La afectación renal asociada a linfoma es un fenómeno conocido pero frecuentemente no caracterizado debido a la baja frecuencia con que se realizan biopsias en estos pacientes. Varios patrones histológicos pueden coexistir y pasar desapercibidos sin un estudio histopatológico. La infiltración parenquimatosa renal por linfoma no es infrecuente, y se ha encontrado hasta en un 34% (post mortem) y 14% (pre mortem), aunque tiene una baja incidencia de manifestaciones clínicas. Existen diferentes patrones de lesión renal asociados a linfoma y destaca la asociación de enfermedad de cambios mínimos con linfoma de Hodgkin. La afectación renal asociada a paraproteínas sintetizadas por un linfoma linfoplasmocitario es una asociación excepcional pese a que existen un 20% de pacientes afectados por dichos linfomas que presentan crioglobulinemia. En la literatura se han publicado casos de enfermedad de cadenas ligeras, amiloidosis, glomerulonefritis inmunotactoide como causas de paraproteinemia, proteinuria e insuficiencia renal en pacientes con linfoma. Presentamos un caso de asociación entre paraproteinemia, glomerulonefritis membrano-proliferativa y la aparición clínicamente evidente de un linfoma linfoplasmocitario en ausencia de infección por virus de la hepatitis C. Esto demuestra la afectación polimorfa que pueden presentar los linfomas en el riñón y el valor de la nefropatología en el diagnóstico y pronóstico de las enfermedades hematológicas que cursan con paraproteinemia.

Kidney involvement associated to lymphoma is a known phenomenon but frequently not characterized due to the low frequency with which biopsies are realized in these patients. Several histological patterns can co-exist and happen unnoticed without a biopsy. Parenchyma infiltration in kidney for lymphoma has been found in 34% (post-mortem) and 14% (pre-mortem) and have low incident of clinical manifestations. Other patterns of renal injury are associated to lymphomaand minimal changes disease is especially related with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Renal lesions associated to paraprotein in lymphoplasmocitic lymphoma are an exceptional association, in spite of in 20% of them, appear cryoglobulinemia. There are a few cases reported in the literature with different histological patterns: light-chain disease, amyloidosis, and immuotactoid glomerulopathy related with kidney injury in patients with lymphoma. A 39-year-old male presented an association among paraproteinemia, membrano-proliferative glomerulonephritis no hepatitis C virus related and lymphoplasmocitic lymphoma with renal infiltration. This case emphasized the variety of renal lesions that lymphomas could trigger and the value of the nephropatology in the diagnosis and outcome of the hematologic diseases with paraproteinemia.

INTRODUCTION

Kidney involvement associated with lymphoma is a known phenomenon, but is not frequently characterised because of the low frequency of biopsies performed in these patients, in which several different histological patterns may coexist and go unnoticed in the absence of a histopathological analysis.1

Infiltration of the renal parenchyma by a lymphoma is not an uncommon phenomenon, and it has been observed in up to 34% of cases in post mortem studies. However, only 14% of these were actually diagnosed before death, due to the low incidence of clinical manifestations and/or renal failure observed in these patients. Additionally, several different studies have shown that lymphomatous infiltration of the kidney is associated with a poor prognosis from a haematological point of view.2

However, there are other patterns of renal damage associated with lymphomas, such as the association of minimal-change disease with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, in which this glomerulopathy accounts for 40% of all cases with renal disease.3 On the contrary, the association of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis and lymphoma is much less frequent than the rate published for this glomerular disease with regard to solid organ tumours.1 Renal damage associated with paraproteins synthesised by lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma is a rare occurrence, despite the fact that approximately 20% of lymphoplasmacytic lymphomas progress with cryoglobulinemia and the almost always present IgM kappa monoclonal gammopathy.4 Cases have been described in the medical literature of light-chain disease,5 amyloidosis,5 and immunotactoid glomerulonephritis6 as causes of proteinuria and renal failure in patients with lymphoma. Here, we present, in chronological order, an example of the association between the appearance of paraproteinemia, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, and a clinically evident lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL) in the absence of infection by hepatitis C virus (HCV), which shows the polymorphic manifestations that lymphomas can take in the kidney, as well as the value of nephropathology in the diagnosis and prognosis of a haematological disease that presents with paraproteinemia.

CLINICAL CASE

Our patient was a 39-year-old male, with no toxic habits, allergic to acetyl-salicylic acid (ASA) and diclofenac. He initially sought treatment for swelling of the soft tissues associated with palpable purpura in the lower extremities in April 2001. We performed an immunological analysis that revealed positive cryoglobulinemia with a cryocrit of 9.2% (monoclonal IgM kappa and IgG component). Serology tests for hepatotropic virus and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were negative, and the antiphospholipid antibody test was also negative.

A physical examination revealed the presence of palpable purpura in the lower extremities; the rest of the exam was normal. He underwent thoraco-abdominal computerised tomography (CT) that did not show any evidence of adenopathies or visceromegalies. Diagnosed with cutaneous vasculitis, the patient was prescribed prednisone at 1mg/kg/day, with favourable initial evolution and the disappearance of lesions.

One year after the first medical visit, the patient complained of paraesthesia in the lower extremities, again associated with petechiae in the same area, and on this occasion the patient also had nephritic syndrome. The laboratory analysis resulted in: hypocomplementemia, cryocrit of 17%, and a proteinogram with a weak anomalous band in the gamma zone. The serum immunoelectrophoresis showed restricted mobility IgM kappa component (there was no evidence of monoclonality in the urine). Renal function included a creatinine level of 1.2mg/dl, sediments with +++ red blood cells, and proteinuria at 2.8g/day.

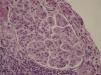

A kidney biopsy confirmed the presence of glomerulonephritis with a mesangiocapillary pattern (Figure 1). We added azathioprine to the treatment regimen, maintaining renal function and proteinuria close to 1g/day.

After 6 months of follow-up, a control laboratory test revealed an immunophenotype that was compatible with LPL in a peripheral blood sample. This finding was later confirmed through a bone marrow aspiration that revealed medullary infiltration from small-type B-cell chronic lymphoproliferative syndrome, compatible with quiescent LPL, and so at this point the patient was no longer given chemotherapy.

One year later, the patient developed persistent proteinuria (4.7g/24h), for which we took another renal biopsy that confirmed the presence of cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis, and also showed lymphocyte infiltration compatible with low-grade B-cell lymphoma (Figure 2). Given the renal involvement of the lymphoma, we decided to start treatment with subcutaneous rituximab at 375mg/m2x4 and a cycle of plasma exchange.

Two years after receiving anti-CD20 treatment, the patient currently has lymphoproliferative syndrome that is in remission, and the renal damage continues in the form of residual proteinuria (4g/day), with conserved renal function (Cr: 0.8mg/dl, GFR: 100ml/min) and treatment with dual blockade of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

In addition to the peculiar clinical progression of this patient, in which mixed cryoglobulinemia was the first manifestation of LPL, this case exemplifies the rare association between lymphoma and cryoglobulin-associated glomerulonephritis. The absence of HCV stands out, since it is common in patients with the combination of cryoglobulinemia, glomerular disease, and lymphoproliferative syndrome.

The majority of cases of LPL show up in serum samples with IgM paraprotein, and 20% of this paraprotein may be cryoglobulins that can result in auto-immune phenomena, such as in this case, or a protein that could cause a coagulopathy due to the bond of IgM to coagulation factors, platelets, and fibrin.7

The best therapeutic option in this clinical context is anti-lymphoproliferative treatment in order to slow the growth of the tumour mass, and elimination of the paraprotein that was secreted by the lymphoma using plasma exchange (PE).

In a multi-centre retrospective study of 33 cases of mixed cryoglobulinemia that were initially classified as idiopathic, the cause of the condition was established in 20 patients. Following a mean follow-up period of 67.2 months, the results were 14 cases of autoimmune disease, two cases secondary to infections not related to HCV, and four patients with lymphoma. This study, as in our case, demonstrated the usefulness of long-term follow-up in patients with idiopathic cryoglobulinemia, including the evaluation of renal function and urine sediment.8

Another study described in the medical literature examined 18 patients with increased serum creatinine levels and, in many cases, proteinuria. The renal biopsy puncture showed direct damage to the kidney from several neoplasias, including CLL/small lymphocytic lymphoma (n=7), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (n=6), multiple myeloma (n=4), and B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma (n=1).

In 10 cases (55%), there was a coexisting glomerular pathology: five had glomerulonephritis with membranoproliferative patterns (n=4) and membranous nephropathy (n=1), characterised by immune complex deposits; two had immunoglobulin deposit with a monoclonal component of amyloid lambda light chains (n=1), and light-chain deposition disease (n=1); two had minimal change disease, and one patient had focal pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis. Additionally, one biopsy revealed diabetic nephropathy, and three cases had non-specific ischaemic changes. In the four remaining cases there were no significant glomerular changes. In 11 cases (61%), the diagnosis of lymphoproliferative syndrome was made after renal biopsy.9

This case highlights the usefulness of renal biopsies as a diagnostic tool for: 1) better characterisation of the different stages of lymphomas with renal manifestations, since they can be polymorphic, as in our patient, who progressed from nephritic syndrome to nephrotic syndrome, and 2) as a biological substrate upon which to suggest an early treatment regimen for this type of haematological pathology.

CONCLUSIONS

The kidneys can be a target organ in patients with LPL. The early indication for renal biopsy in patients with renal damage and LPL will allow us to determine other rare patterns of renal damage that are produced in patients with this type of lymphoma, and thus avoid under-registering the association between nephropathy and LPL.

Additionally, renal biopsies in these patients will facilitate a rapid diagnosis and early start of chemotherapy, which is a key factor in the renal recovery of patients with oncohaematological diseases.

Based on these conclusions, the relevance of analysing renal function and the urine sediment in the follow-up of patients with lymphoma is highlighted, as well as cooperation with pathologists, allowing for a clinical-pathological partnership throughout the evolution of this disease.

Figure 1. Proliferative glomerulonephritis with a mesangiocapillary pattern

Figure 2. A: dense lymphocyte infiltration by B-lymphocytes compatible with B-cell lymphoma (haematoxylin-eosin). B: immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, and the figure shows the positive CD20 staining

Figure 3. Schematic of the clinical progression (follow-up over 10 years) from the start of cutaneous vasculitis from cryoglobulins to the diagnosis and treatment of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma