To the Editor,

Acute renal failure associated with intratubular crystal precipitation is a common cause of renal injury which may occur in the context of a wide variety of clinical situations. The most common are those associated with uric acid nephropathy and with intravenous acyclovir, sulphonamides, methotrexate, and indinavir treatment. Most patients affected by this type of renal disease have a variety of predisposing risk factors, notable among which are effective intravascular volume depletion and previous chronic renal failure.1

Ingestion of ethylene glycol and, exceptionally, the administration of ascorbic acid at high doses can cause hypercalcaemia and acute renal failure due to deposition of oxalate crystals.2 However, enteric hyperoxaluria is another potential cause of kidney stones and interstitial nephritis in patients with short bowel syndrome or other causes of fat malabsorption in patients without colectomy.3,4

We report the case of a 59-year old patient who underwent surgery for a Bismuth type IIIB hilar cholangiocarcinoma in September 2009. There were a number of complications after the intervention: ischaemic necrosis of the right hepatic lobe anterior segments, a biliary fistula and abscesses in the surgical site. The patient was therefore eventually discharged wearing a drain in the surgical site. In January 2010, the patient was admitted due to acute renal failure with serum creatinine of 9.6mg/dl, vomiting and increased cardiac output due to drainage. Urine sodium was 34meq/l. Additional tests also highlighted the presence of a proteinuria of 0.6g/24h and urine sediment with 10 red cells per field without leukocyturia. The patient had a beta-2-microglobulin level of 548.72μg/g and NAG of 9U/l in the urine. The renal function continued to deteriorate despite volume replacement and a renal biopsy was performed to investigate the origin of the acute renal failure.

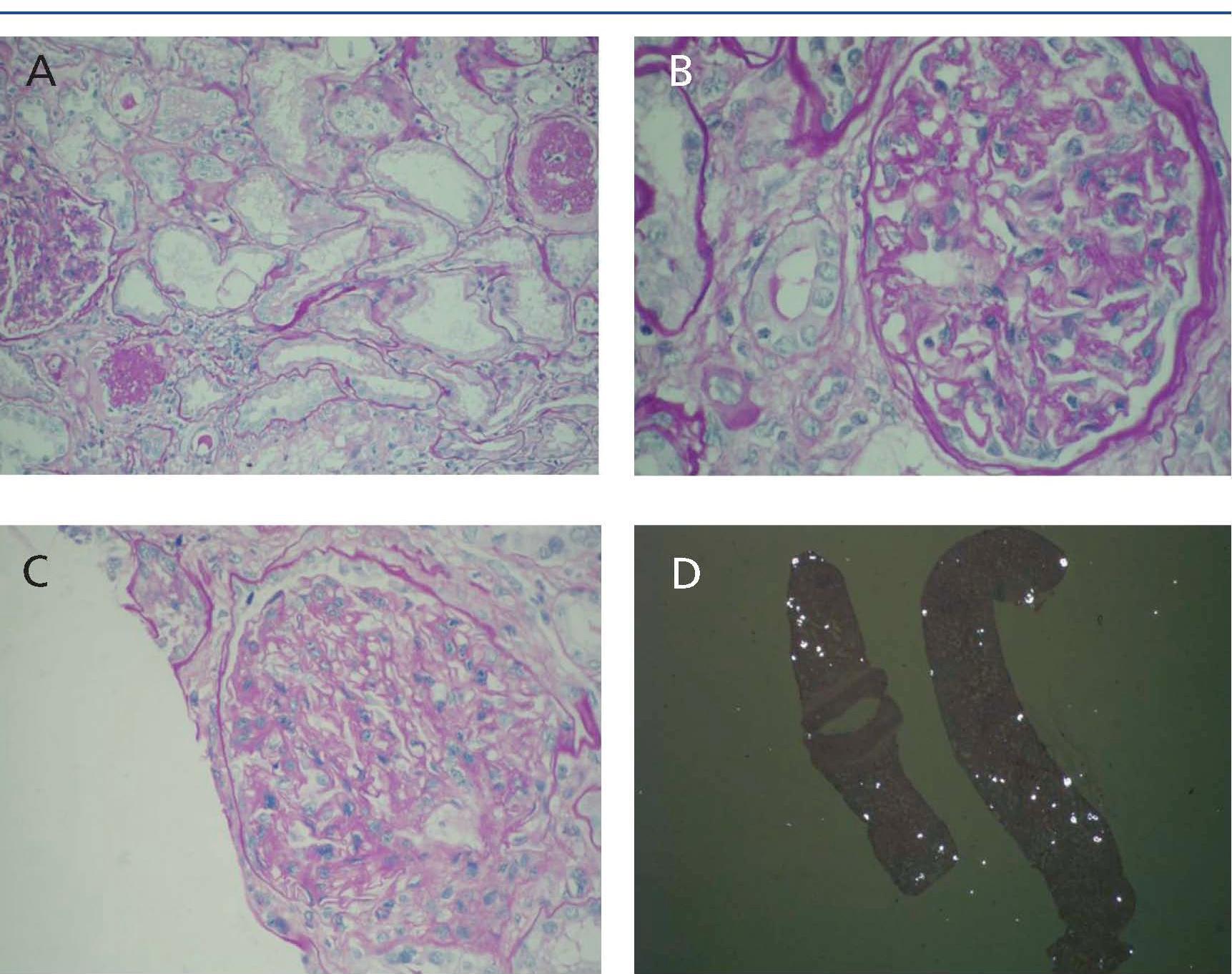

The renal biopsy showed varying degrees of shrinkage with fibrous thickening of the capsule in some glomeruli. Diffuse fibrosis was observed in the interstitial area, with focal tubular atrophy affecting approximately 25% of the parenchyma. Predominantly lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate was detected in various areas, with occasional presence of eosinophils. Some tubules had necrotic cylinders in the lumen. The lumen of many tubules was occupied by birefringent crystals consistent with oxalate (Figure 1).

The oxalate in urine was 47.70mg/24h (up to 40mg/24h with normal renal function). After hydration, correction of acidosis, treatment with calcium carbonate and low oxalate diet, the patient presented a successful evolution, with a progressive decline in serum creatinine to 2mg/dl prior to discharge.

Under normal conditions, the daily load of endogenous and exogenous oxalate is completely excreted by the kidneys. When renal function is altered, renal and extrarenal deposits of oxalate begin to appear, which is known as systemic oxalosis. When there is a high oxalate load, hyperoxaluria is produced, increasing the risk of nephrolithiasis and nephrocalcinosis. In addition, acute renal failure may be triggered in patient with a precipitating factor, such as dehydration and/or metabolic acidosis.

Hyperoxaluria is defined as the presence of urinary oxalate values greater than 40mg/day. It is frequently observed in patients with fat malabsorption due to digestive hyperabsorption of oxalate, unlike primary hyperoxaluria due to enzyme deficiencies associated with a hyperproduction of oxalate in the liver.5

The patient in question presented an enteric hyperoxaluria in relation to malabsorption of fats. The main mechanism involved is the binding of calcium in the intestine by fatty acids, which decreases the calcium oxalate in the digestive tract and increases the ionised oxalic acid absorbed in the intestine. These patients may benefit from conservative treatment based on reducing oxalate and fat in the diet, the administration of calcium carbonate as an oxalate binder, and an increased intake of fluids and administration of bases, such as sodium citrate, in order to increase urinary calcium oxalate solubility. Likewise, it has yet to be confirmed if recolonisation with Oxalobacter formigenes also reduces urinary oxalate excretion.6

In conclusion, calcium oxalate deposition associated with enteric hyperoxaluria is a rare cause of acute renal failure in the native and transplanted kidney.5,7,8 Patients with fat malabsorption are at high risk and should be identified and treated early to prevent loss of kidney function. If parenchymal acute renal failure is seen in a patient with fat malabsorption, urinary oxalate excretion should be measured, deterioration of the acid-base balance reversed and early hydration provided.

Figure 1. Renal biopsy. 1A) Diffuse interstitial fibrosis with focal tubular atrophy and interstitial foci of inflammatory infiltrate; 1B) Glomerulus with fibrous thickening of the capsule; 1C) Expansion and mesangial sclerosis; 1D) Tubules with lumen occupied by b