Currently due to the benefits reported with HHD,2,3 there is growing interest in home haemodialysis (HHD).1 In Spain, although the number of patients on HHD has increased in recent years, the percentage remains low,1 one of the main problems being that there is little familiarity with the technique4 and the fear of adverse events (AE) is manifested. For this reason, we considered it appropriate to analyse the AEs observed in the HHD unit of our Hospital from the beginning of the programme in March 2008 until June 2017.

We consider a serious adverse event (SAE) the one that required some type of emergency action by medical professionals, being automatically reported by the patient to the hospital, usually over the phone. Minor adverse events (MAE) were recorded by the patient in the haemodialysis form, and we conducted a retrospective analysis of these.

Since the HHD programme was started, we have trained 35 patients, 32 were able to move home and 3 did not pass the training (2 patients lacked self confidence and one had associated comorbidity).

Of the 32 patients on HHD: average age 57.6±13.1 years; Charlson index 4.1±1.7; 18 men, 14 women, 25% with diabetes mellitus.

Haemodialysis (HD) time/session was 149.5±16.1min; frequency 5.3±0.5 sessions/week; weekly time 791.9±94.8min; 14 NxStage systems and 18 conventional monitors; 20,034 days remaining at home (17,889 days/catheter and 2145 days/fistula).

In total, 4 SAEs, 0.072 events/patient/year (0.275 SAEs/1000 HD sessions).

Two episodes occurred in the same 49-year-old patient, after 7 and 9 months on HHD. The first was hypotension with loss of consciousness and recovery after being disconnected by the carer, who called the emergency services and the patient was transferred to hospital without requiring admission. The second episode was a new hypotensive episode with loss of consciousness and seizure, with the carer again being present. Hospitalisation was required to rule out the possibility that the patient had stopped taking antiepileptic medication. In both cases, the patient was ultrafiltrating a greater quantity than recommended by our unit.

The third episode occurred in a 43-year-old patient who had been on HHD for less than 6 months. It was a clot in the circuit at the end of the HD session, which reached the tunnelled catheter, causing full obstruction thereof. The patient was transferred to hospital where we removed the obstruction with urokinase and the patient was not admitted.

The fourth episode was a new hypotensive episode in a 72-year-old patient, without loss of consciousness, but a call to the emergency services was required without transfer to hospital.

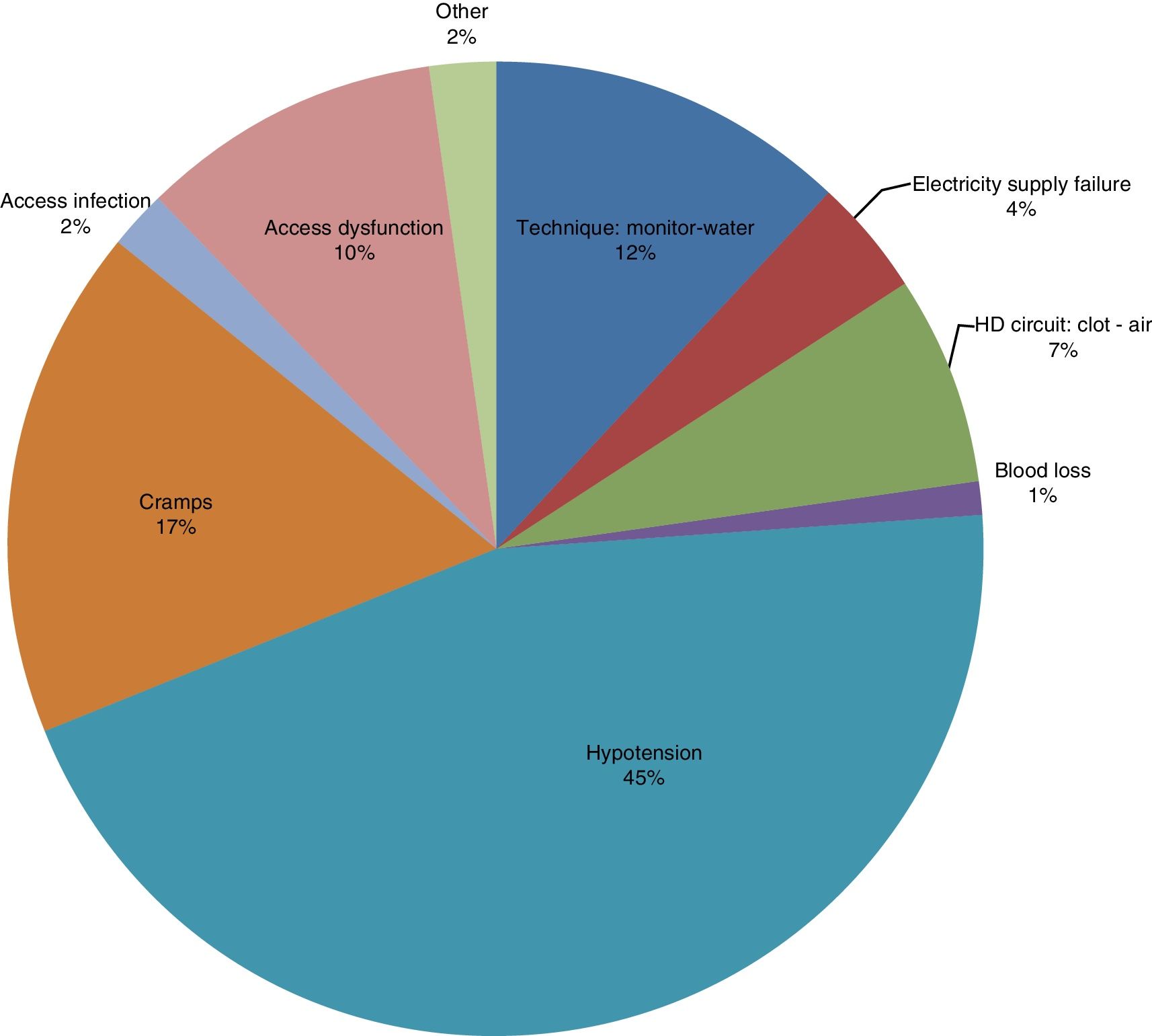

Regarding the MAEs, we retrospectively analysed 11,463 haemodialysis sessions (78.9% of the total HHD completed). In the remaining cases it was impossible for us to recover the information. We recorded 272 MAEs (Fig. 1), with a MAE rate of 23.72/1000 HD sessions.

Forty-one hospitalisations occurred (24.4% scheduled), 0.747 admissions/patients/year (19.5% due to cardiovascular causes, 26.8% due to infectious causes not related to vascular access, and 12.2% due to infectious causes related to vascular access). Six infection events related to the haemodialysis catheter, 5 required hospital admission (0.12 infections/patient/year) and none in the arteriovenous fistula. Regarding vascular access dysfunctions recorded as such by the patient on HHD sheets, 16 were due to catheter (1.59/1000 HD, 8 required hospital HD), 13 were due to fistula (8.95/1000 HD, 10 required hospital HD), relative risk 5.6 (2.7–11.6).

We did not record significant differences when we attempted to relate the MAE rates to patient age, Charlson [index], number of training sessions, and type of monitor used.

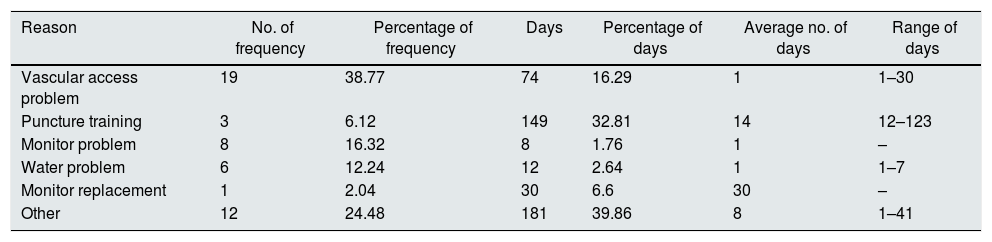

Patients required HD in a hospital unit, without considering admission episodes, for 454 days (Table 1).

Outpatient HD needs at hospital unit.

| Reason | No. of frequency | Percentage of frequency | Days | Percentage of days | Average no. of days | Range of days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular access problem | 19 | 38.77 | 74 | 16.29 | 1 | 1–30 |

| Puncture training | 3 | 6.12 | 149 | 32.81 | 14 | 12–123 |

| Monitor problem | 8 | 16.32 | 8 | 1.76 | 1 | – |

| Water problem | 6 | 12.24 | 12 | 2.64 | 1 | 1–7 |

| Monitor replacement | 1 | 2.04 | 30 | 6.6 | 30 | – |

| Other | 12 | 24.48 | 181 | 39.86 | 8 | 1–41 |

HD: haemodialysis.

We present a SAE rate similar to those described in the few existing series in the medical literature,5,6 although it depends what is considered as such, while Wong et al.5 describe it as a life-threatening event, Tennankore et al.6 consider it, like we did, as one requiring some kind of medical action. As for MAEs, data are also limited,7,8 again depending on what is considered a minor event, but our report is similar to previous publications.

We consider that in each HHD unit there should be an ongoing record of AEs that occur,9 if possible in real time, in order to establish the control and feedback methods for said events, to generate strategies and action protocols in order to minimise them. In our case, we set lower ultrafiltration limits, always at 10ml/kg/h. The exploration of the possibilities offered by telemedicine can provide great assistance in this regard.10

Furthermore, in all HHD units there should also be a series of dialysis stations that ensure sessions are available at times when the patient cannot do it at home.

We conclude that, despite being impossible to eradicate the possibility of AEs, the rate thereof is more than acceptable, making HHD a safe technique that can offer many benefits to patients.

Please cite this article as: Pérez Alba A, Reque Santiváñez J, Segarra Pedro A, Torres Campos S, Sánchez Canel JJ, Fenollosa Segarra MÁ, et al. Baja tasa de eventos adversos en hemodiálisis domiciliaria. Nefrología. 2018;38:452–454.