The coordination between nephrology and primary care is well documented in the management of chronic kidney disease (CKD), but the real impact is uncertain.

ObjectiveTo evaluate the efficiency of an outpatient nephrology programme (ONP) implanted progressively over the course of 10 years regarding the demand for CKD care in the Integral Health Area of Barcelona Esquerra, accounting for 524,395 inhabitants, which is more than a third of the population of Barcelona.

Material and methodsThe number and age of the new referrals to nephrology between 2004 and 2014 were identified and a referral index (RI) was established between the number of new referrals and the estimated prevalence of CKD in the population treated, based on the implementation of the ONP.

ResultsThe adult population decreased between 2006 and 2014, but the number of inhabitants aged 65 years or above increased from 107,025 to 113,461 and so did the estimated CKD. Renal insufficiency was the reason for more than 70% of the referrals made to nephrology. The average age was 74 years old between 2004 and 2009 and 70 between 2010 and 2014. The RI showed two trends in the analysed period, depending on whether or not the ONP included the face-to-face consultancy.

ConclusionsThe decrease in RI suggests a better resolution at primary care. The major improvement in the Basic Health Areas of reference (with RI reduced by more than 44%) coincides with the implementation of the ONP. The implantation of ONP overcome the gap between primary and hospital care in order to respond to chronicity, ageing and dependence.

La coordinación entre nefrología y atención primaria se recoge bien en documentos sobre el manejo de la enfermedad renal crónica (ERC), pero se conoce menos el impacto real.

ObjetivoEvaluar la eficiencia de un programa de nefrología extrahospitalaria (PNE) implantado progresivamente en 10 años respecto la demanda de atención a la ERC en el Área Integral de Salud Barcelona Esquerra, 524.395 habitantes, más de un tercio de la población barcelonesa.

Material y métodosSe ha recogido el n. y la edad de las 1.ªs visitas en nefrología entre 2004 y 2014 y establecido un índice de derivación (ID) entre el n. de 1.ªs visitas y la ERC estimada en población atendida según la implantación del PNE.

ResultadosLa población adulta descendió entre 2006 y 2014, pero el n. de habitantes ≥65 años aumentó de 107.025 a 113.461, así la ERC estimada. Insuficiencia renal fue el motivo de >70% de las 1.as visitas de nefrología. La media de edad fue 74 años en 2004-2009 y 70 años en 2010-2014. El ID mostró dos tendencias en el periodo analizado según el PNE incluyera consultoría presencial o no.

ConclusionesEl descenso del ID sugiere mejor resolución de la atención primaria. La mejora mayor en las Àreas Básicas de Salud de referencia (con ID reducido hasta >44%) coincide con la implantación del PNE. Precocidad y contención del PNE superan la brecha entre la atención primaria y la hospitalaria a fin de dar respuesta a la cronicidad, el envejecimiento y la dependencia.

The high prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the adult population,1 the fact that it is underdiagnosed and its progressive but modifiable nature have made necessary to develop specific prevention and detection strategies. The aim of these strategies is to avoid associated cardiovascular complications, progression of CKD and inadequate prescription of medications. The aim is also to avoid late referral to the nephrologist to avoid a delay in adequate control of the complications of advanced CKD which makes difficult to prepare the patient in advance for renal replacement therapy.

Primary prevention of CKD in the at-risk population is essentially based on detecting kidney disease and preventing renal progression factors. CKD is detected through estimation of glomerular filtration rate from creatinine-derived formulas and determining the albumin/creatinine ratio in a first morning urine sample. Prevention includes controlling blood pressure, optimisation of blood glucose control in diabetics, avoiding smoking and obesity, and control of dyslipidaemia and other cardiovascular risk factors.2 The detection and confirmation of CKD requires follow-up by the primary care physician and a nephrology specialist when necessary. Over the last ten years, thanks to the close collaboration and coordination achieved between nephrology and primary care, consensus documents have been published by the main scientific societies involved in care of kidney patients.3,4 However, not so much is known about the real impact on kidney health care. The reason for this gap of knowledge is related to the fact that nephrology speciality has always been seen as a “necessarily hospital-based specialist area”.

We assessed the efficiency of an out-of-hospital nephrology programme (ONP) implemented progressively over ten years with respect to control of the demand for CKD care in the Barcelona Esquerra Integral Health Area. We compared nephrology referrals in the fourth year of implementation (2010) to referrals after a further four years (2014).

The Integral Health Areas (IHA) were set up as a project by the Barcelona Health Consortium and health service providers with the aim of improving healthcare in the city of Barcelona through the effective coordination of the providers and healthcare professionals. There are four IHAs: “Norte”, “Esquerra”, “Derecha” and “Litoral”. Our experience came under the scope of the Barcelona Esquerra Integral Health Area. This area has a population of 524,395, which is 35% of the population of Barcelona and 7% of the population of Catalonia, for which the Nephrology and Kidney Transplant Department at Hospital Clínic is the single point of referral for the speciality.

Material and methodsBarcelona Esquerra Integral Health AreaThe providers of primary care services in the 19 basic health areas that form part of the IHA-BE are the Consorcio de Atención Primaria de Salud de Barcelona Esquerra (CAPSBE) [Barcelona Esquerra Primary Health Care Consortium], consisting of the Instituto Catalán de la Salud (ICS) [Catalan Health Institute] and Hospital Clínic of Barcelona, for care provision in three basic health areas (4-C, 2-E and 2-C); and the ICS for 13 basic health areas (2-A, 2-B, 2-D, 3-B, 4-A, 4-B, 5-A, 5-B, 3-C, 3 -D, 3-E, 3-G and 3-H). Three basic health areas (5-C, 5-D and 3-A) are managed as Entidades de Base Asociativa (EBA) [limited companies] by the healthcare professionals themselves (Fig. 1A).

The assigned population was obtained from the Catalan Health Service (CatSalut) central registry of people covered by health insurance, an automated file for managing the individual health card that allows identification of those covered from their personal identification code, their basic health area and their allocated primary care provider unit. The adult population of 450,027 in 2006 had fallen to 438,782 by 2014. However, the number of people aged 65 or over has increased from 107,025 to 113,461, with a corresponding increase in the estimation of CKD in the population (Table 1).

Population assigned to the Barcelona Esquerra Integral Health Area (IHA-BE).

The population attended in primary care is the population assigned to a Primary Care Team (PCT) which ultimately received care from that PCT during a delimited period, normally one year. The figures were obtained directly from the different providers involved.

Out-of-hospital Nephrology ProgrammeIn order to support primary care doctors in the zone of reference, the ONP was developed in three phases:

Phase I: analysis of healthcare organisation in the IHA-BE in 2005.

Phase II: implementation of the ONP in the CAPSBE basic health areas: 4-C (Les Corts PCT) in 2006, 2-C (Borrell PCT) and 2-E (Casanova PCT) in 2007.

Phase III: extension of the ONP to eight ICS basic health areas: 2-A, 2-B, 2-D, 3-B in 2008, and 4-A, 4-B, 5-A and 5-B in 2010.

The ONP provided a referral nephrologist for quick consulting about case reports by corporate email, and in person for consulting about specific cases, at the discretion of the primary physician. The nephrologist travelled monthly to the primary health centre (PHC) for a 1–2h clinical/teaching session in Phase II and every two months in Phase III. In the basic health areas with virtual and face-to-face nephrology consultancy, continuing education nephrology sessions were also held every four months.

In the remaining eight IHA-BE basic health areas, the consult to the nephrologist was only virtual via e-mail; the nephrologist did not have to move to the PHC (Fig. 1B).

As part of the actual visits to the PHC in 2008, the nephrology consultant circulated the “Nephrology Clinical Practice” guidelines developed for the joint management in primary and specialised care of CKD, diabetic nephropathy, hypertension and polycystic kidney disease. Also imparted were “Criteria for referral to nephrology” according to age, gender, serum creatinine level and GFR <60ml/min/1.73m2 or <30ml/min/1.73m2. In 2010 they distributed the “SEN-SEMFYC Consensus Document”3 from the Spanish Nephrology Society and the Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine, containing the referral criteria from primary to specialised care and a set of recommendations on renal patient care in the primary care setting. That was followed in 2012 by the “SCN-CAMFiC-SCHTA-ACI-ACD Consensus Document”,4 written along the same lines by the Catalan Society of Nephrology, the Catalan Society of Family and Community Medicine, the Catalan Society of Arterial Hypertension, the Catalan Nursing Association and the Catalan Diabetes Association respectively, in collaboration with the Catalan Autonomous Government Department of Health.

Every year since 2007, a nephrology training session specifically for primary care has been run for IHA-BE. The twelfth edition was held in 2018.

Chronic kidney diseaseIn order to estimate CKD we applied the EPIRCE1 study in population assigned between 2004 and 2014 and the EROCAP5 study in population seen, registered and available in general from 2010. Before that date the heterogeneity of registries between the different providers did not allow rigorous application.

We collected the number and age of the patients referred from the basic health areas of the IHA-BE between 2004 and 2014 and seen as new nephrology referrals. The reason for referral to nephrology has been registered since 2008.

The request for referral to nephrology from primary care was assessed regardless of whether the PHC only had a virtual consult to nephrology or both a virtual and face-to-face nephrology consult.

We established a referral ratio (RR) between the number of new referrals attended in nephrology and the estimated CKD in the population of in the basic health area according to the formula:

Number of new referrals to nephrology×1000/Number of patients seen in primary care estimated to have CKD

We compared the RR, expressed as a fraction of 1000, between the number of new referrals and the estimated CKD in population treated in the basic health area grouped according to the implementation of the ONP with face-to-face or virtual consult only to assess the impact of the ONP during the period 2004–2014.

ResultsThe mean age of the patients who were new nephrology referrals was 74 from 2004 to 2009 and 70 from 2010 to 2014. The median age showed a similar decrease between the two periods, 79 and 74 respectively.

The reason for the first referral to nephrology was renal failure, estimated GFR <60ml/min/1.73m2, in 72% of patients referred from primary care in IHA-BE territory. A 19% of patients were consulted for proteinuria >1g/d with a normal kidney function and the remaining 9% were patients seen in nephrology for a other kidney disorder.

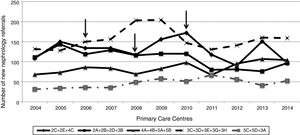

The new referrals seen in nephrology during the period 2004–2014 requested from primary care in the IHA-BE territory are shown in Fig. 2. These referals are grouped according to the provider and the ONP mode: virtual only or virtual and face-to-face. The number of new referrals from the primary care centres to be seen as face-to-face in nephrology consults decreased from the date of implementation of the face-to-face mode, while the number of new referrals with virtual nephrology consults remained at the same level on the evolution curve.

Table 2 shows the impact of the ONP on the relationship between care levels. The effective referral ratio calculated as the number of new nephrology referrals and the estimated CKD in the population tin primary care decreased significantly at the centres with ONP including face-to-face consulting.

Population served in the IHA-BE in 2010 and 2014. New nephrology referral ratio, expressed as a fraction of 1000 of the population treated estimated to have CKD, according to the nephrology consultancy, whether virtual and face-to-face or virtual only.

| Out-of-hospital Nephrology Programme | Basic Health Area | Year | Population seen aged >18 | Population seen aged >70 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | CKD estimation* (21.3%) | Number of new nephrology referrals | New referral ratio ‰ | Number | CKD estimation * (33.7%) | Number of new nephrology referrals | New referral ratio ‰ | |||

| Virtual and face-to-face nephrology clinic | 4C+2C+2E | 2010 | 65,114 | 13,869 | 172 | 12.40 | 19,289 | 6500 | 99 | 15.23 |

| 2014 | 59,600 | 12,695 | 97 | 7.64 | 15,809 | 5328 | 60 | 11.26 | ||

| 2A+2B+2D+3B | 2010 | 64,503 | 13,739 | 120 | 8.73 | 15,075 | 5080 | 78 | 15.35 | |

| 2014 | 60,998 | 12,993 | 97 | 7.47 | 15,059 | 5075 | 40 | 7.88 | ||

| 4A+4B+5A+5B | 2010 | 54,964 | 11,707 | 98 | 8.37 | 15,798 | 5324 | 66 | 12.40 | |

| 2014 | 53,768 | 11,453 | 104 | 9.08 | 16,665 | 5616 | 52 | 9.26 | ||

| Virtual nephrology consultancy | 3C+3D+3E+3G+3H | 2010 | 87,235 | 18,581 | 147 | 7.91 | 18,642 | 6282 | 98 | 15.60 |

| 2014 | 82,387 | 17,548 | 159 | 9.06 | 19,190 | 6467 | 93 | 14.38 | ||

| 5C+5D+3A | 2010 | 48,121 | 10,250 | 51 | 4.98 | 12,393 | 4176 | 24 | 5.75 | |

| 2014 | 31,664 | 6744 | 52 | 7.71 | 18,259 | 6153 | 34 | 5.53 | ||

This study is the first of its kind in Spain to analyse the impact of out-of-hospital nephrology care depending on whether the nephrologist consult is virtual or face-to-face, and the influence on referrals to specialised hospital nephrology care.

In 2006, we started an ONP in one of the three CAPSBE centres run by the ICS and Hospital Clínic de Barcelona. We later expanded the programme to the remaining two CAPSBE primary health centres and by 2010 we had expanded to eight more basic health areas managed by the ICS. The ONP provided a referral nephrologist, consultancy for case reports and continuing education sessions. The consultation was organised through the referral nephrologist by email and in person with the nephrologist travelling to the primary health centre. In the rest of the IHA-BE basic health areas only virtual consultancy has been available by email. The adequacy of the primary care referral to nephrology was assessed by a nephrologist, not involved in the out-of-hospital consultancy, for the entire IHA-BE territory, regardless of whether the referral nephrologist for the PHC was virtual only or also face-to-face.

In 2015, in line with the strategy to complement the high complexity of our tertiary hospital on the development of health policies on care provision for the chronically ill, it was decided to extend the ONP to the entire territory of the IHA-BE, beyond the limitation of the “Reform of Specialised Care”, with respect to nephrology being considered as a purely “hospital-based specialist area”. In the established framework of an organisational model based on, among other axioms, decision making from clinical knowledge and the use of information system tools to facilitate coordination between the different levels of care,6 we analysed the impact of the ONP in terms of controlling the demand for referral to the nephrology department throughout the period 2004–2014, in order to assess how the ONP was extended to all of the basic health areas of reference.7

The referral ratio of the number of new referrals to the estimated population with CKD remained unchanged even in a population that is older, and consequently more chronic, population, suggesting better efficacy by primary care in the period analysed. The decrease in the referral ratio was higher in the basic health areas with an ONP implemented with face-to-face consulting in addition to the virtual consultancy. The notable improvement, with a drop in the referral ratio of over 44% in basic health areas 2A, 2B, 2D and 3B, completely coincided with the implementation of face-to-face nephrology consulting in the period analysed. This shows that the degree of collaboration between primary and specialised care is enhanced by the closer contact between the two areas.

Our study does have certain limitations. Firstly, the sociodemographic characteristics of the assigned population may contribute to differences in demand in the different basic health areas. CKD can access care in the public health system at different stages of evolution and the rate of referral to specialised care is therefore heterogeneous. Moreover, the complexity of the service provision and process management within the IHA-BE territory may affect referral to nephrology. Secondly, the nephrology referral rate registers the appointments made, but we do not know how many requests for referral from primary care were rejected.

With the increased in life expectancy of the general population and in patients with advanced CKD, the amount of care aiming to guarantee quality of life also increases. Of course this is a relative depending on the disease causing CKD (e.g. diabetes mellitus), personal aspects (education), psychosocial aspects (family integration), adaptation to the environment (social integration), and therapeutic advances8 (e.g. erythropoiesis-stimulating agents). Continuity of care promotes a more effective and trusting relationship between patients and healthcare professionals, and helps to improve understanding of health problems and better adherence to the treatment prescribed. These benefits are mostly perceived in patients who need to visit the primary care physician frequently. It was recently reported that patients with continuity of care in primary care, more than 18 visits in the study period of two years (2011–2013), had a 12.49% reduction of hospital stays as compared with patients with less continuity of care.9

The approach in terms of health to population ageing, chronicity and associated mortality requires cooperation between the different levels of care and overcoming of the gap between primary and specialised care10 if we are to achieve efficiency, effectiveness and justice in the use of healthcare resources. Out-of-hospital nephrology provides the “continued care” of the chronic renal patient.

The ONP, particularly those that encourage involvement of the specialist in the healthcare team in person, in line with the “open hospital, without walls” concept,11 may overcome the gap between primary and hospital care in a radical but controlled manner, helping to respond to the challenges of chronicity, ageing and dependence. Studies based on the progressive indicators in CKD, percentage of hospitalisations, etc. will contribute more knowledge to the clinical impact of out-of-hospital nephrology.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Arrizabalaga P, Gomez M, Menacho I, Pallisa L, Jorge V, Poch E. La contribución de la nefrología extrahospitalaria al control de la demanda: análisis del Área Integral de Salud Barcelona Esquerra (AISBE). Nefrologia. 2019;39:192–197.