Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is an opportunistic virus that affects the majority of immunocompromised patients, including transplant recipients.1 The infection is generally caused by reactivation of a strain in the recipient in a latent state and, more rarely, by infection from an exogenous strain. The period of greatest risk for presenting a CMV infection is during the first 6 months post-transplant. CMV infection is rare starting from the sixth month.2 Since the introduction of new immunosuppressive agents, especially mycophenolate mofetil, an increase in the incidence of CMV infection has been reported.3 However, only exceptionally does a CMV infection start as a serious complication, especially once the first 6 months have passed since the transplant.1 We present the case of a kidney transplant recipient with a long clinical course with low doses of immunosuppressants who developed a severe intestinal disease due to CMV that required emergency surgery.

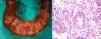

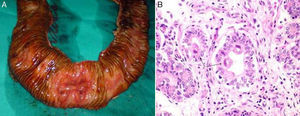

A 65-year-old woman with hypertension and type 2 diabetes who had received a kidney transplant 12 years earlier, due to polycystic kidney disease, currently with low doses of immunosuppression (ciclosporin 75mg/12h and mycophenolate mofetil 50mg/12h). She visited the emergency department owing to abdominal pain for the past 48h, located in the mesogastrium and associated with vomiting. Laboratory testing revealed a haemoglobin level of 6g/dl and no signs of gastrointestinal bleeding. An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was normal, and a lower gastrointestinal endoscopy showed multiple superficial ulcers with signs of bleeding in the terminal ileum and ascending colon. A biopsy reported positive immunostaining for CMV. A PCR for CMV was requested and more than 10,000 copies were obtained, and so intravenous treatment was started with ganciclovir and immunoglobulin. At 48h she had severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding that required transfusion of 6 packed red blood cell units. She underwent an arteriogram of both mesenteric arteries, which did not reveal the bleeding point. A colonoscopy showed that the previously detected ulcers had not improved and revealed a penetrating ulcer in the ileum with active bleeding, which was treated with endoscopic sclerosis. At 12h the patient had a new episode of severe gastrointestinal bleeding, and so she underwent a resection of the affected ileum and the caecum. The surgical specimen showed multiple superficial ulcers and an ulcer with a diameter of around 2cm that reached the serosa (Fig. 1A). The definitive diagnosis was ulcerative enteritis due to CMV (Fig. 1B). Her postoperative course was favourable and, currently, at 3 years from her signs and symptoms, she has had no recurrence of CMV infection.

(A) Intra-operative image of the resected specimen. An opening has been made in the resected loop of small intestine and the ulceration that is the source of the bleeding may be observed. B) Histology image with H&E 400×. Cytomegalic inclusions (arrows) in the interior of the mucus-depleted intestinal cells.

CMV infection represents one of the most common opportunistic infectious diseases after a kidney transplant, and leads to an increase in the recipient's morbidity and mortality. It affects 60–80% of patients, 25–50% of whom develop clinical disease.1,2 Symptomatic CMV infection in the gastrointestinal tract occurs in 5–10% of patients who receive kidney transplants, and may affect the patient from the oesophagus to the colon. Ulcers occur because CMV causes vasculitis in the gastrointestinal tract, which may cause gastrointestinal bleeding and even intestinal perforation.4 However, late disease due to CMV (after 6 months have passed since the transplant) is uncommon, especially if there is no increase in immunosuppressive treatment due to late acute rejection.4,5

Different studies, including some multi-centre studies, have shown that the use of mycophenolate mofetil decreases the incidence of episodes of acute rejection; however, it seems to increase the frequency and severity of CMV infection,3,6 as was observed in our patient. Cornelis et al.3 indicated that, although it does not bring about an increase in primary CMV infection, it does cause an increase in development of disease due to CMV. Our case was unique with respect to what has been reported by several authors owing to the aggressiveness of the intestinal involvement despite the low doses of immunosuppression and the antiviral treatment started.7–10

The treatment of choice in these cases of late CMV infection is the use of specific antiviral agents, which in the majority of cases is effective.1,8 Colonoscopy is a good diagnostic and therapeutic method in patients in whom a bleeding point is located. In our case, the lesion was located properly, but the treatment was not effective. Therapy with embolization using interventionist radiology may be used in these cases of massive bleeding; however, a flow rate of 0.5 to 1ml/min is required to show bleeding, and this sometimes brings about a diagnostic problem owing to the intermittent nature of episodes of gastrointestinal bleeding, as occurred in our case. Surgery is reserved for cases in which all the above fails, and its major problem is locating the bleeding point, as a segmental resection, as in our case, is not the same as a massive intestinal resection. The mortality rate of surgery ranges between 10% and 55%.1 In our case, a segmental resection fostered the patient's good clinical course.

In conclusion, late intestinal CMV infection should be suspected in transplant recipients treated with mycophenolate who start with latent gastrointestinal signs and symptoms. Surgery is the last therapeutic step, and locating the bleeding point is essential for managing signs and symptoms.

Please cite this article as: Ríos A, Ruiz J, Rodríguez JM, Parrilla P. Hemorragia digestiva baja masiva por citomegalovirus en un trasplantado renal con bajas dosis de inmunosupresión. Nefrologia. 2016;36:454–455.