Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) affects prognosis in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (ACKD). A high prevalence of classic and occult HCV has been described in the haemodialysis population.1,2 Although we are in a new era of antiviral treatment, there are no studies supporting the indication of this therapy in patients with occult HCV infection yet. The ACKD population that is to receive future immunosuppression appears to be at risk for viral replication. Therefore, it would bear considering pre-immunosuppression antiviral treatment.3 There is just 1 published case on the subject, although that patient did not have renal disease.4 This letter presents the clinical course of occult HCV in 2 patients with ACKD who received immunosuppressive therapy. The determination of occult HCV was performed in la Fundación para el Estudio de las Hepatitis Virales (the Foundation for the Study of Viral Hepatides), using ultracentrifugation of serum5 and ultrasensitive PCR in the liver and in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC).6 In recent years, the high-sensitivity anti-HCV core antibody detection technique has been added.7

Case 1A 40-year-old woman, smoker, with systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid syndrome, hypertension, tertiary hyperparathyroidism, osteoporosis, hyperhomocysteinaemia, and hyperuricaemia. She began haemodialysis in 1990 (renal transplant from 1991 to 1998). Regular medications were cinacalcet, aluminium hydroxide, calcium acetate, risedronate, folic acid, multivitamin B1/B6/B12, omeprazole, allopurinol, carvedilol, hydroxychloroquine, acenocoumarol, iron, and intradialytic darbopoetin.

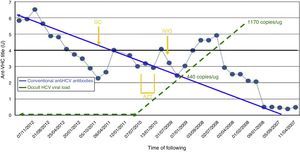

From March 2008, serial “indeterminate” results were ascertained (ELISA, RIMA) for HCV (positive only for the NS3 fraction). Several retests were carried out, and cross-reaction testing was performed for underlying autoimmune disease. Despite normal blood transaminase levels, the possibility was raised of occult HCV. This was confirmed in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC, 1170copies/μg total RNA), and in the liver. Further investigations were performed: transjugular liver biopsy, showing chronic hepatitis grade/stage 0/0; FibroScan®, 6.3KPa; APRI, 0.81; and Forns score, 7.59. Potential external contamination was tested for, but did not occur: viral PCR and serology were performed on the other patients in the unit and the healthcare staff. No new cases of classic HCV infection were detected. In February 2009, the patient received intravenous immunoglobulin IVIG (2g/kg) for pretransplant desensitisation (in the end, transplant was not performed, for other reasons), and from June to November 2009 she received azathioprine (AZT 50mg/day) and corticoid therapy (GC 5mg/day) for lupus activity. There was no observed increase in the intralymphocyte viral load, although there was an immune response (Fig. 1). In March and April 2009, there was a transient mild increase in ALT, with a maximum level of 42UI/L.

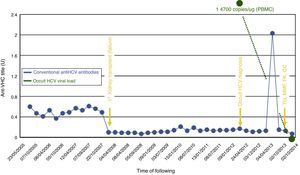

Case 2A 51-year-old man with ACKD of unknown aetiology and hypertension, who began dialysis in 2005. His first renal transplant failed immediately due to non-immunological arterial thrombosis in October 2007. During that admission he received 2 units of red blood cells. Transaminases were sporadically raised in 2009, with a sustained increase in December 2010 (maximum level 28/40UI/L AST/ALT). Occult HCV was diagnosed with 14700copies/μg total RNA in PBMC (RNA negative in serum on ultracentrifugation and high-sensitivity anti-HCV core antibody negative). Ultrasound and FibroScan® were normal. Potential external contamination was tested for, but did not occur: viral PCR and serology were performed in the other patients in the unit and the healthcare staff. No new cases of classic HCV infection were detected. The patient received a second renal transplant in October 2013 and was treated with thymoglobulin (TG), tacrolimus (FK), mycophenolate (MMF), and corticoids. Seventeen months post-transplant, PBMC viral load was undetectable, and RNA on serum ultracentrifugation and high-sensitivity anti-HCV core antibody both remained negative (Fig. 2).

Changes in conventional anti-HCV antibodies and occult HCV viral load. Laboratory threshold for positivity for anti-HCN antibodies (HCV Ab), 4 UI. PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; Dx, diagnosis; FK, tacrolimus; GC, glucocorticoids; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; TG, thymoglobulin; Tx, transplant.

The infectivity8 and pathogenicity of occult HCV have been described, but there is still insufficient experience to justify HCV eradication. Currently, only cases in research protocols have been treated.3

There is evidence, though very little, of HCV replicator activity in the presence of immunosuppressive stimuli.4 Therefore, in hyperimmunised patients requiring aggressive immunosuppression in the peritransplant period, including long-term corticoid therapy, doubt remains as to whether pre-transplant antiviral therapy should be considered.

This letter presents the second and third cases from the literature of patients with occult HCV who received immunosuppressive therapy. These are the first described cases with ACKD. In the first case presented here, which occurred following AZT, the intralymphocyte viral load did not increase, and even decreased to undetectable levels, whilst the antibody titre increased. This suggests that the patient's immune system, though supposedly weakened, overcame the viraemia. In the second case, the viral load was cleared to negative, but without the production of immune antibodies against the virus (there was an increase in the level of antibodies, but this was transient and did not reach the laboratory threshold).

The observed activity of the immunity/virology relationship cannot be explained based on this experience alone. Quiroga et al.9 demonstrated that occult HCV did induce a CD4+/CD8+ cellular response in immunocompetent patients, but without detection of specific antibodies. However, little is known about HCV activity in immunocompromised patients, particularly when taking into account, the different types and degrees of immunosuppression that exist, including that proportionally related to uraemia.

ConclusionIn conclusion, there is insufficient evidence to justify antiviral treatment in patients with chronic kidney disease and occult HCV, even when immunosuppressive treatment is anticipated. Therefore, we remain expectant and await further results.

Please cite this article as: Martín-Gómez MA, Castillo-Aguilar I, Barril-Cuadrado G, Cabezas-Fernández T, Casado-Martín M, Cabello-Díaz M. Evolución del virus de la hepatitis C oculto tras inmunosupresión en enfermedad renal crónica avanzada. Nefrologia. 2015;35:511–513.