The term “health disparities” refers to those differences in health status experienced by different demographic groups that occur in the context of social or economic inequality. Health disparities affect access to services and quality of care, which is reflected by the increase in the morbidity and mortality of chronic diseases.1

In countries where medical care for chronic kidney disease (CKD) is not universal, treatment for this disease represents a devastating medical, social and economic problem for patients and their families; thus, the costs of treating this disease are considered as “catastrophic health expenditures.” A catastrophic health expenditure can be defined as one where the whole family spends more than 30% of their income to pay for the family's healthcare.2

In industrialised countries, CKD disproportionately affects socially disadvantaged groups, such as ethnic minorities and people with a low socioeconomic income.3 Multiple studies conducted in the United States and Canada have shown a strong association between low socioeconomic status and higher incidence and prevalence and more complications related to CKD. Crews et al.4 showed that people with a lower socioeconomic status had a 59% greater risk of developing CKD. This association was higher in the black population. Also, residence in poor neighbourhoods was found to be strongly associated with an increased prevalence of CKD.

In Europe, the relationship between socioeconomic status and CKD has been less studied; however, studies in Sweden, the UK and France have also found this association.5,6

Unfortunately, there are few studies in industrialising countries like India and Mexico. In these countries, there is a high prevalence of the disease in the socioeconomically disadvantaged population.7 In Central America, particularly in Nicaragua and El Salvador, there have been reports of a new kidney condition called Mesoamerican nephropathy, which occurs mainly in poor workers who toil in suboptimal working conditions at extreme ambient temperatures and experience long periods of dehydration.8

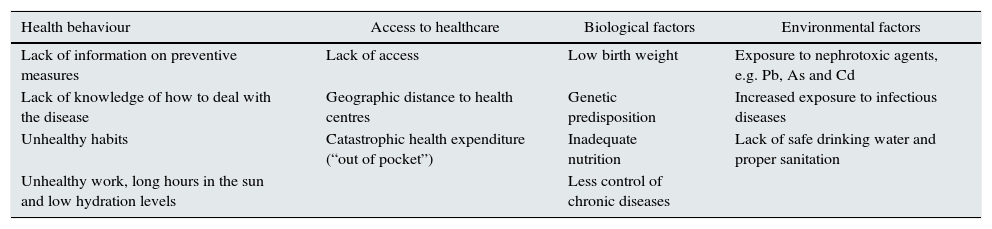

Poverty also adversely affects some of the most important social determinants of health, such as developing healthy habits, getting healthcare in a timely manner and suffering environmental exposure to nephrotoxic agents such as lead, cadmium and arsenic (Table 1).

Main mechanisms by which poverty leads to the development of chronic kidney disease.

| Health behaviour | Access to healthcare | Biological factors | Environmental factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of information on preventive measures | Lack of access | Low birth weight | Exposure to nephrotoxic agents, e.g. Pb, As and Cd |

| Lack of knowledge of how to deal with the disease | Geographic distance to health centres | Genetic predisposition | Increased exposure to infectious diseases |

| Unhealthy habits | Catastrophic health expenditure (“out of pocket”) | Inadequate nutrition | Lack of safe drinking water and proper sanitation |

| Unhealthy work, long hours in the sun and low hydration levels | Less control of chronic diseases |

Source: Adapted from García-García and Jha.11

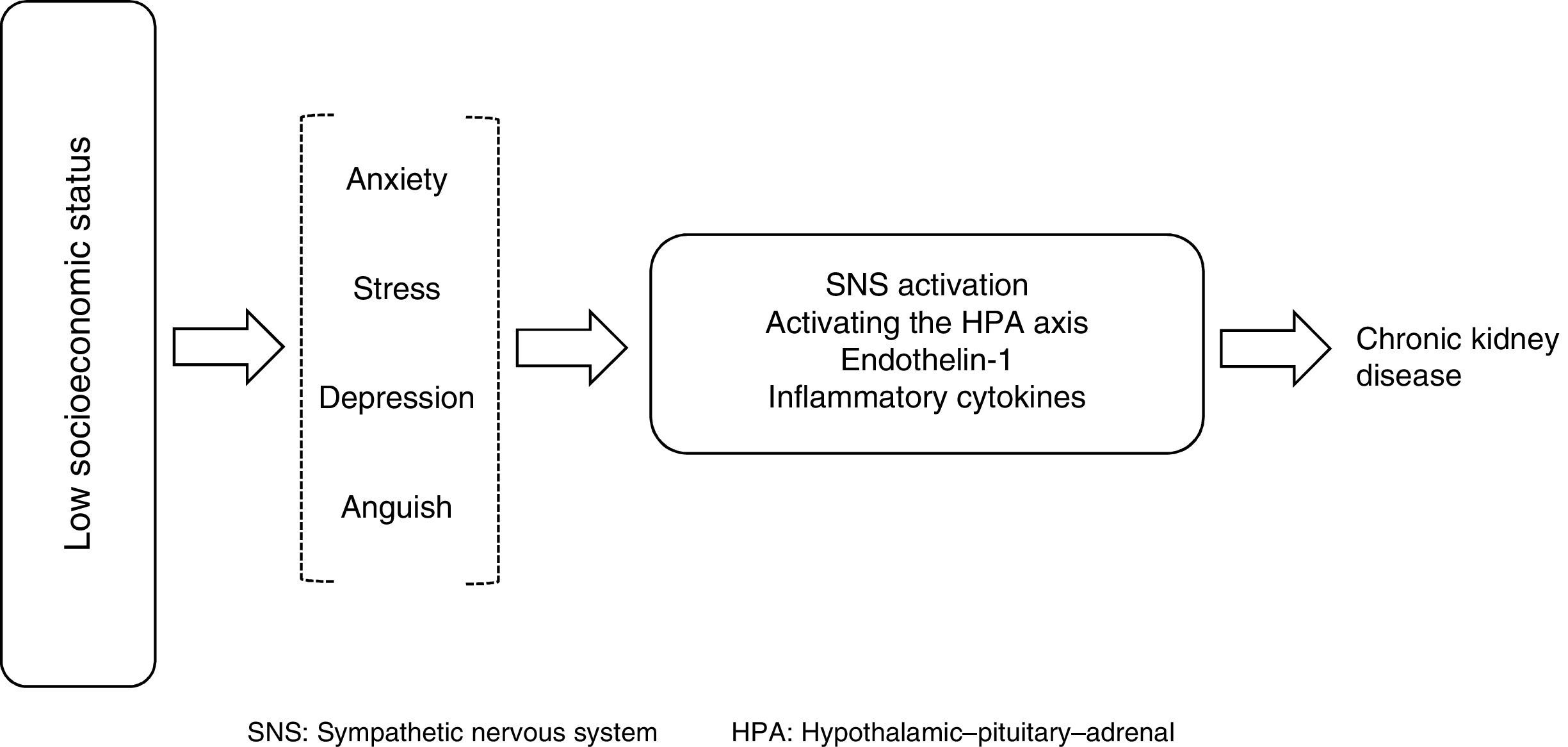

A higher prevalence of births with low birth weight promotes not only less development in terms of renal mass but also an increased risk of hypertension and CKD; the association of post-streptococcal GN with CKD has also been reported as a risk factor in some populations. Depression, anxiety and increased exposure to addictions also promote the activation of the sympathetic nervous system and an increased release of cytokines that can directly influence the pathogenesis of kidney damage (Fig. 1).9

An increased intake of sodium, sweetened beverages and foods with phosphorus has also been reported in this population. In addition, the chances of receiving proper treatment to slow the progression of kidney damage are lower in this population.10

A clearer understanding of the situations of vulnerable populations and risk factors in people in the lower socioeconomic strata might allow for designing better public health measures to reduce the burden of kidney disease in this population, since growth of national income per capita does not necessarily mean that the poorest members of society get better access to quality health services.

Further studies in industrialising countries and studies that provide more information about the pathophysiological mechanisms by which poverty is associated with a higher prevalence of CKD are needed.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Robles-Osorio ML, Sabath E. Disparidad social, factores de riesgo y enfermedad renal crónica. Nefrologia. 2016;36:577–579.