The concept of brain death (BD) is accepted as synonymous with the death of a person and has been a turning point in the development of organ transplantation.1 Despite this, the concept has not been well assimilated by the population and is often associated with reversible coma states, leading to people being against organ donation due to the fear of not actually being dead.2 In recent decades, immigration has become an increasingly common phenomenon in Western society, with the African population being one of the largest immigrant groups. However, there are no data on awareness of BD in this population group, except for preliminary analysis data from projects presented at conferences.3–5 Our aim was to analyse knowledge of BD and the factors associated with it among Africans living in Spain.

A Spanish national epidemiological study was conducted in the population ≥15 years old born on the African continent and living in Spain. To calculate the size of the study population, a distinction was made between residents who had official documentation (data from Spain's National Institute of Statistics: n = 1,017,441) and those who did not (data obtained from information provided by 31 immigration support charities: n = 5,699,313). The estimated sample size was 4145 for the study population (n = 6,716,754), considering a favourable attitude of 50%, a confidence level (1–α) of 99% and a precision (d) of 2%. The sample was stratified according to nationality of origin, age and gender.

The measuring instrument was a validated PCID-DTO Ríos questionnaire6,7 on attitudes towards organ donation (total variance explained 63.203% and Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient of 0.834). A pilot study with a random sample (n = 100) confirmed the feasibility of the project and the need to translate the questionnaire into Spanish, English, German, French and Moroccan Arabic.

The assessment of the level of understanding of the concept of BD was established in the following terms: 1) Correct concept: the respondent accepts BD as death of the patient; 2) Wrong concept: the respondent does not accept BD as death of the patient; 3) Ignorance of the concept: the respondent states that he/she does not know the concept of BD.

In each of the population nuclei where sampling took place, it was confirmed that the potential respondent met the criteria for stratification by nationality, age and gender, and they were asked to give their verbal consent to take part. The questionnaire was self-completed anonymously.

The study was completed by 3618 respondents (87% completion rate), of whom 21% (n = 747) were aware of the concept, 61% (n = 2230) were unaware of it and the remaining 18% (n = 641) had a misconception.

A bivariate analysis was performed to assess which factors were associated with knowledge of the concept of BD, these being the respondent's country of origin (p < 0.001), gender (p = 0.007), marital status (p = 0.003), having children (p = 0.003), level of education (p < 0.001), having discussed transplantation in the family (p < 0.001), partner's attitude towards organ donation (p < 0.001) and the respondent's religion (p < 0.001).

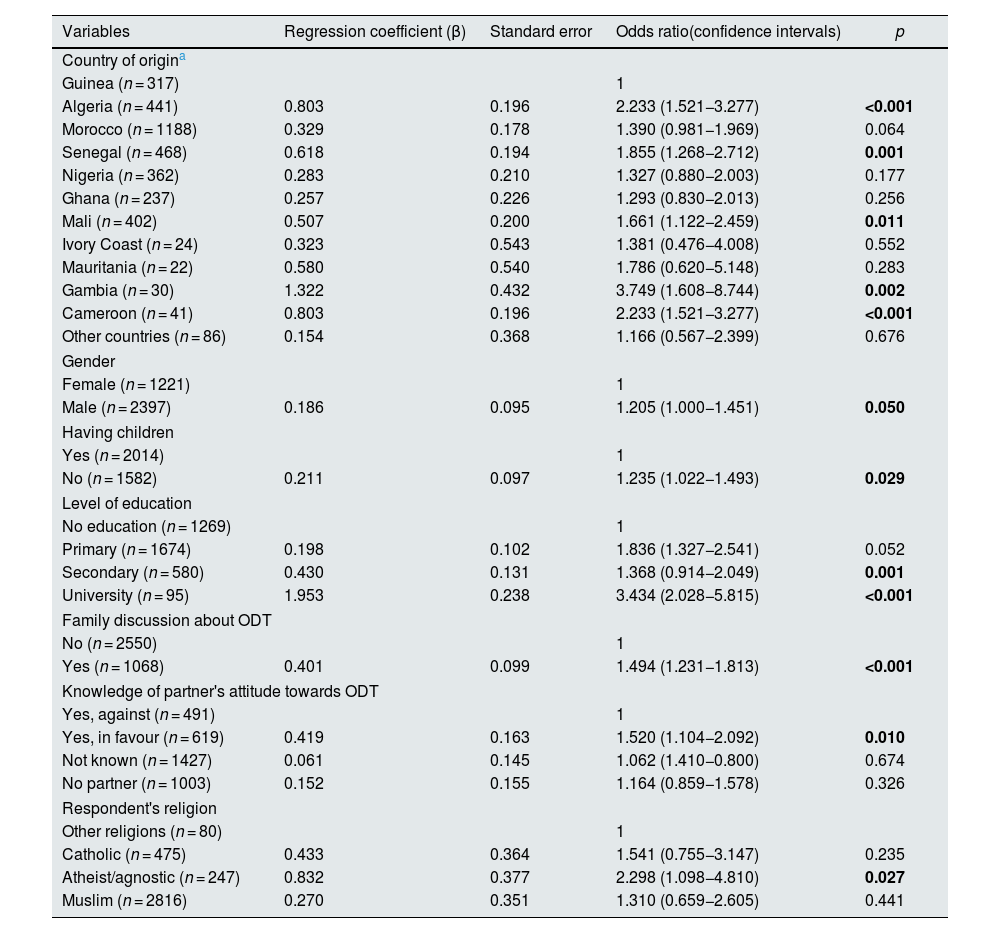

In the multivariate analysis, the following remained as independent variables associated with knowledge of the concept of BD (Table 1): 1) country of origin; 2) gender; 3) having children; 4) level of education; 5) having discussed organ donation and transplantation in the family; 6) the respondent's partner's attitude towards donation and transplantation; and 7) the respondent's religion.

Analysis of factors related to knowledge of the concept of brain death among Africans living in Spain. Multivariate analysis.

| Variables | Regression coefficient (β) | Standard error | Odds ratio(confidence intervals) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of origina | ||||

| Guinea (n = 317) | 1 | |||

| Algeria (n = 441) | 0.803 | 0.196 | 2.233 (1.521−3.277) | <0.001 |

| Morocco (n = 1188) | 0.329 | 0.178 | 1.390 (0.981−1.969) | 0.064 |

| Senegal (n = 468) | 0.618 | 0.194 | 1.855 (1.268−2.712) | 0.001 |

| Nigeria (n = 362) | 0.283 | 0.210 | 1.327 (0.880−2.003) | 0.177 |

| Ghana (n = 237) | 0.257 | 0.226 | 1.293 (0.830−2.013) | 0.256 |

| Mali (n = 402) | 0.507 | 0.200 | 1.661 (1.122−2.459) | 0.011 |

| Ivory Coast (n = 24) | 0.323 | 0.543 | 1.381 (0.476−4.008) | 0.552 |

| Mauritania (n = 22) | 0.580 | 0.540 | 1.786 (0.620−5.148) | 0.283 |

| Gambia (n = 30) | 1.322 | 0.432 | 3.749 (1.608−8.744) | 0.002 |

| Cameroon (n = 41) | 0.803 | 0.196 | 2.233 (1.521−3.277) | <0.001 |

| Other countries (n = 86) | 0.154 | 0.368 | 1.166 (0.567−2.399) | 0.676 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female (n = 1221) | 1 | |||

| Male (n = 2397) | 0.186 | 0.095 | 1.205 (1.000−1.451) | 0.050 |

| Having children | ||||

| Yes (n = 2014) | 1 | |||

| No (n = 1582) | 0.211 | 0.097 | 1.235 (1.022−1.493) | 0.029 |

| Level of education | ||||

| No education (n = 1269) | 1 | |||

| Primary (n = 1674) | 0.198 | 0.102 | 1.836 (1.327−2.541) | 0.052 |

| Secondary (n = 580) | 0.430 | 0.131 | 1.368 (0.914−2.049) | 0.001 |

| University (n = 95) | 1.953 | 0.238 | 3.434 (2.028−5.815) | <0.001 |

| Family discussion about ODT | ||||

| No (n = 2550) | 1 | |||

| Yes (n = 1068) | 0.401 | 0.099 | 1.494 (1.231−1.813) | <0.001 |

| Knowledge of partner's attitude towards ODT | ||||

| Yes, against (n = 491) | 1 | |||

| Yes, in favour (n = 619) | 0.419 | 0.163 | 1.520 (1.104−2.092) | 0.010 |

| Not known (n = 1427) | 0.061 | 0.145 | 1.062 (1.410−0.800) | 0.674 |

| No partner (n = 1003) | 0.152 | 0.155 | 1.164 (0.859−1.578) | 0.326 |

| Respondent's religion | ||||

| Other religions (n = 80) | 1 | |||

| Catholic (n = 475) | 0.433 | 0.364 | 1.541 (0.755−3.147) | 0.235 |

| Atheist/agnostic (n = 247) | 0.832 | 0.377 | 2.298 (1.098−4.810) | 0.027 |

| Muslim (n = 2816) | 0.270 | 0.351 | 1.310 (0.659−2.605) | 0.441 |

ODT: organ donation and transplantation.

In bold, significant p-values.

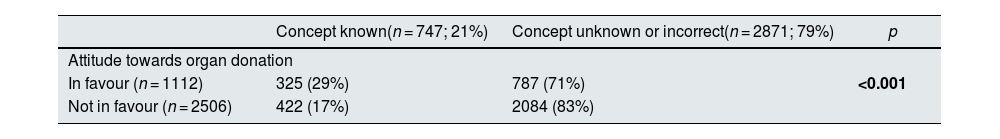

The attitude towards own organ donation was favourable in 31% of respondents (n = 1112), and there was a significant association with correct knowledge of the concept of BD, as can be seen in Table 2.

Relationship between attitude towards organ donation and knowledge of the concept of brain death (BD).

| Concept known(n = 747; 21%) | Concept unknown or incorrect(n = 2871; 79%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude towards organ donation | |||

| In favour (n = 1112) | 325 (29%) | 787 (71%) | <0.001 |

| Not in favour (n = 2506) | 422 (17%) | 2084 (83%) | |

In bold, significant p-values.

The African population living in Spain is an emerging and growing population group. The results of our study show that awareness and acceptance of the concept of BD is very low in this population, with only 21% accepting it. Using the same questionnaire as in this study, we analysed knowledge of the concept of BD in the Latin American immigrant population in Spain, and found a similar level, where only 25% were aware of the concept.8 It is noteworthy that this percentage is much lower than in the native Spanish population, where 51% claim to know and accept this concept as the death of a person.9 It is important to acknowledge that the research population is very heterogeneous and that there are significant differences between nationalities. For example, 37% of Guineans surveyed are aware of it and accept it, although that is still well below the levels recorded in Western societies.9

Most studies on this topic indicate a close relationship between knowledge and acceptance of the concept of BD and attitudes towards organ donation.2,9,10 This study found that those who accepted the concept of BD were more in favour of organ donation than those who did not. Overall, based on this association, it has been suggested that increasing awareness and acceptance of the concept of BD could contribute to improving attitudes towards organ donation and transplantation.2,6–10

In addition to nationality, awareness of this concept is mainly related to the level of education, religion and family background, especially the partner's attitude towards organ donation. It is therefore considered beneficial to encourage dialogue on the topic of organ donation in family circles and with partners.2,9

To conclude, we have found that knowledge of the concept of BD among Africans living in Spain is very low, with marked differences according to the African country of origin and other socio-personal factors.

Authors’ contributionsConception and design: Ríos A.

Collection of a substantial part of the data: Ríos A, Carrillo J, López-Navas A and Ayala-García MA.

Data analysis and interpretation: Ríos A, López-Navas A, Ramírez P and Alconchel F.

Drafting of the manuscript: Ríos A, López Navas A and Carrillo J.

Critical revision of the manuscript: Ríos A and López-Navas A.

Statistical review: Ríos A and López-Navas A.

Obtaining funding for this project: Ríos A.

Supervision: Ríos A.

Approval of the final version: Ríos A, Carrillo J, López-Navas A, Ayala-García MA, Ramírez P and Alconchel F.

FundingStudy co-funded by a Mutua Madrileña research project (ID98FMM020).

Conflicts of interestThere are no conflicts of interest.

This study would not have been possible without the collaboration and support of the 31 immigrant associations that contributed to the creation and completion of the project.