Crusted Scabies (Norwegian Scabies) is a rare and severe presentation of the skin infestation caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei (var. hominis) in patients with cellular immunity compromised. Affected patients may present thousands of parasites on the skin surface. Due to impaired immune response, manifestations may occur in a atypical pattern and pruritus may be mild or absent, which can lead to late diagnosis and worse prognosis.1–4

A female 47-year-old renal transplant recipient (transplant 16 years ago), with chronic graft nephropathy was admitted in our hospital with asymptomatic lesions on face for one year. She was taking cyclosporine, mycophenolate and prednisone and was hospitalized due to acute respiratory infection and decompensation of baseline nephropathy.

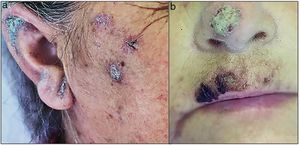

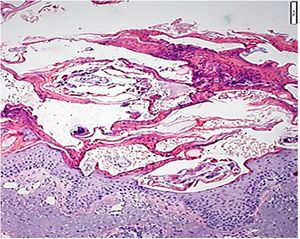

On dermatological examination, she presented erythematous-scaly plaques with greyish-yellow crusts on malar regions, ears, dorsum nasi and supralabial region (Fig. 1a and b). She denied itchiness or lesions on other areas. Considering chronicity of lesions and absence of specific findings on dermoscopy, we decided on performing a skin biopsy. Histopathology revealed pink spiral structures adhered to the stratum corneum, besides multiple mites identified as S. scabiei, and a diffuse infiltrate of eosinophils in the reticular dermis (Fig. 2). She was then treated with salicylate 3% mineral oil and permethrin 5% cream as topical therapy, and oral ivermectin (12mg, repeated 7 days later). She showed complete improvement of lesions.

Crusted Scabies (CS), also known as “Norwegian Scabies” a rare and severe presentation of the skin infestation caused by the mite S. scabiei (var. hominis) that can occur in patients with cellular immunity compromised, including those with graft-versus-host disease, HIV-AIDS, and those ones taking corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants.1,2 In this particular presentation, mites reproduce more effectively so that affected patients may carry thousands of parasites over the skin surface. It is highly contagious and minimal contact may be enough to lead to infection. Due to impaired cellular immune response, those patients may present atypical manifestations and pruritus may be mild or even absent, so that diagnosis can be challenging.1–4

CS differs from classic Scabies; it manifests as hyperkeratosis, especially on acral sites, but may be disseminated. It may also presents as crusts with erythematous base and lamellar scaling in areas such as scalp, face and neck.5,6 Secondary bacterial infection may occur, which increases the risk of bacteremia and sepsis.7 Besides the suggestive clinic, diagnosis of CS can be assisted by dermoscopy and microscopy, which allow the direct visualization in vivo of mites and eggs.8 Skin biopsy may confirm the diagnosis if it contains mites or eggs. However, clinical diagnosis may be challenging due to atypical presentation added up with mild or absent pruritus.6 In this case, our patient had long-term lesions, with exclusive facial involvement and complete absence of pruritus. On dermoscopic examination, features were not suggestive of scabies, so histopathology ended up confirming the diagnosis. Treatment of immunosuppressed patients with CS should combine topical permethrin with systemic ivermectin (repeated in 7–15 days). In addition, patient isolation and behavioural measures are necessary to prevent dissemination.1,2

Early diagnosis and treatment reduce the risk of transmission, outbreaks and severe evolution with associated bacterial infection.7 The main differential diagnosis must be done with crusted demodicidosis.9

Thus, atypical manifestations of scabies, especially in immunocompromised patients, should be considered, and direct microscopy and/or histopathology may be the key for the right diagnosis.

DeclarationsInformed consent to publish individual data was obtained from the patient.