The living donor kidney transplant should be considered a priority option providing better quality of life and survival for those needing renal replacement therapy. To increase their number, both nephrologists and patients, should be informed more and better, offering this option compared with LDKT alternatives (dialysis or kidney transplant from a deceased donor). The clinical nephrology consultations or specific pre-dialysis are the space where in stages 3 and 4 of renal failure should be started on LDKT informational approaches. Later, when seeking more detailed information and/or evaluation of potential donors, this could be provided at times and spaces specifically reserved for awareness professionals with the use of brochures or Internet addresses. Information should focus especially on the additional benefits of pre-emptive LDKT, the risks of nephrectomy and long term controls for the donor. Finally, donor, recipient and family should know that the donation will only be justified and may be accepted if the studies of risk/benefit for the donor and recipient have been faithfully evaluated according to the highest ethical standards.

El trasplante renal de donante vivo (TRDV) se debe ofrecer como opción terapéutica prioritaria porque proporciona mejores resultados en calidad de vida y supervivencia para quienes precisan tratamiento renal sustitutivo. Para aumentar su número, es preciso informar más y mejor, tanto a nefrólogos como a pacientes, ofreciendo la opción del TRDV junto a las alternativas de tratamiento con diálisis o trasplante renal de donante fallecido. Las consultas de nefrología clínica o las específicas de prediálisis son el espacio donde en estadios 3 y 4 de insuficiencia renal se deben iniciar planteamientos informativos sobre TRDV. Posteriormente, caso de solicitar información más detallada y/o valoración de potenciales donantes, ésta se podría facilitar en momentos y espacios específicamente reservados por profesionales concienciados, siendo de ayuda la utilización de folletos informativos o direcciones de Internet. La información debería incidir especialmente en los beneficios adicionales del TRDV anticipado, los riesgos que supone la intervención de nefrectomía, y los cuidados y controles que necesitará el donante. Finalmente, donante, receptor y familiares deben saber que la donación sólo estará justificada, y podrá ser aceptada, si los estudios de riesgo/beneficio para donante y receptor han sido fielmente evaluados de acuerdo a los mejores estándares éticos.

INTRODUCTION

Kidney transplantation is the most cost-effective treatment for treating patients with stage 5 chronic renal failure (CRF).1 Moreover, living-donor kidney transplantation has better results.2,3 Therefore, it is considered as the best option that can be offered to patients that will need kidney replacement therapy in the short-term. However, the reality is that even patients that are seen in specialised nephrology consultations rarely receive full and up-to-date information on this therapeutic option.

Traditionally, it has been speculated that this technique has been poorly proposed in Spain due to the high number of kidneys available from deceased donors and the relatively short waiting times for deceased-donor kidney transplantation. Furthermore, in order to avoid needless harm, most nephrologists promoted protective methods and an attitude that they knew what was best for the patient. This made the LDKT rate drop below 1% in Spain, i.e. an almost token figure. On other occasions it was the patients with CRF or patients on the waiting list for a kidney transplant who were reluctant to ask family members or friends about donating. A significant percentage of them even refused to accept a kidney from a family member to protect them from the hypothetical risks to their health.4,5

Unfortunately, the kidneys that can be offered to most patients today are not perfect and the waiting times are not short enough to be able continue with this old-fashioned position. Therefore, practices have to change so that nephrologists can become more aware of this treatment and patients have more information and make their own objective decision. Thus, when kidney transplantation is not contraindicated, patients will consider LDKT as a low-risk procedure for the donor which is highly beneficial to the recipient.

In addition to providing patients with general information on LDKT, patients should also be informed about the advantages of pre-emptive transplantation, the risks of donating and the benefits of LDKT for the recipient.

WHEN AND WHAT TYPE OF INFORMATION

This is a key point and probably it is the most significant failing to explain why LDKT took so long to be incorporated into most transplant hospitals in Spain. Given that most patients have reservations or even are afraid of bringing up the subject of kidney donation as a treatment method, potential donors are usually the first to bring up the possibility of LDKT alone or with the patients present.6,7

New technologies that provide easily accessible information via the Internet must not be looked down on as they allow a growing number of people to find out about LDKT. Unfortunately, the best internet sites on living-kidney donation are from foreign hospitals or organisations, although many of them also offer multilingual information.9 In Spain, this information is currently available on the Spanish National Transplant Organisation (ONT) website16 and official websites of health foundations and services of the autonomous communities. However, this medium must be progressively expanded because a growing number of patients go to medical visits already armed with the latest information published on the internet, as already happens with other acute or chronic diseases.

In any case, if after implementing standard methods the overall predisposition towards LDKT cannot be improved in a transplant hospital, we should try to identify what might be holding back patients and health care providers and implement solutions objectively.11, 12

The difficulty of achieving an optimal level of information and awareness in religious, racial or ethnic minority groups, who visit public health services less often and are traditionally more reluctant to LDKT, must push us to try and implement personalised actions.13 Furthermore, the trend for larger families in these communities could a priori be seen as an additional advantage for LDKT.14 We must remember that kidney failure tends to progress faster in black patients due to genetic factors and worse blood pressure control. Furthermore, it has been found that donors from this community are at greater risk and recipients have worse outcomes. Several authors have studied the use of intensive education courses adapted to each minority group. They are carried out in their own homes and with the help of teachers from their own communities. These courses would convey the information better and gain greater trust in these communities by breaking down education and social barriers.15 Cultural mediators could work closely with the health care providers so that information on LDKT is passed onto these communities in the best possible way and they have a greater awareness of this therapeutic option.16

In addition to oral information provided during specialist visits or through the transplant coordination unit, there are other methods that could be useful. We could consider the possibility of showing videos, interviews, announcements, information on the operation and statements from LDKT donors and recipients in the transplant and clinical nephrology waiting rooms. This could be beneficial as patients and family members spend long periods of time there. It is important that patients and their family receive the preliminary information at the same time. Otherwise the patient may hide this therapeutic option to protect them or so that they are not pressured into it.

When patients and family members request more detailed information on LDKT, we believe that they should be offered a private visit, given the burden, speed and limitations that clinical visits have to work with in Spain. Therefore, in our hospital we arrange a visit in the Transplant Coordination Unit for patients and family members from predialysis or transplant care and from dialysis centres. Comprehensive information on LDKT is given for 30 minutes through the use of a brochure titled “Diez Razones para recomendar el trasplante renal de donante vivo” (ten reasons to recommend living-donor kidney transplantation), which goes through the process in a logical order (Figure 1). This brochure has been distributed to doctors, nurses, patients and family members who are interested in this therapeutic option since the end of 2008.17 We try to encourage all family members who are interested in this procedure to come to this first appointment with the patient. All of the 10 chapters of the brochure are explained in a relaxed manner without formalities during this first meeting. The patients and family members can then take it home with them. Before the end of the meeting, the demographic data and medical history of the people that might be interested in donating is collected, and everyone’s weight, height and blood pressure is measured.

Between 1 and 7 days later, the family members who showed an interest in donating are called to find out whether they wish to start basic medical tests: blood group, basic blood and urine analysis. Absolute discretion is guaranteed during this phone call if they decide not to continue with the tests.

Kidney donation usually comes from a person who is genetically related to the recipient, such as parents or siblings, although donations from other family members are also accepted. Other times the donor and recipient will have an emotional relationship but not genetic one, as in the case of husband and wives, couples or friends. In both situations the donors must fully understand that they will donate their kidneys without any outside pressure.

Although there are no universal rules, once kidney disease becomes chronic and kidney function is found to be decreased, whether it is stable or progressive, patients should be informed about the different kidney replacement therapies (KRT) that will be needed once their kidney function levels are close to being truly insufficient. Patients must then be assessed by nephrologists in predialysis or clinical nephrology visits where they will be told about the different KRT available. Among these therapies are the two dialysis treatments (peritoneal dialysis and haemodialysis) and the two types of kidney transplantation (living-donor and deceased-donor transplantation). The nephrologists have to take on this responsibility and not the transplant surgery teams, as they are who will be able to provide a better overall view of the kidney disease and present the different approaches in the best way possible, depending on the characteristics of the disease and the patient.18

This information is usually provided once the glomerular filtration rate reaches values close to 30ml/min. Specialists must stress the importance of preventive measures to avoid complications to other organs, the vaccinations and vascular accesses, which will be very important in the treatment of advanced chronic renal failure (CRF) patients. This information should be given in the late phases of stage 3 CRF and definitely once patients reach stage 4 CRF.

It is difficult for patients to take in this information and therefore, it should be dealt with delicately and doctors should take their time over it. It should never be presented as the end but rather as a change in strategy at the beginning of a new phase that will need a combination of different elements whether it is dialysis treatment or transplantation to restore the recipients’ kidney function. The specialist should present the different alternatives during the first conversation without going into too much detail. Patients should understand that the fact that there are many different options is a definite advantage for treating their disease and that all these options are available to them so that they can choose the one they prefer and available to them in later visits. In this way, patients will be able to process the information progressively and see a glimmer of hope when faced with a future that at some point is going to include more complex but necessary therapies to improve the length and quality of their life.

PRE-EMPTIVE TRANSPLANTATION

Kidney transplantation should be considered for all advanced CRF patients when there are no absolute contraindications. It offers a better prognosis for the length or quality of patients’ life whatever their age. Furthermore, if kidney transplantation can be performed without the patient having to start dialysis (pre-emptive transplantation), the benefits for the recipient are even greater. Pre-emptive transplantation could also be performed with kidneys from deceased donors but here we are faced with an ethical dilemma as this type of patient would be competing with others on the waiting list who may have been waiting a long time. Consequently, pre-emptive transplantation is only offered in most hospitals to patients who have the possibility of a LDKT, except in the case of paediatric patients and combined transplantations with the pancreas or liver, or the few AB blood group recipients.19

Pre-emptive transplantation can start to be talked about in advance, although it is not usually indicated until the glomerular filtration rate drops below 20ml/min (in Europe values below 15ml/min are considered to be more accurate).20 However, it is necessary to allow enough time to be able to complete the suitability tests on one or more family members so that you can assure that the patient will get the full benefit of pre-emptive transplantation and that it will be performed in time.21

One of the advantages of presenting the option of LDKT to patients with stage 3 CRF would be that in most cases the patients would receive this information along with their accompanying family members. Also, by offering this as the only means of KRT that avoids having to start dialysis, it would be seen in a much better light. Lack of communication between the three parties involved in the process (nephrologists, patient and family) has been found to be one of the most important obstacles explaining the low LKDT rates. The nephrologist does not consider the possibility of LDKT and patients do not speak to their families because it makes them feel awkward that their disease may be an added burden or risk for a family member. Therefore, it is often the family member accompanying the patient that brings up the question: “Doctor, could one of my kidneys be useful?”

If the LDKT option has not been brought up during the clinical nephrology visits, then this therapeutic option should definitely be dealt with during the specialised predialysis visits. Not doing this could be considered as medical malpractice.22 When close family members suddenly put themselves forward for donation, the nephrologist could offer to carry out a simple set of tests, including blood group, glucose, creatinine and basic urine test. A link is “formed” with these first steps that can be taken up again further along if there are no serious contraindications.

Pre-emptive LDKT must also be considered by nephrologists that look after patients with progressive deterioration of kidney function leading to kidney graft failure in less than a year. In fact, an increasing number of patients are starting dialysis due to kidney graft failure. These patients and their family members have generally had a very high quality of life after kidney transplantation, even though most of them have been on dialysis at some point for varying lengths of time. Therefore, the possibility of a pre-emptive living-donor retransplantation will more than likely be welcome and appreciated.

Lastly, we believe that pre-emptive LDKT should be considered as a priority option for paediatric patients diagnosed with CRF because the predisposition, suitability and outcomes are excellent when compared with any of the other options. In Spain there are certain autonomous communities where patients under 16 are given precedence for deceased-donor kidney transplantation.23

HOW SAFE IT IS FOR THE DONOR

If patients and family members go to the visit quite informed or have already made a decision, they should be informed in detail on how safe donating is and the type of tests used to find out whether LDKT is suitable. Firstly, nephrologists must make sure that they mention the inherent risks of anaesthesia, surgery and the possible intraoperatory and postoperatory complications. Special emphasis must be placed on discussing what effects living with only one kidney might have, including unusual risks such as severe trauma, infections or kidney stones, which may affect the function of their only remaining kidney. The experience in LDKT gained throughout the world over more than 50 years means that donating one of the kidneys is a very safe procedure. It also must be taken into account that the emotional benefits for many donors make up for the hypothetical risks involved.24 To reduce the possibility of nephrectomy-related complications, it is necessary to adapt the selection criteria for the donor to the most accepted protocols and to apply very high ethical standards so that no new complications arise.25 Consequently, a standard practice should be that the health care providers who perform the tests on the donors are not the same as those who perform the tests on the recipients, to avoid any conflict of interests.26,27

It is important that patients also come to these meetings to receive this information first-hand. Both patients and family members should be informed about the seriousness as well as the risk of having each of these complications (uncommon or rare). Where possible, reference should be made to the hospital’s indicators as, in the end, it is the risks associated with the hospital and its experience that will make them feel more or less secure about donating and transplantation. In general, these donors are at less risk of serious complications such as haemorrhage, infection or death than patients who undergo major surgery and general anaesthesia, as it must be taken into account that all the donors have been found to be in very good health. The tendency for the glomerular filtration rate to progressively decrease has not been found to be significant in the long term in any age group,28 the incidence of hypertension does not increase over time29 and life expectancy would be even higher than those who keep both kidneys. However, there is a bias in the group of donors studied as they have to undergo a considerable selection process and those with diseases or comorbidities are discarded.30

If donors are admitted at the same time as these first information sessions, an agreement could be reached so that these new families going through the testing process can get to know them and ask them about their actual experience with nephrectomy and LDKT.

Young women who are possible donors normally enquire about the possibility of becoming pregnant. No additional risks have been described during the pregnancy of patients having donated a kidney. However, blood pressure, weight gain and proteinuria must be closely monitored. In general, this is no different to what is normally recommended to any other pregnant women.31

Hospital stays are becoming even shorter with the current use of laparoscopic nephrectomy. In some series they have been as short as a single day, although in general 3-4 days is the norm. Patients are instructed to rest and avoid any physical exertion during the first two weeks. After this period, patients will normally be able to resume daily activities and return to work, depending on the job. It must also be stressed that donors will be able to do physical exercise without any special care or limitation 6-8 weeks after surgery.

Having analysed large donor series, the long-term safety of the donor may be considered secure if strict selection criteria continue to be applied. Nevertheless, extreme caution should be taken with elderly donors as the procedure has not been found to be as safe in groups of donors over 65.32 The demand for prospective national registers that include all living kidney donors should be implemented without delay.

In studies on kidney donors’ quality of life, donors are seen to be happier and they perceive their quality of life to be higher as they feel that their reasons for donating are continuously justified while the transplant continues functioning. In the case of married couples, in addition to an excellent graft survival rate, the additional advantages for the donor centre on the possibility of leading a more normal life with their partner without the limitations that dialysis or comorbidities associated with vascular access problems or kidney failure places on travelling.33

Lastly, we believe that offering specialised check-ups for life to all kidney donors is a good idea and makes them feel safer. This will provide advanced warning on the appearance of conditions such as weight gain, hypertension, diabetes or proteinuria, which might damage the only working kidney if left unattended.34,35

LDKT RISKS AND BENEFITS FOR THE RECIPIENT

The progressive increase in the use of LDKT is a sign that this therapeutic method is successful and that health care providers are increasingly relying on living donation. However, it may also reflect that there are fewer deceased-donor kidneys available and they are of worse quality.

Although kidney transplantation is the best way to treat chronic renal failure, patients must understand that it is not a definitive treatment when this option is explained to them. Very significant achievements have been made in reducing early graft loss as a result of acute rejection, primary graft failure or infectious complications in kidneys from both deceased donors and living donors. This is thanks to innovations and combinations in immunosuppressive drugs, treatment to prevent infections, advances in surgery and medical care. This has meant that the short-term and medium-term survival rates of transplanted kidneys have improved. However, the long-term survival rate has unfortunately not improved at the same rate. This information must be explained in detail to the parties involved because some patients and family members may be frustrated if they think of LDKT as a cure or they do not understand that they will be treated and monitored for their whole life. It is advisable to provide clear information on graft survival percentages, as well as graft survival figures found in autonomous and international registers. Transparency in this point is important and must be conveyed to avoid any disappointment.

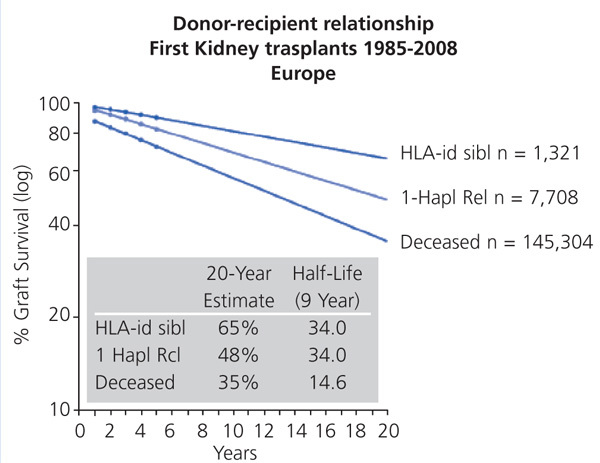

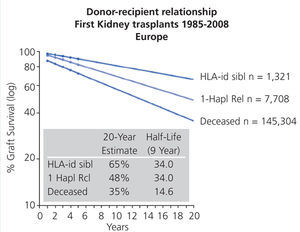

Professionals are unanimous in the belief that graft and kidney transplant patients have better survival rates when the kidney comes from a living donor than from a deceased donor (Figure 2).36 There are many reasons for this, for example it is a scheduled operation where the recipient and the donor are in perfect condition for the surgery, the optimal quality of the transplanted kidneys and the lower age of the recipients.

Immediate risks could arise from the operation if the recipient suffered a haemorrhage requiring even transfusions. Vascular, arterial or venous thrombosis may cause the kidney to never start working. This occurs in less than 5% of cases, although this percentage varies37 and is less likely in LDKT than in deceased-donor transplantation because both the donor’s and the recipient’s vascular tree is studied exhaustively before transplantation. Furthermore, any cases presenting probable high risk deformities are discarded.

Early acute graft rejection exists after LDKT, although this can be reversed with drug treatment. Furthermore, recipients start taking immunosuppressive medication several days before surgery and therefore, when they receive the organ, they have already reached a suitable level of immunosuppression.

One of the most important differences in living-donor kidney transplantation compared to deceased-donor kidney transplantation is the time elapsed between the kidney being removed and transplanted (cold ischaemia time). This time period is one of the major factors determining whether there is delayed graft function.38 Therefore, more than 95% of LDKT have immediate graft function. In the remaining cases a small number of dialysis sessions may be necessary in the immediate postoperative period. If this situation does continue, an early biopsy of the graft is recommended to find out the cause of the initial graft dysfunction (rejection or tubular necrosis).

The possible complications resulting from immunosuppression and the risk of infection will be logically the same as in the case of deceased-donor grafts. However, in some cases of related donors with excellent HLA compatibility a long-term, mild, immunosuppressive treatment may be used. The risk of losing the graft is increased if acute rejection occurs. Therefore, the most commonly used initial immunosuppressive treatment is the combination of steroids, mycophenolate and tacrolimus in combination with anti-CD25 induction therapy.

The recurrence of the initial kidney disease in the transplanted kidney is a problem with varying incidences. However, it is currently believed that it is the cause of graft failure in at least 8% of cases during a 10-year post-transplant period.39 Knowing the cause, history and evolution of kidney failure in the future recipient means that more precise information on the possible risks can be given. Living donation is advised against for patients who have a high risk of relapse, such as in the case of previous kidney graft failure due to this cause. Related donors must be assessed carefully, and a preliminary kidney biopsy may be necessary to discard familial kidney diseases that may have gone unnoticed (e.g. some cases of IgA nephropathy).40,41

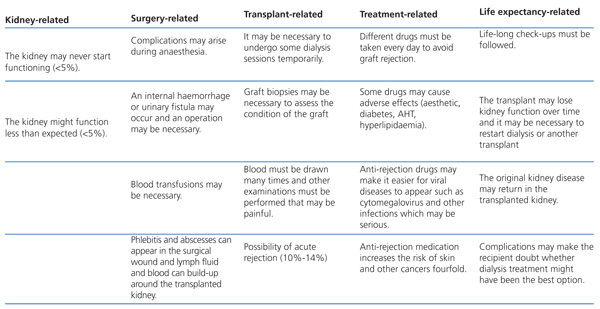

Table 1 is an adapted summary that can be used to round off the obligatory informed consent process so that recipients understand right from the initial assessment meetings the benefits of LDKT but without forgetting the risks.

Figure 1. Front cover of the brochure Diez Razones para recomendar el trasplante renal de donante vivo (Ten reasons to recommend living-donor kidney transplantation)

Figure 2. Graft survival and estimated graft half-life in European hospitals

Table 1. Summary of the main risks for the LDKT recipient