Biopsy of both native and transplanted kidneys is an essential procedure for diagnosis in a considerable proportion of kidney diseases,1 although the benefit is more limited if performed in advanced stages of the disease. However, it is not a harmless procedure, and there may present uncommon complications such as haematuria or the need for a nephrectomy/transplantectomy due to organ damage.2

A 61-year-old male with CKD of unknown aetiology who, after 9 months in haemodialysis, received a transplant from a cadaver donor without complications. Seven years later he underwent a graft biopsy because the patient had chronic graft dysfunction and non-nephrotic proteinuria. The biopsy was performed under ultrasound monitoring, with no immediate complications. On the third day, he complained of lumbar pain radiating to the right lower limb, suggestive of lumbar sciatica. On the fourth day, he experienced the onset of oligoanuria and was diagnosed of a perirenal haematoma by ultrasound. He was haemodynamically stable and had pain on palpation of the graft. In a situation of anuria, a limited urine sample was analysed, with low sodium, 47mEq/l and fractional excretion of sodium (FENa)<1%. In the first few hours presented anaemia (Hb of 13g/dl dropped to 10.5–9.6g/dl) and an increase in creatinine (7.41mg/dl) were confirmed. A basic coagulation study was normal. Doppler ultrasound showed a graft of 14×8cm, with an avascular area in the upper pole, dependent on a cortical area of 10×8×7cm, suggestive of a renal haematoma, contained by the renal capsule and without dilatation of the urinary tract; vessels were permeable with normal resistive indices.

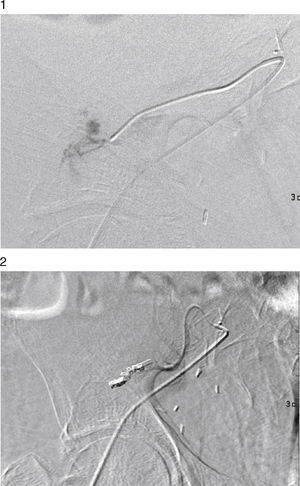

A urologist was consulted owing to suspected active bleeding. The urologist believed that the patient was at high risk of a transplantectomy if surgery was performed, and so it was decided to perform a diagnostic arteriogram with the possibility of embolisation of the bleeding point. Selective renal artery catheterisation was performed through the femoral approach, up to the area of contrast extravasation, with an image suggestive of an AVF, and embolisation of 2 distal branches was performed (Figs. 1 and 2). Afterwards, a urologist drained the parenchymal haematoma of the upper pole and placed haemostatic material. After clinical stabilisation, he required haemodialysis and multiple blood transfusions, and started effective diuresis with improvement in his glomerular filtration rate. A year later, the patient remains stable and has preserved his renal function.

Follow-up of a patient who has received a transplant is essential to prevent, diagnose and treat the complications that may occur during his or her clinical course. Standard biopsy or biopsy indicated in several situations such as suspected acute rejection, chronic dysfunction and proteinuria is a cost-effective procedure.1 However, it is not free of risks, especially in patients with platelet aggregation disorders, on anticoagulants or of advanced age.3

Signs and symptoms of compartment syndrome, or “Page kidney”, have been reported after graft biopsy, which have required surgical decompression and in some cases have led to graft loss. Even after implantation, this clinical picture has also been reported in relation to surgical trauma (renal allograft compartment syndrome, or RACS).4–8 Renal dysfunction is caused by various mechanisms, including compression of the parenchyma due to a subcapsular or intrarenal haematoma and/or with involvement of the hilum, vessels or urinary tract, with the kidney behaving as though renal ischaemia or a urinary obstruction were caused. In any case, it occurs with oligoanuria and its resolution requires release of the compromised organ, in some cases after spontaneous reabsorption of the haematoma9 and in other cases with a surgical procedure,10 provided that there is resolution of the bleeding point.

In our case, the size of the haematoma, the late symptoms (third day) and the drop in haemoglobin, although the patient's haemodynamics were not affected and were perhaps sustained through hyperreninaemia, suggested the possibility of persistent bleeding. As a result, prior action by an angioradiologist, before the surgical procedure, was proposed. After the active bleeding point was identified and embolised, the patient underwent urological surgery in which the haematoma was drained and diuresis and renal function were recovered.

The risk of transplantectomy in a late surgical procedure11 (7th year post-transplant) is high owing to fibrosis and the difficulty of identifying structures and the location of the bleeding point. Prior haemostasis by the endovascular route allowed this risk to be reduced and the haematoma to be drained, with no risk of rebleeding.

Some complications of kidney transplant require an assessment and multidisciplinary action for their resolution, owing to their diagnostic and therapeutic complexity.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Torres Sánchez MJ, Galindo Sacristán P, Pérez Marfil A, de Teresa Alguacil J, Barroso Martín FJ, Osorio Moratalla JM. Anuria tras biopsia del injerto renal: intervención multidisciplinar. Nefrologia. 2016;36:456–457.