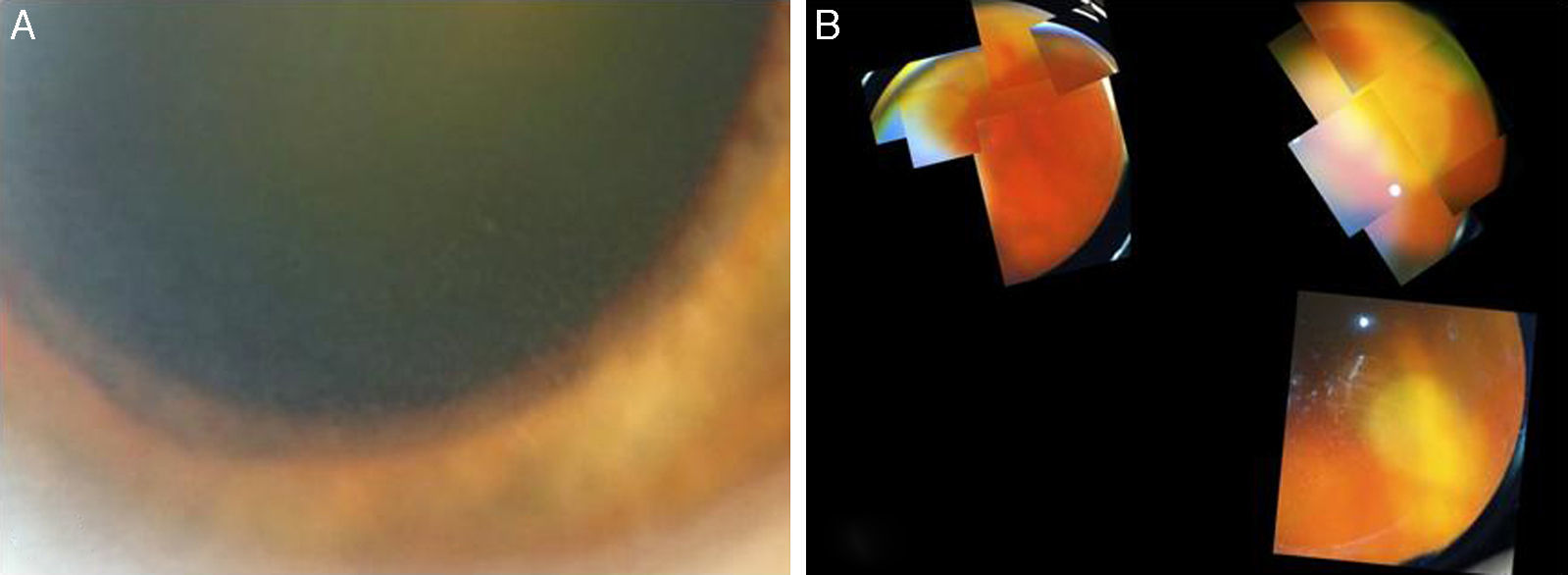

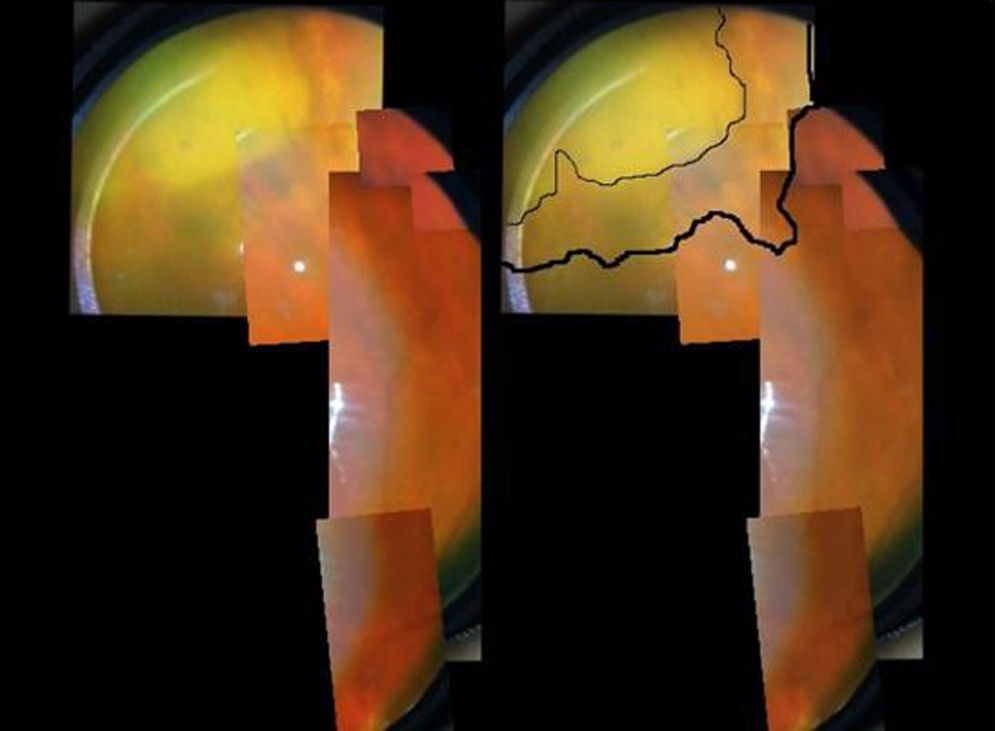

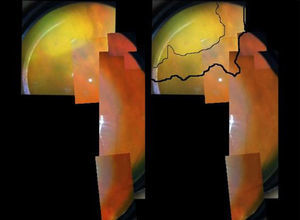

A 73-year-old male, with a kidney transplant in December 2006, and treated with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) 500mg/d and tacrolimus. In April 2012, he was admitted to another hospital for diffuse cutaneous varicella, which progressed favourably with oral acyclovir; source of infection unknown. In December 2012, he attended A&E at our hospital for one-week of history of floaters and decreased vision in the left eye. An ophthalmologic and funduscopic examination revealed retinitis of the affected eye with a visual acuity (VA) of 20/100 and an intraocular pressure of 18mmHg with a normal contralateral eye (Fig. 1A and B). PCR and viral serologic testing (IgG and IgM), and then a test for the varicella zoster virus (VZV), were negative (negative pre-transplant). A sample of aqueous humour from the anterior chamber for an analysis of viral DNA was obtained, and intravenous acyclovir was prescribed (the patient refused immediate intravitreal treatment). The patient's clinical progress was satisfactory, with rapid improvement after 11 days (Fig. 2), and initiation of a complete regression of lesions was evident. The PCR of aqueous humour confirmed that it was a VZV infection, and the rest of tests was negative. 360° laser photocoagulation of the retina was performed, while continuing with oral acyclovir. The patient was discharged 20 days after admission, with VA 20/32. Twelve weeks later, he presented with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, which, despite a successful replication by pars plana vitrectomy with scleral buckling and silicone oil, failed to achieve more than 20/200. Three years later, he has a VA of just light perception and residual inferior retinal detachment.

The incidence of VZV in the general population increases with age after, the age of 50. However, disseminated varicella is a rare presentation even in immunosuppressed patients, and when it occurs, it is usually during the first year after transplantation.1 This patient presented with clinical symptoms 9 years post-transplant with minimal doses of immunosuppression and without steroid therapy. His pre-transplant serology was negative, and so a primary infection due to varicella zoster was assumed; but he remained negative after 9 months of the cutaneous episode, which can be explained by the anergy of immunosuppression. To date, peri-transplant prophylaxis with acyclovir is not indicated in seronegative cases, but vaccination for VZV in waitlist patients, done at our centre since 2010, may reduce the incidence of this infection.

The time elapsed between the skin symptoms and the onset of retinopathy indicates virus latency in neurons. Primary VZV infection typically occurs in childhood, infecting the epidermal cells and causing the characteristic skin rash. Subsequently, the sensory nerve terminals of mucocutaneous tissue are infected reaching through axons the sensory roots of the dorsal root ganglia, where it remains dormant in neuronal bodies. Reactivation occurs with new virions in sensory neurons that migrate again through the axons to the epidermis (neuropathic pain and rash). It is known that cellular immune suppression plays an important role in this reactivation, such that these patients will present with VZV more often, with a prevalence between 3% and 14%.

Routine ophthalmologic examinations should be considered in patients with opportunistic viral infections. Retinal complications are rare,2 and amongst their most common causes is external progressive acute retinal necrosis (ARN), retinitis caused by cytomegalovirus (CMV) and toxoplasmosis. Necrotizing herpetic retinopathies are caused by VZV, herpes simplex virus I and II, CMV, and rarely, Epstein–Barr virus.3 Their most common presentations are decreased vision, pain and photophobia.4 On examination, multifocal yellowish-white patches are typical, which tend to coalesce in diffuse areas of full-thickness retinal necrosis. Other signs of ocular inflammation, such as vitritis, vasculitis, optic disc swelling, keratic precipitate and posterior synechiae, may accompany them. ARN is an ophthalmological emergency in which antiviral treatment should be started early, as it leads to blindness due to retinal scarring, retinal detachment or optic nerve atrophy. In addition, one-third of patients develop bilateral involvement within the first month of presentation.

The development of VZV in the transplant population has been associated to MMF5–7 This is due to viral thymidine kinase, which replaces the inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase inhibited by mycophenolate, thus allowing the cell to continue its life cycle. However, the specific involvement in this disease is not clear if compared with other immunosuppressants in clinical trials.8 In addition, MMF has been shown to play certain role in enhancing the antiviral activity of acyclovir.9 Thus the role of MMF in this type of viral infection or in this patient is not clear, especially when considering the low dose used. Clinical practice suggests that once disseminated disease presents, it makes sense to reduce the immunosuppressive burden, given the high morbidity and mortality of this disease.10

Please cite this article as: Morión Grande M, Martín-Gómez MA, Quereda Castañeda A, López Jiménez V, Cabezas Fernández T. Retinopatía necrosante herpética en trasplantado renal con mofetil micofenolato. Nefrologia. 2016;36:575–577.