The pathogenesis of acute renal lesion in patients with malaria is not very well known, with endothelial damage and microvascular obstruction by the infected erythrocyte being suspected.1,2

Acute renal failure is quite common, and transient treatment with haemodialysis may be necessary. Generally speaking, no renal biopsy is performed and a mean recovery of 17 days is assumed.3 In some cases in which an anatomopathological study was available, minimal-change disease4 or collapsing focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis were diagnosed.5–8

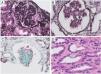

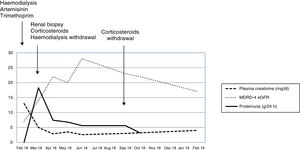

We present the case of a 43-year-old male, diagnosed in February 2018 in an African country with Plasmodium falciparum infection and treated with artemisinin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. He subsequently developed acute renal failure requiring replacement therapy with haemodialysis. More than one month after the diagnosis, and after agreeing to a renal biopsy due to the persistence of anuria and dependence on dialysis, the biopsy showed a collapsing focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis and an acute immunoallergic tubulointerstitial nephritis, with large intratubular crystals very specific to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Fig. 1). Treatment was initiated with three daily doses of 250 mg of intravenous methylprednisolone, followed by oral prednisone (1 mg/g/day), allowing the patient to recover and abandon the haemodialysis programme in a few days. In subsequent examinations, renal function improved progressively to an MDRD-4 eGFR of 20 mL/min, albeit in combination with a nephrotic range proteinuria (between 18.3 and 6.8 g/24 h). After reviewing all the cases published until then, we proposed continuing the treatment with corticosteroids in a regimen similar to the one used in the treatment of a primary focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis. The maximum improvement obtained was MDRD-4 eGFR 28 mL/min with a slight fall in proteinuria (5, 6 g/day). The treatment with corticosteroids was gradually reduced until it was discontinued after six months, without full recovery of renal function being achieved (Fig. 2).

Renal biopsy. A) Glomerulus with collapsing pattern in paraffin-embedded tissue with processing artefact (methenamine silver, ×200). B) Sclerosis of the glomerular tuft and hyperplastic podocyte, already in the shape of a Coptic cross in frozen tissue (methenamine silver, ×200). C) Glomerulus with heart-shaped collapse in frozen tissue (trichrome, ×200). D) Acute tubular damage and calcium oxalate crystals in tubular epithelium (H&E, ×200).

Hitherto, four cases of collapsing focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis related to a Plasmodium falciparum infection have been published. Two of them improved, a 12-year-old boy who required 28 haemodialysis sessions, but not corticosteroids,5 and a 37-year-old man who was given corticosteroids for six months, in addition to acute haemodialysis.6 The other two cases, a 72-year-old man7 and a 62-year-old woman8 required treatment with chronic haemodialysis. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is used for its antibacterial and antimalarial activity, as well as to avoid a potential artemisinin resistance, although in our case it was deemed responsible for an immunoallergic tubulointerstitial nephritis. The corticosteroid treatment produced a certain improvement and allowed the patient to leave the haemodialysis programme. Although the corticosteroid treatment was prolonged for several months, we did not obtain significant results. The patient is currently being followed up in the outpatient department, with an MDRD-4 eGFR of around 17 mL/min.

With this case, we emphasise the need to consider a diagnostic renal biopsy in patients with malaria and acute renal failure.

Please cite this article as: Alexandru S, Arduan AO, Picasso ML, Suarez LG-P, Saíco SEP, Sánchez MSP, et al. Fracaso renal agudo anúrico persistente en paciente infectado con Plasmodium malariae: la importancia de la biopsia renal. Nefrologia. 2020;40:571–573.