Dear Editor:

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is the most prevalent symptomatic primary antibody deficiency, characterized by hypogamaglobulinemia, normal or decreased B-cell numbers and impaired antibody response leading to chronic and recurrent infections, mostly in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts1,2. However, a significant proportion of patients manifest features of immune dysregulation, including polyclonal lymphocytic infiltration, autoimmunity, enteropathy and malignancy3.

Secondary amylodosis is an extremely rare complication of CVID4, mostly reported in middle aged males5-7. This manifestation refers to the extra-cellular tissue deposition of serum amyloid A (SAA) protein fibrils with β-sheet structure, which could be due to chronic and recurrent infections in this group of patients8. The self-assembly by amyloid proteins cannot progress in the soluble condition of dissembled precursor proteins alone, while it is speeded up by seeding with preformed amyloid fibrils9 which described as «seeding mechanism». Also, enzyme inhibitory function against SAA proteins was confirmed in AA type of amyloid formation and deposition10. All reported CVID cases with amyloidosis had a sever status of infectious disease or underling complications like cor pulmonale, congestive hepatomegaly, bilateral bronchiectasis, severe respiratory failure7 and tuberculosis6. Recurrent infections could be considered as the main cause of the amyloidosis development; although recurrent infections could be as a consequence of inadequate IVIG therapy, long delay diagnosis can also prone patient to chronic and recurrent infections7.

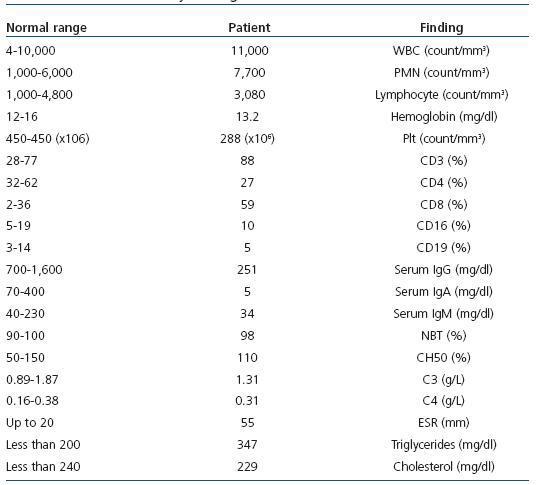

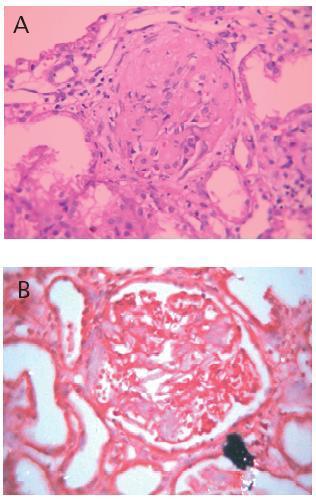

We report herein a 50-year old male with a history of recurrent respiratory tract infections and diarrhea from early childhood. The diagnosis of amyloidosis was made for this patient based on histopathological findings of renal biopsy, once he hospitalized due to edema and massive proteinuria at the age of 48 years. Renal fine needle aspiration biopsy revealed deposition of amorphous pink hyaline eosinophilic material in glomerulus, tubular basement membrane (TBM), interstitial area and vessel walls of arterioles; it was documented by green appearance fibrils under polarized light which stained and bind with Congo red (figure 1). As the patient experienced several episodes of infections, immunological studies were performed which showed significant decreased in all serum immunoglobulin levels, compatible with diagnosis of CVID (table 1). Regular hypo-osmolar intravenous immunoglobulin was started in addition to prophylactic antibiotics and cholchicin, which controlled his renal disease. Moreover, he has not experienced further episode of serious infection since last two years.

The clinical manifestations of amyloidosis are widely dependent to the type of deposited protein and amount of amyloid deposition. Variation in the clinical picture of amyloidosis is related to the type of precursor involved8,11. Moreover, the clinical features of amyloidosis vary by the organ affected; the most common organ involvement in CVID patients, which are complicated with amyloidosis, is kidney5,12. Gastrointestinal (malabsorption, perforation, hemorrhage and obstruction)6, joints (arthropathy)13, thyroid7, and gum were other sites which could be affected by secondary amyloidosis in CVID. Kidney organ function does not change with small amounts of AA amyloid deposition, while the prognosis of excessive deposition of AA renal amyloidosis is generally poor and potentially fatal14.

It is considerable that renal AA amyloidosis in CVID patients commonly presented with asymptomatic proteinuria, whilst nephrotic syndrome is present in more than one fourth of patients at the time of diagnosis15. Also, red blood cells count in urinary sediments and microscopic haematuria may present in CVID patients with the AA type, which more prominent than primary amyloidosis (AL type)15.

The incidence of AA amyloidosis could be increased with duration of the underlying disease condition and associated factors such as long delay diagnosis. The mean duration of inflammation before the diagnosis of amyloidosis is estimated about 8–14 years15. CVID patients usually experience several episodes of infections since childhood; it is expected that the patients had a history of many years inflammation without appropriate treatment, which is enough for progression of AA amyloidosis. The average age of reported CVID patients with renal secondary amyloidosis was 40.7 ± 10.9 years5-7, which is much lower than the age of other renal amyloidosis population (70.7 ± 12.0 years)15.

Glomerular deposition of amyloid substances in CVID patients had a significant differentiation from other individuals with renal amyloidosis. In these patients, immunoglobulins are not accompanied in intraglomerular deposition, while in other diseases associated with renal amyloidosis, deposition of IgG and C3 occurred at a rate of 60% and 45%, respectively. Furthermore, IgA deposition can be seen in 50-60% of cases with AA type9.

Control of the underlying inflammatory disease is the preferred therapy of AA amyloid, but patients who have diagnostic criteria of CVID should receive immunoglobulin replacement therapy. Administration of IVIG could dramatically reduce recurrent infections and subsequent complications in the patients with antibody deficiency1,2. Although the usual initial dosage for IVIG therapy is 300-400 mg/kg per month, higher doses of 600-800 mg/kg may be needed in subgroup of patients, especially in patients with bronchiectasis or chronic sinusitis. Nonetheless, IVIG may induce renal damage, especially in patients with preexisting renal insufficiency. Increased level of sucrose, blood viscosity and deposition of immune complex in renal tissue are the main causes of renal damage due to IVIG. Therefore treatment of CVID patients with amyloidosis is a subject of debate. However, high dosage of hypo-osmolar IVIG without sucrose (such as Gummunex or Octagam) is recommended for prevention of renal damage in addition with adjustment of dosage of antibiotics and colchicines. It is expected that new therapeutic strategies in addition to IVIG should be commenced in CVID-amyloidosis patients15. The biological agents such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) blocker, Etanercept, Iododoxorubicin and low-molecular-weight sulfates (Fbrilex) have been shown to be effective in treatment of AA-type renal amyloidosis9, which should be tried in CVID-amyloidosis patients as well.

Table 1. Patients laboratory finding

Figure 1. Renal glomerule with deposition of amorphous pink material proved to be amyloid by Hematoxyline, Eosin staining (A. X400) and special reacting to Congo-red stain (B. X400).