We describe a case of calciphylaxis with severe vascular calcification (VC) in a patient with CKD, after initiation of treatment for hyperparathyroidism. The patient made satisfactory progress with healing of the lesions, but mammography revealed the return of the severe VC.

Calciphylaxis or calcific uraemic arteriolopathy is a rare but significant cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic kidney failure (CKF). It consists of calcification of the media layer in skin arterioles and produces very painful lesions that begin as subcutaneous nodules and progress to ischaemia and necrosis with formation of ulcers. It has been linked to multiple factors, including hyperparathyroidism, hyperphosphataemia, use of vitamin D and calcium-chelating agents, calcification-inhibitor deficiency, proteins C and S, and use of oral anticoagulants, among other causes.1,2 VC is necessary but not sufficient for the disease to manifest itself clinically.3

VC and its aetiological mechanism is a subject of great interest, as it is an independent factor associated with cardiovascular mortality.4 Classically, it has been thought to be an irreversible process, and the aim of nephrologists has been to prevent it or at least slow down its progression.

Our case was a 54-year-old woman with CKD secondary to extracapillary glomerulonephritis with IgA deposits since 1993. In April 2011, she was started on treatment with paricalcitol for hyperparathyroidism, being previously treated with calcium carbonate for hyperphosphataemia. The creatinine clearance (Cr) was 20ml/m and PTH>2000pg/ml.

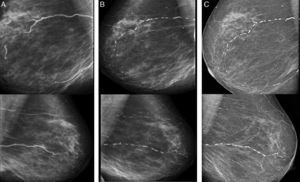

A year later, she was referred to the Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease (ACKD) clinic, where calciphylaxis was suspected due to the swollen and painful subcutaneous nodular pretibial lesions, which had developed into ulcers over the previous 5 months. Reviewing the patient's mammogram from 3 months earlier, severe linear calcifications could be seen in both breasts which were not apparent on her previous mammogram from 2008. Likewise she presented VC in other areas.

Kidney function had deteriorated (Cr 5.37, Cr clearance with 24h urine of 12.3ml/m with PTH>2000pg/ml, calcium [Ca] 9.2mg/dl and phosphorus [P] 6.2mg/dl) and it was decided to start haemodialysis and discontinue paricalcitol and calcium containing phosphate binders, She was started on cinacalcet, sevelamer, sodium thiosulfate (ST), antibiotics and opiates, and parathyroidectomy was scheduled. We decided not to take any biopsies due to the risk of infection of the lesions.5

Presently there is no standard therapy for calciphylaxis. Parathyroidectomy may be indicated, but does not always change the prognosis. Cinacalcet and bisphosphonates have demonstrated benefits, generally in combination with other treatments. Hyperbaric oxygen can also improve tissue hypoxia. ST has been associated with a rapid improvement in the pain and resolution of the ischaemic ulcers thanks to its antioxidant properties and it may also facilitate the elimination of vascular deposits of Ca.6

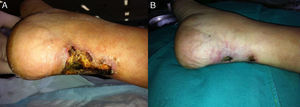

In our case, parathyroidectomy was performed a month later, with the development of hungry bone syndrome and the need for intravenous Ca and calcitriol supplementation for hypocalcaemia. After 5 months of treatment with ST and local wound care with silver patches, the ulcers healed (Fig. 1).

Since then, the patient's Ca levels have persistently remained below 8mg/dl, even with oral calcitriol supplementation at low doses during the first year after parathyroidectomy. Control of serum phosphate has been difficult. Three or more chelating agents: sevelamer, lanthanum and calcium acetate at full doses and, on occasion, aluminium based chelating agents have been required, despite having instructed the patient on how to take the chelating agents correctly and advise on foods with a better P/protein ratio. She has been on online post-dilution HDF with a minimum duration of 4h with good efficiency, with Kt/V and infusion volume within current recommendations.

Initially, our aim was to prevent the death associated with calciphylaxis, but also we set a longer-term goal, which was to prevent the progression of the VC. As can be seen on the mammograms, the change was remarkable, with striking regression of the calcifications which is sustained at present (Fig. 2).

We do not know which one of the various therapeutic actions applied brought about the regression of the severe VC presented at the start of haemodialysis. Correction of the hyperparathyroidism and discontinuation of vitamin D therapy, both of which could have been trigger factors, were probably decisive in the initial management. Starting haemodialysis and the treatment with ST also played an important role in the good calciphylaxis outcome. Control of P and Ca over the longer term are factors that we must not be complacent about.

As a general conclusion, we would emphasise the multifactorial approach in the treatment of calciphylaxis, without forgetting that, in terms of VC, the most important aspect is prevention: control of mineral metabolism; judicious use of vitamin D; and knowledge of precipitating factors in susceptible patients.

Please cite this article as: Ruiz-Calero RM, Azevedo LM, Bayo MA, Gonzales B, Cubero JJ. Regresión de calcificaciones vasculares en paciente con calcifilaxia. Nefrologia. 2016;36:569–571.