A priority for nephrologists in haemodialysis (HD) is preserving their patient venous resources. Vascular access guidelines recommend a prevalence <10% of central venous catheters (CVCs) in HD units. However, this number is increasing at a disquieting rate.1 The main cause of superior vena cava thrombosis in HD is placement of a CVC. The incidence of thrombosis in patients with a CVC ranges from 1% to 66%2–4 depending on the catheter type, catheter location, diagnostic criteria and study population. A very uncommon form of presentation of superior vena cava thrombosis is reported in HD. Very few cases have been reported in the literature.5

We present the case of a 28-year-old male with CKD secondary to reflux nephropathy who started HD at age 11 through a left radiocephalic arteriovenous fistula (AVF). After a decade had passed since he underwent transplantation, he restarted dialysis through a left humeral–cephalic (HC) AVF that thrombosed after resection of an aneurysm and interposition of a PTFE prosthesis. He underwent placement of a right jugular tunnelled venous catheter (CVC), which was removed a year later, once ensured that his right HC-AVF was functioning properly. Incidentally, an angio-CT scan performed for a kidney transplant protocol showed thickening in the distal wall of the oesophagus, and multiple retroperitoneal lymphadenopathies with a diffuse distribution. An endoscopy revealed 3 varicose vessels in the distal third of medium size. Portal vein thrombosis and chronic liver disease were ruled out. The patient started with beta-blockers (nadolol 20mg/24h). At that time, the patient had partial thrombosis of his right HC-AVF, and a PTFE prosthesis was interposed in his old left HC-AVF. Two weeks later, a first episode of acute gastrointestinal bleeding (AGIB) occurred owing to oesophageal varices with severe anaemia (Hb 4.9g/l). It was not possible to perform a haemodynamic study due to an interposition of jugular lymphadenopathies. These were studied along with the retroperitoneal lymphadenopathies that were identified as benign.

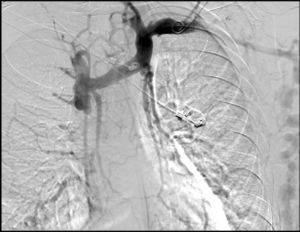

After 10 months had passed since the first episode of AGIB, a second episode occurred. A gastroscopy showed an increase in the number and size of varicose veins (4 varicose veins, 2 of them large). The 2 largest varicose veins were banded with 5 oesophageal bands, but one month later a third episode of AGIB occurred owing to varices. On this occasion, 5 varices were identified, 2 with recent marks of ligation and 3 of medium size. A neck CT scan performed a year earlier, during a lymphadenopathy study, revealed superior vena cava thrombosis, immediately before the cava entered the right atrium, that obliterated the lumen (Fig. 1). He was recannulated using angioplasty, with no complications and with regression of the number and size of the varices (3 of small size). The prothrombotic pathology study was negative. Currently, the patient has been asymptomatic for a year and a half. He undergoes endoscopic monitoring every 6 months, with stabilisation of the varices.

In this case, the aetiology of the oesophageal varices was superior vena cava thrombosis secondary to a catheter, which increased the drainage pressure of the azygos vein and had shifted backwards, causing the varices. An increase in the venous system flow rate, caused by the interposition of a PTFE prosthesis in the old left HC-AVF when partial thrombosis of the right HC-AVF occurred, made the varices increase in number and size, and triggered the first episode of gastrointestinal bleeding a week afterwards.

The placement of a CVC for HD is not free of immediate and late complications. This example of an unusual complication linked to catheters for HD has illustrated the need to avoid their use to the extent possible.

Please cite this article as: Morales García AI, Arenas Jiménez MD, Esteban de la Rosa RJ, Fernández-Castillo R. Varices esofágicas secundarias a trombosis de vena cava superior por catéter yugular para hemodiálisis. Nefrologia. 2016;36:458–459.