Haemorrhagic cystitis is defined as inflammation of the bladder mucosa that causes acute or subacute diffuse bleeding.1 It is caused by the inappropriate activation of proinflammatory cytokines, which destroy the mucosa and chorion through inflammatory apoptosis (pyroptosis), which leads to the opening of the microvessels to the bladder lumen. The main causes of bladder pyroptosis are bacterial or viral pathogens, ionising radiation or acrolein, a urinary metabolite of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide.2

The BK virus is one of the most important causes of late-onset haemorrhagic cystitis in patients undergoing haematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT). The evidence for the treatment of BK virus-associated haemorrhagic cystitis (BKV−HC) is limited, with cidofovir being one of the treatment options.3 Cidofovir is a cytidine analogue that demonstrates in vitro and in vivo activity against human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) because it suppresses replication by selective inhibition of viral DNA synthesis.4 The use of this drug in BKV−HC would be off-label.

This is the case of a 53-year-old man with no known drug allergies and with a personal history of dyslipidaemia and arterial hypertension.

The patient was diagnosed in 2016 with chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia (CML) and, after several cycles of chemotherapy (MAZE: amsacrine-azacitidine-etoposide; IDA-ARA-C: idarubicin-cytarabine), he underwent allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (Allo-HSCT) in May 2018.

Two months later, the patient went to the haematology day unit (HDU) to receive treatment with foscarnet against cytomegalovirus (CMV), acquired after Allo-HSCT, having reported haematuria accompanied by dysuria and burning over the previous few days. With these symptoms, the patient was admitted and diagnosed with haemorrhagic cystitis.

After several tests to discover the aetiology of the disease, copies of BK polyomavirus were detected in his urine. In light of these findings and after communication with the regional referral centre, it was proposed the use of intravenous cidofovir at a daily dose of 400mg/24h for 2 weeks (induction) and then every 15 days until virus eradication.

Renal function was assessed before starting treatment with cidofovir (>60ml/min) and the treatment start date was set: 03/07/2018. To decrease renal toxicity, probenecid was co-administered with cidofovir.

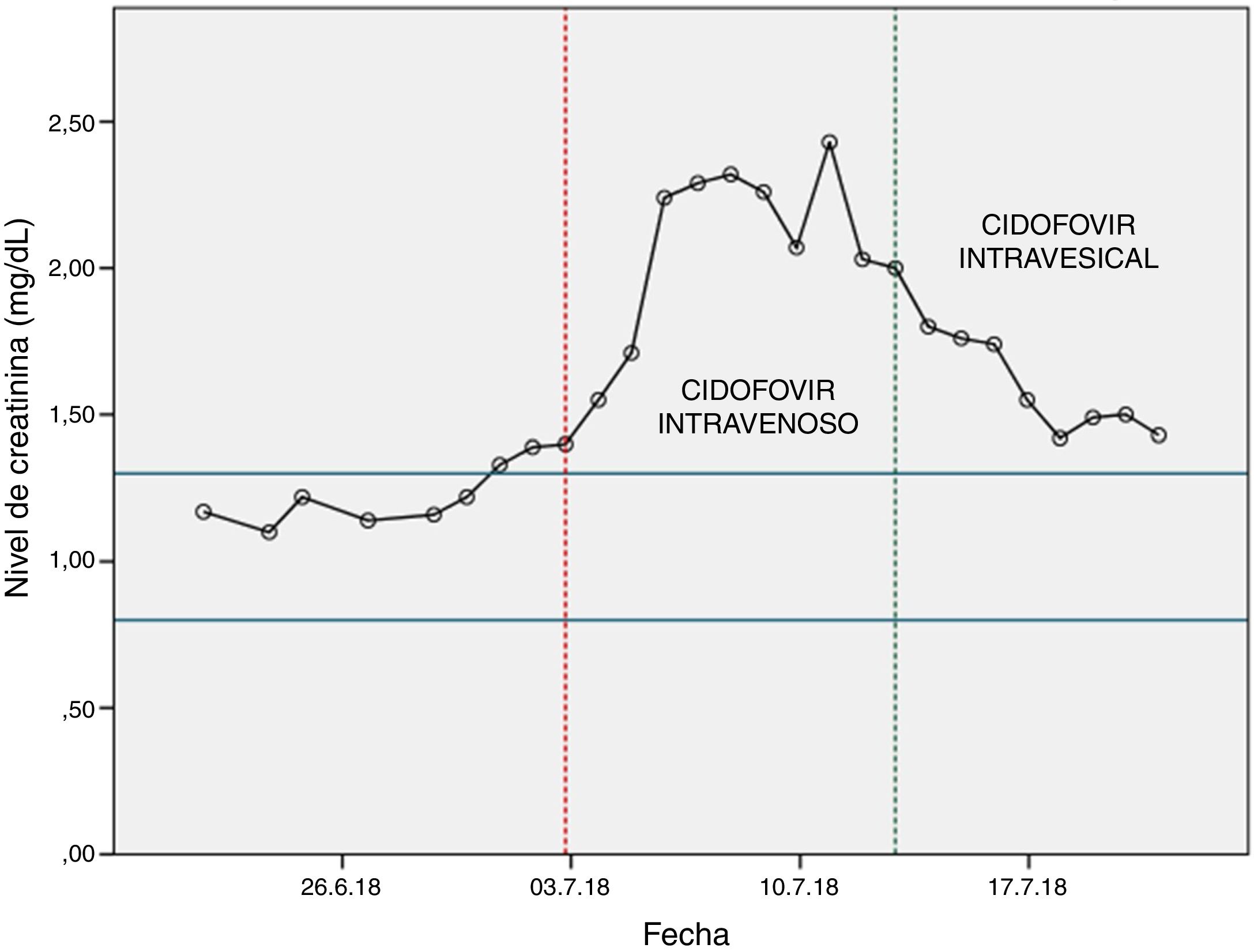

After the first dose of cidofovir, it was observed a significant increase in blood creatinine levels (Fig. 1), so the haematology unit contacted the pharmacy to find a solution to the problem.

As previously mentioned, the main toxicity associated with cidofovir is dose-dependent nephrotoxicity. The Spanish Agency of Medication ines and Health products (Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios — AEMPS) reports that the safety of cidofovir has not been evaluated in patients receiving other agents that are known to be potentially nephrotoxic (for example: tenofovir, aminoglycosides, amphotericin B, foscarnet, intravenous pentamidine, adefovir and vancomycin).4 In our case, the nephrotoxicity by cidofovir was exacerbated by the concomitant use of foscarnet, which could not be discontinued since the patient maintained positive CMV copies in plasma.

In light of the above, from the pharmacy department we conducted a literature search and found a systematic review that compared intravenous and intravesical administration of cidofovir in the treatment of BK polyomavirus-associated haemorrhagic cystitis after Allo-HSCT. It was found that the intravesical route gave a high rate of complete responses, but without renal toxicity.5

Based on these information, the use of intravesical cidofovir was recommended at 5mg/kg diluted in 60ml of 0.9% physiological saline solution and instilled for one hour into the bladder, with changes in posture (supine position, left lateral position, prone position and right lateral position) every 15min so that the drug could penetrate the entire mucosa of the bladder (nursing recommendation).

The first dose of intravesical cidofovir was administered on 13/07/2018, after which an improvement in renal function was observed (Fig. 1). After the first instillation of intravesical cidofovir, the urine PCR was repeated to detect copies of BK polyomavirus. The result was negative, so treatment with cidofovir was discontinued.

Our case shows that the use of intravesical cidofovir can be proposed as an effective alternative in patients with creatinine clearance ≤55ml/min (the limit for contraindication of intravenous cidofovir).

Please cite this article as: Ferrer A, Viña MM, Limiñana EP, Merino J. Cidofovir intravesical, uso en cistitis hemorrágica por poliomavirus BK tras un trasplante de progenitores hematopoyéticos: off-label. Nefrologia. 2021;41:79–80.