Following birth, we observed a complete recovery in clinical and laboratory parameters for the mother, but she still required 6 hypotensive drugs in order to control blood pressure.

Monitoring pregnancy in patients on dialysis requires strict multi-disciplinary control, and we believe that individual experiences and those reported in reviews of case reports are very important for reaching a consensus or shared criterion for managing and treating these patients, so as to achieve a greater rate of success and maternal/foetal survival.7,8

Conflicts of interest

The authors state that they have no potential conflicts of interest related to the content of this article.

Table 1. Evolution of laboratory parameters during pregnancy