Infection with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) is one of the main problems that can negatively affect the outcomes of renal transplant (RT).1 With new immunosuppressors, short-term outcomes have improved. However, the longer-term prognosis does not run a parallel course and there is some disagreement about how to improve survival rates and outcomes in these patients. These facts could be explained, at least partly, by the barrier caused by HCV infection.2 In RT patients, HCV can alter the course of liver disease and cast a shadow over the prognosis of these patients.3

It has been reported that the primary cause of RT loss in late stages is death in patients with a functioning graft, while death due to liver disease is, in almost all the reports, between the fourth and fifth cause of death in this population. Renal recipients with HCV have been shown to have a higher incidence of severe opportunistic infections, post-transplant diabetes mellitus, and glomerular diseases, including chronic graft nephropathy. Liver failure is responsible for 8–28% of deaths in the long-term in RT.1

It is known that 7–24% of RT recipients have biochemical abnormalities in liver function. 50% of these abnormalities arise from infection with hepatitis B virus, cytomegalovirus, or Epstein–Barr virus; toxic processes due to drugs such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine A, and tacrolimus; as well as alcohol abuse, haemosiderosis, and neoplastic disease affecting the liver. The other 50% of liver disease in patients with a renal allograft is caused by HCV.4 It is important to highlight that between 70% and 95% of transplant patients with HCV have active infection, probably due to immunosuppressive treatment.

Infection with HCV is common in patients with end-stage renal failure on haemodialysis, and the prevalence ranges from 10% to 65%, depending on the geographic area. In France, the prevalence is 10.4% of patients enrolled in dialysis programmes, while in the United States, Japan, and Italy, the prevalence reaches 14%, 14.8%, and 20.6%, respectively.5 In Spain, 30% of chronic renal patients awaiting RT of have positive hepatitis C virus antibodies (anti-HCV+). According to the Spanish Registry of Chronic Graft Nephropathy, in recent years, the prevalence of this infection has decreased significantly in transplant patients (6%), contributing to better outcomes in the longer-term.6

In countries where infection is endemic (Egypt, Japan, and counties in Southeast Asia), approximately 50% of the dialysis population is infected. Even in countries with a low prevalence of HCV, such as England and New Zealand, the rate ranges between 3% and 5%, representing a rate 10 times higher than that of the general population.7

In Latin America, the prevalence of HCV in haemodialysis is variable. In Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia, it is 67%, 52%, and 53%, respectively. In Cuba, 52% of patients receiving haemodialysis are HCV-positive.8 In the Haemodialysis unit of the Hospital de Camagüey (Cuba), half of the patients are infected with HCV at between 6 and 12 months after starting haemodialysis. The most common risk factors are blood transfusion and re-use of dialysers. Currently, the prevalence of HCV in haemodialysis is 58.66%, and in patients described as suitable for RT, 63% have HCV acquired during haemodialysis.

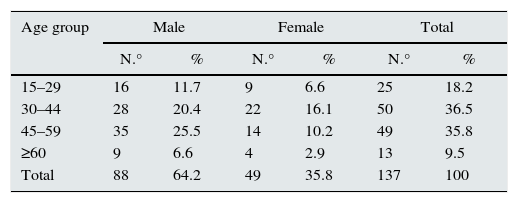

A cohort study was conducted to compare the general outcomes of RT recipients with HCV acquired during haemodialysis, against recipients without HCV, in the Renal Medicine Department of the Hospital Universitario Manuel Ascunce Domenech de Camagüey (Cuba), in the period from 01/2003 to 12/2012. This population comprises all patients who have received RT, of which 137 patients who met the inclusion criteria were taken as a sample (Table 1).

Distribution by age and sex. Renal Medicine Department, Hospital Universitario Manuel Ascunce Domenec, Camagüey, 2011–2012.

| Age group | Male | Female | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N.° | % | N.° | % | N.° | % | |

| 15–29 | 16 | 11.7 | 9 | 6.6 | 25 | 18.2 |

| 30–44 | 28 | 20.4 | 22 | 16.1 | 50 | 36.5 |

| 45–59 | 35 | 25.5 | 14 | 10.2 | 49 | 35.8 |

| ≥60 | 9 | 6.6 | 4 | 2.9 | 13 | 9.5 |

| Total | 88 | 64.2 | 49 | 35.8 | 137 | 100 |

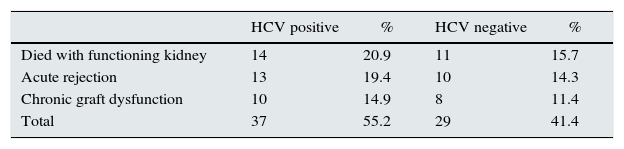

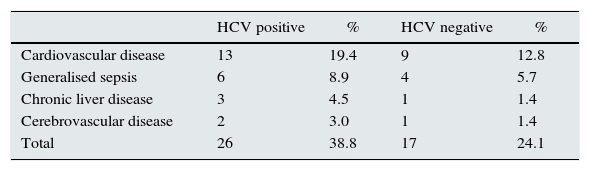

There was a high prevalence of HCV in the transplanted population. There was an increased tendency to develop post-transplant diabetes mellitus and acute rejection in HCV-positive patients. Patient death and acute rejection were the most common causes of loss of graft function. Cardiovascular disease and generalised sepsis were the most common causes of death. In patients with HCV, graft and recipient survival were lower than in those without HCV. Most transplanted patients were 30–40 years old and male (Tables 2 and 3).

Causes of loss of graft function. Renal Medicine Department, Hospital Universitario Manuel Ascunce Domenech, Camagüey, 2011–2012.

| HCV positive | % | HCV negative | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Died with functioning kidney | 14 | 20.9 | 11 | 15.7 |

| Acute rejection | 13 | 19.4 | 10 | 14.3 |

| Chronic graft dysfunction | 10 | 14.9 | 8 | 11.4 |

| Total | 37 | 55.2 | 29 | 41.4 |

Main causes of mortality. Renal Medicine Department, Hospital Universitario Manuel Ascunce Domenech, Camagüey, 2011–2012.

| HCV positive | % | HCV negative | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular disease | 13 | 19.4 | 9 | 12.8 |

| Generalised sepsis | 6 | 8.9 | 4 | 5.7 |

| Chronic liver disease | 3 | 4.5 | 1 | 1.4 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2 | 3.0 | 1 | 1.4 |

| Total | 26 | 38.8 | 17 | 24.1 |

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Millet Torres D, Curbelo Rodríguez L, Ávila Riopedre F, Benítez Méndez M, Prieto García F. Evolución general de receptores de trasplante renal con hepatitis C, en el hospital provincial de Camagüey, Cuba. Nefrologia. 2015;35:509–511.