Improved outcome and longer life expectancy in patients with cystinosis and the intrinsic complexity of the disease, underline the need for a guided transition of patients from pediatric to adult care. The process aims to guarantee the continuum of care and enable the empowerment of patients from guardian to self-care.

MethodsBibliography review, expert opinion and anonymous surveys of patients, relatives and patient advocacy groups.

ResultsA new plan to support and coordinate the transition of cystinotic patients providing specific proposals for a variety of medical fields and improved treatment adherence. Nephrologists play a key role in the transition since most cystinotic patients have severe chronic kidney disease and require kidney transplantation before adulthood.

ConclusionWe present a proposal providing recommendations and a chronogram to aid the transition of adolescents and young adults with cystinosis in our area.

El aumento de la supervivencia de los pacientes con cistinosis y la propia complejidad de la enfermedad explican la necesidad de implementar un proceso de transición guiada desde la medicina pediátrica hasta la del adulto, que permita garantizar el continuum asistencial y posibilite el empoderamiento del paciente desde el cuidado tutelado al autocuidado.

MétodosRevisión bibliográfica, opinión de expertos, encuestas anónimas a pacientes, familiares y asociaciones.

ResultadosElaboración de un documento de transición coordinada, con propuestas concretas por especialidades y de mejora de la adherencia terapéutica y del autocuidado del paciente. El nefrólogo desempeña un papel clave en la transición en la cistinosis debido a la afectación renal que domina la patología y porque la mayoría de los pacientes han recibido un trasplante renal antes de la edad adulta.

ConclusiónSe presenta un documento que establece unas recomendaciones y un cronograma para guiar la transición de los adolescentes y adultos jóvenes con cistinosis en nuestro ámbito.

Medical advances have transformed cystinosis from a historically fatal childhood disease1,2 into a chronic adult disease3 with longer life expectancy.4 Nevertheless, the transfer of young patients to adult units has led to interruptions in their medical care,5 inadequate patient follow-up and worsening of the disease.6 The acknowledgment of several factors underlying this situation illustrates the need to implement specific programs for the transition of adolescent cystinosis patients to adult care.7,8

Cystinosis is a rare (RD),1 severe systemic disease caused by mutations in the CTNS gene (17p13) that alter cystinosin synthesis, resulting in the accumulation of lysosomal cystine crystals in all body cells.2,9,10 With an incidence of 1/100,000–200,000 newborns,1 cystinosis is characterized by early renal involvement that evolves to kidney failure with corneal crystal deposits and other progressive extra-renal manifestations.11 Control of this disease requires a strict and complex therapeutic regimen1,5,6 together with rigorous periodic monitoring of cystine concentrations in granulocytes throughout the patient's life.9,11,12

Cystinosis use to be an exclusively pediatric disease and patients would die prematurely from kidney failure before the end of the first decade of life.1,4 The availability of specific treatment with cysteamine2,13 and the success of pediatric kidney transplant (KTx) programs14,15 now prolong patient survival to over 50 years.4 Consequently, a growing number of adolescents and young adults with cystinosis are being admitted to adult units where the number of experts in this rare disease is extremely low.16 Furthermore, since unexpected clinical worsening has been observed in many cases after these transfers, it is a matter of concern that the clinical progress achieved in pediatric patients tends to decline in adulthood. Numerous risk factors converge to explain this situation such as: (a) the inherent difficulty in caring for an adolescent/young adult with a chronic disease who has usually received a kidney transplant5,6 and thus has a high risk of graft loss7; (b) the lack of experience and familiarity of adult patient especialists with this RD4; (c) extra-renal involvement progression16; (d) non-compliance with treatment, which is common in this specific patient population,5,17 and (e) the lack of experts close to the patient's place of residence.8 Thus, various healthcare strategies for RD have been proposed including referrals to centers of expertise, among others.18,19

Cystinosis represents the paradigm of RD that requires a guided transition to adult medical care. Owing to the specific characteristics of the disease3–5 patients face unique challenges during the transfer process to adult units,6,7,20 which usually follows a generalized pattern.21 In Spain, there are currently around 60 patients with cystinosis, 30% of whom are children, 17% adolescents and the rest are adults who, in some cases, continue to receive treatment in pediatric units. Thus, it is imperative to implement healthcare strategies to educate patients about their disease, promote self-care and organization, and support their transition to adult care.17 This proposal is intended as a useful tool for healthcare professionals to facilitate the planning of a coordinated transition for cystinosis patients in our healthcare setting.

MethodologyThis work is the result of different methodologic strategies implemented by the T-CiS.bcn group: (1) a literature search on PubMed using the following key words: “cystinosis”, “transition”, “adolescent”, “renal transplant” and “adherence”; (2) a survey carried out on members of the T-CiS.bcn group themselves to identify the needs and challenges of transition in the healthcare setting and favor the implementation of improvement strategies; and (3) anonymous feedback from cystinosis patients and their relatives of the Spanish Cystinosis Group (www.grupocistinosis.org), represented by the Spanish Association for Information and Research on Genetic Renal Disease (AIRG-E; www.airg-e.org).

Theoretical framework: healthcare strategies for rare diseases in the European UnionThe European Union defines a disease as rare when it affects no more than 5 in 10,000 individuals. There are approximately 8000 different RD, affecting up to 8% of the population. The majority suffer from ultra-rare diseases, i.e. those with a frequency of ≤1 in 100,000, which render these patients particularly vulnerable and isolated.21 The European Commission has defined and adopted several preventive, diagnostic and treatment strategies for RD, aimed at improving healthcare access and equity among affected patients and ultimately improving their quality of life. The healthcare policies of each EU member state are based on the following Council Recommendations22:

- (1)

Produce and adopt RD action plans and strategies based on the healthcare systems and social services of each country.

- (2)

Define, encode and produce RD registers.

- (3)

Foster research on RD.

- (4)

Identify centers of expertise (CE), create European RD reference networks based on multidisciplinary healthcare, and to divulgue knowledge.

- (5)

Centralize RD experience: good clinical practise guidelines and training programs on the diagnosis and treatment of RD; facilitate access to orphan drugs and clinico-therapeutic assessment reports.

- (6)

Promote the empowerment of patient associations (PA) through their involvement in developing healthcare policies and providing access to up-to-date information on RD.

- (7)

Ensure sustainability i.e. the long-term maintenance of information, research and healthcare structures.

In order to comply with recommendation N°4, the European Union Committee of Experts on Rare Diseases (EUCERD) defined the following criteria for the designation of a CE21:

- (1)

Volume of relevant healthcare activity and capacity to offer quality services.

- (2)

Capacity to provide expert advice and clinical diagnoses, and produce and implement clinical protocols and quality control.

- (3)

Multi-disciplinary healthcare.

- (4)

High level of expertise and experience documented through publications, grants and training courses.

- (5)

Concerted contribution to research.

- (6)

Involvement in epidemiologic surveillance: patient registries.

- (7)

Close links and collaboration with other centers of excellence. Involvement in research networks.

- (8)

Capacity to interact with Patient Associations (PA).

- (9)

Advisory service.

- (10)

Proven capacity for clinical patient follow-up.

Spain approved the Rare Diseases Strategy of the National Health System in June 2009.23 Likewise, the Spanish Federation for Rare Diseases (FEDER; www.enfermedades-raras.org) acts on behalf of the 3 million individuals with rare diseases in Spain.

What is transition?Transition is a planned, anticipated and coordinated process that aims to prepare and transfer the pediatric patient from guardian-care to an adult unit where they will become responsible for their own self-care.24 The transition phase will be gradual, progressive and adapted to the patient's individual maturity, which often fails to match the approved age at transfer. This process must ensure that the patient receives adequate and continued care during the changeover.7,25

Why is transition important?The lack of organizational strategies in the transition phase has often led to unpredictable worsening of the patient's health.24,25 Historically, very severe complications were observed in young patients with chronic diseases shortly after being transferred to adult units.26 This was especially evident in KTx cases, with graft loss being particularly common.8 In fact, adolescents and young adults who have received a KTx are known to be the group with the worst prognosis,27 and it is generally agreed that adolescents are incapable of undergoing the transition to adult care alone with guaranteed success. When faced with the temptation to blame the patient for this situation, it is important to consider that the healthcare system does not cater to the needs and specific characteristics of this population,26 where dissociation between the patient's chronological age and physical/psychologic maturity is common (development is not usually complete until the patient has reached 25 years of age). Similarly, many patients present some form of disability, which impedes their full autonomy.7,28

Characteristics of cystinosisIn the case of adolescent cystinosis patients, the transfer to adult specialists is even more difficult given the characteristics of the disease, which is systemic and progressive.1,3 This explains the great impact it has on personal and physical development,5,16,19,20 which is often associated with significant dependence and impairment.3,29–32 It should be emphasized that patients reach adult age because they have had personalized care and multidisciplinary attention during their childhood which must be continued into adulthood.17 The need for greater medical attention compared to other patients20,25 explains why the transition of adolescents with cystinosis represents a major challenge not only for the patients themselves but also for their families and the health professionals involved in their care.18,19 The characteristics of adolescent cystinosis patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are described below1,3,5,16,29–33:

- (1)

Disharmonic pubertal delay:

- -

Physical development delayed at least 2–3 years.

- -

Advanced emotional maturity for age in some areas (skills acquired due to the illness) and developmental delay in others.

- -

Incomplete brain development (estimated to end at approximately 25 years of age).

- -

- (2)

Progressive and systemic disease involvement (short stature, joint deformities, hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus, infertility, ocular involvement, cognitive and central nervous system disorders, distal myopathy, cardiovascular involvement).

- (3)

High dependency on complex medical treatment and hospital care.

- (4)

Problems with treatment adherence: polydrug use, high number of doses, adverse and transplant-specific effects.

- (5)

Difficulty in accepting that they are suffering from a lifelong illness, with severe kidney disease and disability. Active awareness-raising process.

- (6)

Feeling isolated and excluded from their peer group.

- (7)

Psychologic exhaustion due to the impact of the disease.

- (8)

Difficulties at school and in learning: academic delay and problems in social relationships, with bullying being common.

The transition process must be personalized and carried out in a gradual, step-by-step manner. The ideal time should be in keeping with the patient's individual maturity and their willingness to make the change7,8,20:

| When? |

| The changeover should only take place after a transition period dedicated to preparing the adolescent/young adult and receiving unit by providing the information required for treating the disease. |

| Planning: to start the process in preadolescence (12–14 years). |

| At a time of clinical and emotional stability. |

| How? |

| Personalized for each patient. |

| Gradual. |

| Consensus with the patient and family, and in agreement with the pediatric and adult healthcare teams. |

| After completion of compulsory education. |

| Gradually provide the patient with information. |

| Involve the patient's family and close friends for support. |

| Introduce the patient to the new medical team prior to the changeover at an informal visit. |

| Process supervised by “transition leaders” from the pediatric and adult units. |

| Have a predefined transition plan. |

| Identify the case manager/process coordinator. |

| Have the support of patient groups. |

| Take into account the treatment plans of the different medical specialities. |

| Provide the patient with support tools for self-management. |

| Take economic factors into account. |

The purpose of the transition plan is to oversee the patient's transfer following an established, continuous, uninterrupted therapeutic plan in an efficient and safe manner. In general, there are three chronologic stages: preadolescence (12–15 years), adolescence (16–18 years) and young adulthood (19–25 years) which correspond to the following respective phases: (1) creation and commencement of the transition plan; (2) educating the patient on self-care and self-responsibility, and (3) the transfer itself25 (Table 1).

Patient competencies and skills required for transition

| Stages | Preadolescent 12–15 years old | Adolescent 16–18 years old | Young adult 19–25 years old |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planning/introduction to the transition | Patient education | Transfer | |

| Disease | Know what he/she is suffering from and can briefly explain what cystinosis entails | Be able to explain the disease in greater detail, describing multi-systemic involvement | Understand the disease in depth, as well as his/her potential, multi-systemic involvement and complications |

| Recognize the extent of individual involvement | Recognize symptoms | ||

| Medication | Know the names of drugs, daily dose and schedule | Understand drugs in depth: indication, preparation, storage, side effects, risk of autonomy, drug interactions and an introduction to pharmacy circuits | Autonomy in the preparation and administration of medication, with minimum supervision |

| Participate in the preparation and administration of medication, with the supervision of a carer | Autonomy in the preparation and administration of medication, with the supervision of a carer | Autonomy in pharmacy circuits | |

| Understand the benefits of correct administration and the risks of non-adherence | Understand the benefits of correct administration and the risks of non-adherence in depth | Full responsibility for good treatment compliance | |

| Lifestyle habits and prevention | Start to understand health lifestyle habits (diet, physical exercise), high-risk behavior and sexuality | Understand and implement healthy lifestyle habits. Taught about high-risk behavior (drugs and alcohol), sexually-transmitted diseases and unwanted pregnancy | Fully understand and implement healthy lifestyle habits. Lack of high-risk behavior, knowledge of sexual and reproductive health |

| Relationship with the care team | Know the reference pediatric care team | Initiate contact with the adult team (sessions, workshops, associations, mentors) | Know the reference adult care team, the different specialists and the different levels of care involved in the process (social worker, primary care, etc.) |

| Start to get involved at medical appointments and initiating communications with the care team | Proactive attitude towards the care team, and able to express doubts and ask questions | Autonomy in communications with the care team |

Adapted from Cooley et al.25

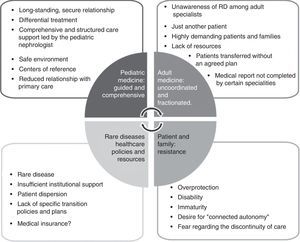

Identifying barriers is a fundamental step in recognising the patient's strengths and environment, and in improving the coordination and commitment of all parties involved. Child patients are seen by the pediatric nephrologist who focuses his/her attention on systemic involvement.5,6,18 This coordinated guardian care in pediatrics changes completely when the patient is transferred to adult care, where they are often seen by separate professionals primarily focused on their own speciality.19 The result is “fragmented care”, with negative repercussions on healthcare quality and continuity. This is seen by patients as a step backwards in terms of the care they are receiving and generates a loss of confidence in the medical team and resistance to change.18 This scenario is further exacerbated by the lack of resources set aside for RD. The result of this situation is reflected in Fig. 1, which presents the barriers to transition in cystinosis, some of which are also observed in many other RD.

How is transition seen by each of the agents involved?Through surveys conducted on patients and family members, information has been obtained on the impact of the disease along with attitudes towards transition.17,33–36

- (a)

Physical impact: patients feel different, above all because of their short stature and the effects of the disease and treatment.

- (b)

Psychologic impact: on personal relationships and in terms of their autonomy and social life. They are dependent on their family for care and the disease hinders their personal development. Conflicting feelings of overprotection and gratitude to those around them. Fear of rejection. Frequent discrimination at school and in the workplace. More depression and anxiety than in other chronic diseases.37

- (c)

Development of positive strategies and attitudes: adapting to the disease, fostering a healthy lifestyle, desire for personal growth and an appreciation of life.

Fig. 2 summarizes the attitudes and perceptions of cystinosis patients and the T-CiS.bcn group with regard to transition.

What are the requirements for transition in cystinosis?Main agentsIn cystinosis, as with other chronic RD, the transition process requires the active and integrated involvement of different parties, with the patient being both the main agent and the core around which the entire care process revolves.24,34 Given that the disease is progressive, new transition agents become incorporated over time: the hospital team, the family, patient associations, the case manager and the adult care and primary care teams.

The transition team comprises the pediatric nephrology group, adult nephrology—primarily the transplant team—and other non-nephrology specialists i.e. ophthalmologist, endocrinologist, neurologist, gastroenterologist, etc. involved in the patient's care according to extra-renal involvement. Likewise, nursing professionals specialised in transition must also participate in the process along with dietitians, psychologists, social workers and pharmacy specialists.

The case manager constitutes one of the mainstays of transition.9,38 The role of this professional, who is usually from a specialist nursing background (transplants, RD, etc.), has been created to facilitate coordination among different specialities within the same hospital, different hospitals and other levels of care. The case manager acts as a link between the different healthcare specialists, the patient and his/her family to ensure appropriate treatment coordination and guided emotional support during the transition. He/she must form part of both the pediatric and adult care teams to optimize the multidisciplinary effort and guarantee the continuum of the patient's care and follow-up in an efficient and lively manner.7,24,25

Some successful transition experiences featured the participation of so-called “transition leaders”, psychologists and/or social workers, and even young adult patients. Their role is to establish links between the medical team and patients, help them fit into the health care unit, build their self-esteem and trust in the new care team and provide the necessary support to overcome the difficulties inherent in having a chronic disease at a difficult stage such as adolescence.7,8

In addition to transitions between hospital teams at the same site or different connected hospitals, it is imperative in RD such as cystinosis to construct a working network to ensure good communication between CE and the patient's local follow-up units. As such, activities will be overseen by the case manager from the CE, thereby avoiding any unnecessary displacements of the patient and his/her family. This network approach will not only benefit the patient, but also the healthcare system, since the information shared will improve understanding of cystinosis across various levels of care and, as a result, improve the diagnosis and clinical follow-up of patients.

Although cystinosis patients are primarily cared for in a hospital setting, by the time they reach adulthood, primary care teams gradually take on their support, enlisting them in chronic disease management programs with benefits pertaining to medical prescriptions, home-based care, healthcare transportation, social welfare and disability support, among others.39

PA play a highly significant role in the care of RD patients, and share a common objective20 which is to pool opinions and ensure patient representation before health and government institutions and demand health care directed at the specific priority needs of cystinosis. Moreover, and no less importantly, PA spring from the need for companionship, support and closeness of families faced with the diagnosis and facilitating links to other patients and families by providing relevant information, health-related education and, to some extent, promoting research on cystinosis. There are various examples of how PA involvement benefits care regimens.38

Which physician should coordinate transitions in cystinosis?Pediatric and adult nephrology departments should be in charge of planning, organizing, implementing and monitoring the transition and transfer of adolescents and young adults with cystinosis.19,40 The kidney is well known to be the first organ affected by cystinosis, and this determines the morbidity and prognosis of the patient. The majority of patients progress prematurely to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) while still in chilhood,4,16 due in part to the fact that treatment with cysteamine does not achieve full renal remission.4 It is very rare for any form of extra-renal involvement in cystinosis to produce greater morbidity than kidney damage.1,5,6 For this reason, the nephrologist should be responsible for coordinating the transition given that he/she is in charge of the most severe disease during the process.41,42

Over 80% of cystinosis patients transferred to adult units have received a KTx, so are usually referred to nephrologists caring for kidney transplant patients.3,35 A handful of patients will arrive at the adult unit on dialysis, or might present symptoms of progressive CKD, with therapeutic requirements typical of the disease.19

Adult nephrologists are not usually familiar with cystinosis, which is understandable given the low prevalence of the disease. Cystinosis represents approximately 0.5% of the causes of CKD, and only a 0.1% of all patients over the age of 20 on renal replacement therapy.4,15 Thus, adequate communication and a positive attitude between pediatric and adult units are fundamental when planning the transition.

Transition plan or program in nephrologyThe success of the transition process lies in the generation and implementation of a transition plan that takes into account the following key components36:

- -

Appropriate age: flexible, based on the patient's health status, personal/physical development and degree of autonomy and whether the adult unit is ready to receive the patient.

- -

Preparation period: designed to provide the patient with the necessary skills for self-care, understanding of the disease and how to gradually become independent of their parents or carers.

- -

Coordinated process: between the pediatric and adult teams. Geared towards incorporating the patient in the adult follow-up program led by the key member: the case manager.

- -

Receiving hospital: the cystinosis patient must be monitored in a hospital setting with a kidney transplant follow-up program.

- -

Reference adult nephrologist: with appropriate skills and interest in the disease, able to provide the patient with an environment of trust.

- -

Administrative structure: for managing the multidisciplinary follow-up.

- -

Primary Care: to reinforce interactions between the different levels of care.

- -

In-process quality control program through the different stages.

The treatment of cystinosis patients is closely linked to highly specialised hospital care. There is no single transition model and pediatric patients may be transferred from a variety of settings:

- 1.

A children's hospital within a general hospital where the patient is not usually required to change site, thus favoring the continuum of care.

- 2.

A children's hospital that must transfer its patients to another adult center. However, this center is usually within close proximity, with established collaboration, thereby facilitating interactions between the healthcare teams.

- 3.

A children's hospital which, regardless of its nature, transfers patients to another referral center in a geographical area far from the patient's place of residence. This context poses the greatest difficulties, thereby reinforcing the need for a set transition plan.

The interests of the patient and their family and other personal factors will be assessed in all cases and at all times

- (a)

Circuit:

- (1)

Advise the patient who is reaching transition age and implement the protocol on an individual basis (follow-up visits with the case manager to reinforce the healthcare instruction).

- (2)

Apply selection criteria for the center of reference based on: the patient's place of residence, the patient's decision and the existence of a CE or nearby center of reference.

- (3)

Identify the most suitable adult nephrologist to receive the cystinosis patient according to the organization of the department and available resources.

- (4)

Establish communication between the case manager of the children's hospital and that of the receiving adult department.

- (5)

Draw up a specific transition plan from pediatric to adult nephrology. This should be specifically designed for the patient and hospital in question, and will include:

- -

Briefing (face-to-face, by telephone or via email) of the pediatric nephrologists, case manager and adult nephrologist to establish contact between the teams and consolidate a lasting relationship.

- -

Whenever possible, try to hold a joint meeting of both teams (final or penultimate visit prior to the transfer) to remove any barriers and facilitate the transition to external adult nephrology appointments. Should geographic barriers exist, foster a network approach.

- -

- (6)

Ensure that the pharmacy circuit adapts to the new circumstances and that the patient has enough of the specific medication required until admission to the receiving center.

- (7)

The actual transfer of the patient.

- (8)

Follow-up and monitoring of the transition to guarantee the continuum of care and detect any deviations from the protocol or unforeseen difficulties. The duration of this period will be agreed upon by both teams; it is recommended to last for the first year, which is the most critical period, or until a follow-up routine has been established at the adult center.

- (9)

Quality control of the transition model, including a registry of transferred patients and periodic updates of the transition protocol.

- (1)

- (b)

Essential documentation: medical report from the pediatric nephrologist and any other specialists involved in the patient's care. This record must include the following information:

- -

Clinical diagnosis (age at diagnosis, clinical characteristics, genetic diagnosis).

- -

Relevant personal history (including allergies and intolerances, vaccination schedule).

- -

Patient's childhood clinical history (on-going problems, resolved problems, serious renal and extra-renal complications).

- -

Pharmacologic treatment: up-to-date treatment plan, drug levels, specific therapeutic monitoring (intragranulocyte cystine levels) and report on treatment adherence.

- -

Final visit summary and a copy of the latest tests performed.

- -

Recommendations for clinical follow-up per speciality19:

- -

Up-to-date speciality-based appointment schedule.

- -

Appointment letter with comprehensive information for the patient and family (date and time of appointment, physician, contact details).

- -

Identification of the receiving specialist.

- -

Request for complementary tests for the next visit.

- -

- -

The T-CiS.bcn working group has proposed with the following transition recommendations for adolescents and young adults with cystinosis to complement those of the multidisciplinary follow-up recommendations for these patients in adult medicine, as indicated in the first part of the consensus document on comprehensive cystinosis care.19

Specific plans are provided herein for the most prevalent diseases in the transition phase: nephrologic, ophthalmologic, endocrinologic and neurologic (Tables 2–5), along with recommendations for improving treatment compliance (Table 6) and promoting patient self-care (Table 7).

Recommendations for the transition to adult nephrology

| Contact | Hospital Kidney Transplant Clinic |

| Optional: according to the patient's clinical status, consult nephrology or dialysis units | |

| Identify a suitable specialist to supervise follow-up. Assess whether there is a reference nephrologist for hereditary and/or rare kidney disease | |

| Referral criterion | Age: personalized criterion, but preferably at 18 years of age |

| Documentation for the receiving specialist | |

| 1. Information about the disease | Optional: recommendations for comprehensive cystinosis care from the T-CiS.bcn group19 |

| 2. Patient's medical record | |

| Detailed anamnesis | ||

|---|---|---|

| Anthropometric data (weight and height), blood pressure | ||

| Kidney transplant | Chronic dialysis | Chronic kidney disease |

| Background | ||

| Date | Start date | Stage of chronic kidney disease and rate of progression |

| Type of transplant (preventive or post-dialysis) | Type of dialysis (hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis) | Active status on the kidney transplant waiting list (or not) and why |

| Donor characteristics (alive or deceased, HLA, serologic tests) | Place of treatment (hospital, center, home) | Patient characteristics (HLA, serologic tests, other risks) |

| Receiver characteristics (HLA, serologic tests, other risks) | Vascular access (arteriovenous fistula, catheter), date and associated complications | Quantified diuresis, residual renal function and presence or absence of active Fanconi Syndrome |

| Surgical report (graft characteristics, initial transplant evolution) | Active status on the kidney transplant waiting list (or not) and why Receiver characteristics (HLA, serologic tests, other risks) | |

| Graft biopsy (protocol or elective, date and findings) | Dialysis prescription and efficacy (Kt/V) | |

| Anti-donor antibodies | Quantified residual diuresis, residual renal function and presence or absence of active Fanconi Syndrome | |

| Events | ||

| Episodes of rejection, acute renal failure, hypertension, cardiovascular involvement, dyslipidemia, diabetes, bone disease | Episodes of superimposed kidney failure, hypertension, cardiovascular involvement, dyslipidemia, diabetes, bone disease | Episodes of superimposed kidney failure, hypertension, cardiovascular involvement, dyslipidemia, diabetes, bone disease |

| Treatment plan | ||

| Immunosuppression regimen: | Secondary and therapeutic effects of the prescribed drugs | Secondary and therapeutic effects of the prescribed drugs |

| –Initial | Specific cysteamine therapy and intragranulocyte cystine levels | Specific cysteamine therapy and intragranulocyte cystine levels |

| –Significant changes and causes | Other treatments | Other treatments |

| –Current | Treatment adherence | Treatment adherence |

| –Maintenance immunosuppressant levels | ||

| –Side effects of immunosuppressants and other associated drugs | ||

| Specific cysteamine therapy and intragranulocyte cystine levels | ||

| Other treatments | ||

| Treatment adherence | ||

| Additional investigations |

| Latest blood test |

| Kidney ultrasound scan |

| Ocular fundus examination |

| Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring |

| Echocardiogram |

| Extra-renal involvement of cystinosis |

| Coordinated care with other specialists |

| Psychosocial assessment |

| Incapacity and disability |

| Education/labor autonomy |

| Family, social and legal status |

| 3. Monitoring patient follow-up |

| Apply the KDIGO guidelines (www.kdigo.org) or recommendations issued by scientific nephrology societies on the follow-up of kidney transplant, dialysis and pre-dialysis patients with chronic kidney disease |

| 4. Monitoring adherence to the topical ophthalmic treatment, systemic cysteamine therapy and other prescribed drugs |

Recommendations for the transition to adult ophthalmology

| Contact | Cornea and Ocular Surface Unit of the Hospital Ophthalmology Department |

| Identify a cornea specialist to supervise follow-up | |

| Referral criterion | Age: personalized criterion |

| Documentation for the receiving specialist | |

| 1. Information about the disease | Optional: Recommendations for comprehensive cystinosis care from the T-CiS.bcn group19 |

| 2. Patient's medical record | |

| 3. Patient monitoring | |

| In adolescence (16–18) | Tests every 6 months |

| In adults | Tests every year |

| 4. Recommendations for optimal periodic follow-up | |

| Slit lamp biomicroscopy | Assess the cornea and anterior segmenta |

| It is of interest to describe any corneal crystal distribution at each examination, specifying whether they are only deposited at the periphery or if their distribution is diffuse, and whether they are located in the epithelium, stroma and/or endothelium. This information will allow for better follow-up in the future | |

| Measure intraocular pressure | |

| Examination of the ocular fundus under mydriasis | |

| 5. Recommendations in exceptional circumstances | |

| Photopic and scotopic electroretinogram | If the patient mentions night vision problems or if the ocular fundus is altered |

| Ocular fundus examination 2–3 months after starting treatment with certain drugs (growth hormone, oral contraceptives, etc.) | If the patient is undergoing treatment with drugs that have a reported association with benign idiopathic intracranial hypertension and if they present headaches. |

| Ophthalmologic emergency | If the patient mentions a severe and/or acute loss of vision, given that these symptoms are not typical of cystinosis |

| 6. Topical ophthalmic treatment19 | Cysteamine saline solution 0.55%. Cysteamine viscous solution 0.55%. Up to 4 times a day. |

| One drop 10–12 times a day | |

| 7. Monitoring adherence to the topical ophthalmic treatment, systemic cysteamine therapy and other prescribed drugs | |

The presence of corneal cystine crystals is universal and is the main ocular target in cystinosis.

Taken from Ariceta et al.19

Recommendations for the transition to adult endocrinology

| Contact | Endocrinology Department |

| Identify a suitable specialist to supervise follow-up. Assess whether there is a reference endocrinologist for hereditary and/or rare diseases | |

| Referral criterion | |

| Age | Personalized criterion |

| Pubescent stage at transfer | Tanner IV or below, or a history of delayed puberty (onset of puberty: ♂>14 years old; ♀>12 years old) |

| If receiving treatment with: | Thyroxine, insulin, GH or testosterone |

| Analytical abnormalitites in follow-up endocrine parameters19: | T4L, TSH, glycemia, HbA1c, GH, IGF-1, testosterone, LH, FSH |

| Gestational desire | |

| Documentation for the receiving specialist | |

| 1. Information about the disease: | Optional: Recommendations for comprehensive cystinosis care from the T-CiS.bcn group19 |

| 2. Patient's medical record | |

| 2.1. Clinical data | |

| • Staturo-ponderal development | Weight, height and weight/height percentile at last visit (ideally a scanned copy of the patient's height and weight chart) and bone age |

| • Pubescent development | Tanner maturity stage upon transfer |

| • If the patient presents diabetes | Data relating to the study of chronic complications and other vascular risk factors |

| 2.2. Analytical data (latest value/date) | |

| • T4L, TSH | |

| • Glycemia, HbA1c | |

| • GH, IGF-1 | |

| • ±GH secretion test | |

| • Testosterone, LH, FSH | |

| 2.3. Hormone replacement therapy | |

| • (BV/BV date/treatment start date/preparation and dosage/recent dosage changes/functional tests) | |

| • Thyroxine | |

| • Insulin | |

| • GH | |

| • Testosterone | |

| 3. Monitoring adherence to the topical ophthalmic treatment, systemic cysteamine therapy and other prescribed drugs | |

BV: baseline value prior to the treatment.

Recommendations for the transition to adult neurology

| Contact | Neurology Department |

| Identify a suitable specialist to supervise follow-up. Assess whether there is a reference neurologist for hereditary and/or rare diseases | |

| Referral criterion | Age: personalized criterion |

| Documentation for the receiving specialist | |

| 1. Information about the disease: | Optional: Recommendations for comprehensive cystinosis care from the T-CiS.bcn group19 |

| 2. Patient's medical record | |

| Information regarding the presence of neurocognitive, behavioral or school performance problems | Almost 50% of children under the age of 18 present alterations in their overall cognitive performance, with repercussions on school performance. Problems with: attention, executive functions, language and memory have also been identified, as well as with perceptive, visuospatial and visuoconstructional functions and voluntary cognitive motor control. |

| Latest neuropsychologic explorations | Assess overall cognitive performance and report the presence (or absence) of anxiety, depression and behavioral alterations |

| Latest muscular strength assessment | Manual MRC and quantitative determinations of hand muscle strength by means of validated dynamometers |

| In the event that distal myopathy is present, its functional repercussion on the patient's daily activities will be provided | |

| Latest report on orofacial and deglutory motor function and respiratory function | Report episodes of bronchoaspiration or recurrent pneumonia |

| Latest neuroimaging tests | Report calcifications, brain volume loss and other anomalies |

| Quantify the degree of cerebral atrophy | |

| 3. Monitoring adherence to the topical ophthalmic treatment, systemic cysteamine therapy and other prescribed drugs | |

MRC: Medical Research Council scale.

Recommendations for improving treatment adherence in transition

| Therapeutic adherence assessment methods46,47 |

| 1. Direct methods |

| 1.1. Monitoring of intragranulocyte cystine levels (6h post-Cystagon® dosing)9,12 |

| • Good therapeutic control: <1nmol ½ cystine/mg protein |

| • In patients who do not receive treatment with cysteamine, levels are usually>1.5 |

| • This method may be influenced by individual factors such as drug absorption, extraction and sample shipment conditions19 |

| 1.2. Assessment of corneal cystine deposits |

| • Detail any corneal crystal distribution at each slit lamp examination, specifying whether they are only deposited at the periphery or if their distribution is diffuse, and whether they are located in the epithelium, stroma and/or endothelium. |

| 2. Indirect methods |

| 2.1. One-to-one interview with the patient (always assess adherence during the appointment) |

| 2.2. Adherence questionnaire |

| 2.3. Drug dispensing record of the Hospital Pharmacy Department |

| 2.4. Count the patient's leftover medication at each dispensation |

| 2.5. Use of electronic devices and specific computer applications to record administrations |

| Measures for improving therapeutic adherence40–42,44–49 |

| 1. Identify any risk factors affecting adherence and apply corrective measures whenever possible |

| Socioeconomic and patient-related factors |

| Disease-related factors |

| Treatment-related factors |

| Health organization barriers |

| 2. Promote the patient health education, the treatment benefits and the consequences of non-adherence |

| 3. Foster the support of those close to the patient, involving the family and patient associations |

| 4. Implement direct non-adherence detection measures |

| 5. Implement indirect non-adherence detection measures |

| 6. Implement direct treatment compliance support measures |

| Agree on treatment plans with the patient and review these at each appointment |

| Inform the patient of potential side effects of the treatment and about interventions to alleviate them |

| Simplify the treatment as much as possible |

| Plan and adapt the medication to the patient's daily routine |

| Provide written resources on the planned medication |

| Implement measures to avoid forgotten doses |

| Place the medication in a visible location |

| Use digital alarms and reminders on mobile devices |

| Use medicine dispensers or weekly blisters |

| Have a spare dose at hand to cover forgotten doses (wallet, office, car) |

| Arrange a pharmacotherapy and pharmaceutic care follow-up program |

| 7. Promote the continuum of care and schedule regular appointments. Telephone follow-up for patients who do not comply with the appointment schedule |

| 8. Identify and appoint a “case manager/coordinator” to manage the transition and advise the patient as appropriate |

| 9. Create a multidisciplinary medical team: schedule regular Committee of Experts meetings for patient follow-up |

| 10. Implement multidisciplinary care programs that contemplate prevention, detection and measures for improving therapeutic compliance |

| 11. Implement protocols for patient transition to adult care that ensure prevention, detection and treatment compliance |

| 12. Foster a good relationship between the patient/carer and medical team |

| 13. Implement protocol-based programs for the transition to adult care |

| Planning the medical appointment: |

| Check my schedule |

| Check my cystinosis medical kit and whether I need to renew my prescriptions |

| Check if I have any new documents from other specialists since my last medical visit |

| Attend prearranged blood tests and check whether these include a cystine level determination (remember to take Cystagon® 6h prior to the blood draw) |

| Check whether I am due any other complementary test prior to the medical visit |

| Go to the pharmacy department to pick up the scheduled medication |

| Before the medical appointment: |

| Write down any questions and/or doubts you want to raise with the medical team |

| Make a note of any symptoms or health problems you have experienced since your last appointment (since when, how it passes, what makes it worse) |

| Make a note of your blood pressure and glucose tests if your doctor tells you to do so |

| During the appointment: |

| Do not be afraid to ask as many times as is necessary in order to clarify any doubts you may have |

| Make a note of any information you wish to remember |

| Ask for your test results, including your cystine levels and medical tests |

| Ask the doctor or nurse to assess your results and how you are doing |

| Make sure you fully understand the instructions given to you by your doctor regarding changes to your treatment |

| Check that you have your new treatment regimen in writing, as well as up-to-date prescriptions |

| Before the appointment ends: |

| Check that you have written down the date of your next appointment |

| Make sure you have the contact details of your medical team (telephone and email) |

| Find out whether there have been any advances regarding your illness, and whether there are any patient association meetings or conferences that may be of interest |

| When you get home: |

| Check that you understand the treatment changes you were told about |

| Prepare your weekly medical kit in accordance with your new treatment regimen |

| Note down your next appointment in your diary |

| File any new documents |

| Make an appointment with your family doctor to explain the content of the visit and the changes made |

| Cystinosis dossier: |

| Prepare a file in which you can save any documentation in an orderly manner |

| Documents to include: |

| 1. Medical visit schedule |

| 2. List of contacts: |

| Hospital: appointment line, specialist physicians, nursing team, case manager |

| Primary Care Center |

| Patient Association |

| Other useful telephone numbers |

| 3. Medical reports ordered by date and specialist |

| 4. Immunization card |

| 5. Record of allergies, if any |

| 6. Any documents from appointments, examinations and blood tests, etc. |

| 7. Prescription monitoring |

| 8. Medication monitoring |

Adapted from “Information prescription for patients with cystinosis” – Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, with the authorization of Mr. Steven Wise-Renal Metabolic Disease Nurse Specialist.50

Granulocyte cystine levels ≤1nmol hemicystine/mg protein indicate good adherence to oral cysteamine, resulting in therapeutic efficacy. The issue of non-adherence emerges during adolescence and is generally more pronounced during the transition to adult units, affecting both treatment and clinical adherence (missed clinic appointments and complementary tests). Non-adherence to cysteamine is associated with worse prognosis and greater renal and extra-renal disease progression.4,19,43 Nevertheless, suboptimal treatment compliance is not restricted to cystinosis and has been observed in KTx and other chronic diseases.17,44

Numerous converging risk factors that affect treatment adherence in cystinosis patients include a strict dosing regimen, tolerance problems, potential side effects and a complex multi-drug treatment plan. Furthermore, other equally important considerations not exclusive to cystinosis are: limited knowledge of the disease, lack of motivation, inadequate transition to adult care and impact of the disease on quality of life.8,45 A further factor is that cystinosis patients often present neuropsychologic involvement and disabilities which, when accompanied by neurocognitive immaturity, may further affect the patient's ability to manage the chronic disease.41

Assessing treatment adherence is essential in the patient's clinical follow-up, compliance should be routinely included in their medical notes, with an open and positive attitude that permits the correction of any prescription deviations.46,47 Thus, it is recommended that the different professionals involved assess the patient's degree of adherence and actively intervene with measures for improvement40,44–49 (Table 6).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

The authors thank Mr. Steven Wise, specialist nurse in renal metabolic diseases, from the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, for permitting us to draw on his experience for the care of cystinotic patients, Christine O’Hara for her invaluable help with the English version of the manuscript and Olga Gálvez from Sarria Copy, Barcelona, for her support in the design of the figures for the T-CiS.bcn project.

Please cite this article as: Ariceta G, Camacho JA, Fernández-Obispo M, Fernández-Polo A, Gámez J, García-Villoria J, et al. Transición coordinada del paciente con cistinosis desde la medicina pediátrica a la medicina del adulto. Nefrología. 2016;36:616–630.