Leishmaniasis is a zoonosis caused by a protozoan parasite of the genus Leishmania.1 Risk factors include malnutrition, immunosuppression treatment and co-infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the latter being the most frequent association, occurring in most cases in a torpid and recurrent form.2,3 Renal involvement at both glomerular and tubular level has been described: it is usually mild and it cures with control of the infection.4,5 Here we present the case of a 45-year-old man with a medical history of hepatitis B virus infection in 2004 and HIV infection with normal CD4 levels (undetectable viral load) undergoing treatment with abacavir/lamivudine and doravirine. He had a history of opportunistic infection due to esophageal candidiasis and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. In addition, he had thrombophilia due to protein S deficiency on the anticoagulant acenocouramarol due to a history of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary thromboembolism.

The patient presented in the emergency room for dyspnea on moderate exertion and abdominal pain in the right hypochondrium for 2 weeks. He also presented with intermittent moderate fever for 3 months, arthralgias and nonspecific skin lesions on the upper limbs. Physical exam revealed hypertension (BP 157/103 mmHg, HR 80 lpm), predominantly bimalleolar edema and respiratory auscultation with bibasilar crackles. Analytics highlight deterioration of renal function, with serum creatinine of 2.42 m/dl (previous renal function was normal), hypocomplementemia of C3 and C4, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia with positive direct Coombs test, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. Urinary sediment showed dysmorphic red blood cells and proteinuria with an albumin/creatinine ratio of 1,537.6 mg/g. Antinuclear and anti-DNA antibodies were negative. Abdominal ultrasound showed normal-size kidneys and hepatosplenomegaly. Viral load for HIV and hepatitis B virus on serology were undetectable, with hepatitis C virus being negative. Cryoglobulins were positive, with a cryoprecipitate of 40% and immunofixation with data compatible with cryoglobulinemia type 2.

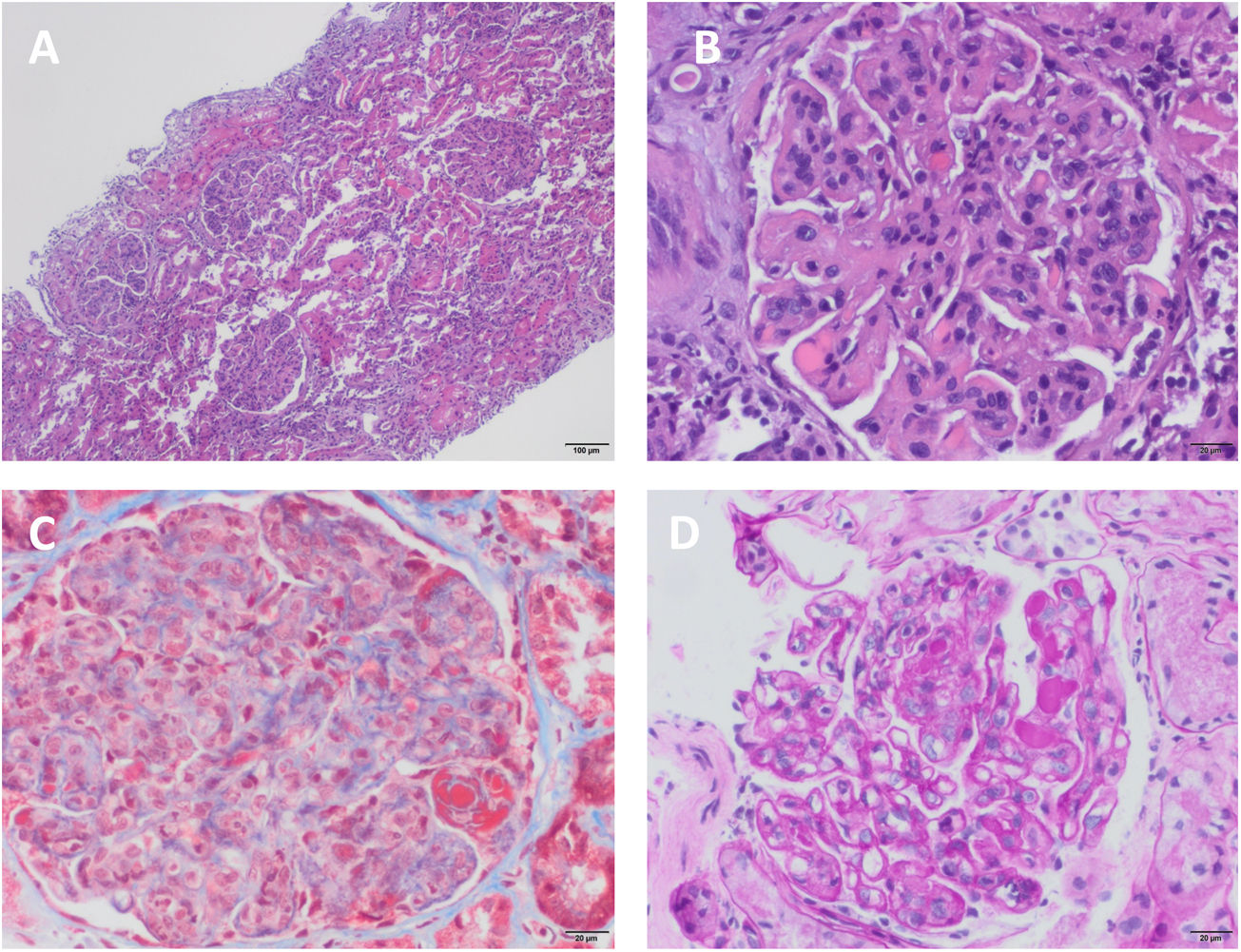

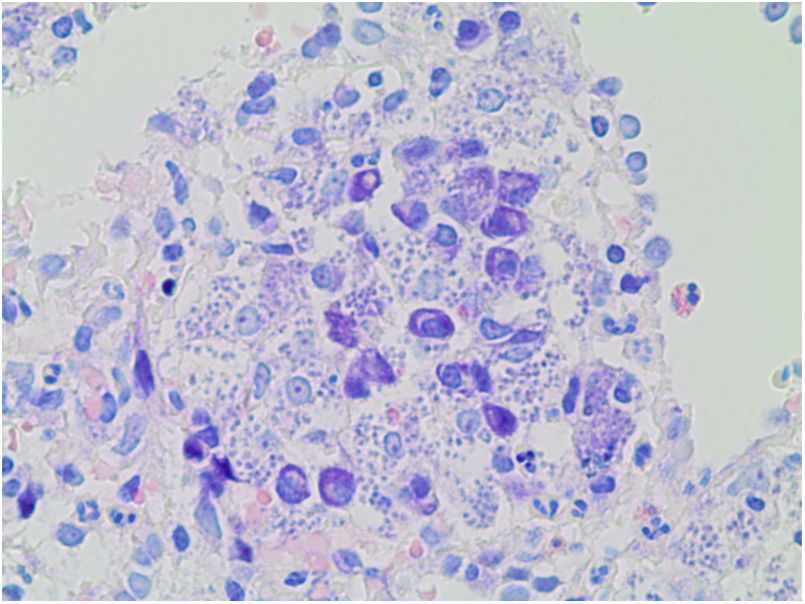

A percutaneous renal biopsy was performed, and 41 glomeruli were obtained, one of them with global glomerulosclerosis; the rest showed mesangial and endocapillary proliferation, with capillaries with double contour morphology. No crescents were seen. Tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis of 20%. Moderate lymphocytic infiltration. The immunofluorescence study showed mesangial and glomerular subendothelial deposition of IgM, IgG and C3. The diagnosis was glomerulonephritis with membranoproliferative pattern type I or glomerulonephritis mediated by immunocomplexes with membranoproliferative pattern (Fig. 1). Given the hypersplenism, it was decided to perform a splenic biopsy, showing abundant basophilic intracellular pathogens with the appearance of Leishmania (Fig. 2). In view of these results, treatment was started with liposomal amphotericin B at a dose adjusted to the glomerular filtration rate of 3 mg/kg/day. After 3 months of outpatient treatment the patient was asymptomatic, with improvement of renal function with creatinine of 1.2 mg/dl and without microhematuria and proteinuria.

Renal biopsy. (A) Mesangial and intracapillary hypercellularity with polylobulated appearance of the glomerular tuft and membranoproliferative changes, showing a "puzzle piece" appearance with the presence of hyaline pseudothrombi (H–E, ×4). (B) Mesangial and intracapillary hypercellularity with presence of inflammatory infiltrate and membranoproliferative pattern. Capillary thickening with "double contour" images and hyaline pseudothrombi (H–E, ×20). (C) Membranoproliferative changes and mesangial hypercellularity with intense red staining of hyaline pseudothrombi (Masson's trichrome, ×20). (D) Capillaries with thickened and rigid appearance, with double-contour or railroad track images (PAS, ×10).

The renal involvement described by Leishmania is very heterogeneous. The infection itself, the hemodynamic alterations derived from the disease (anemia, hypotension, hypovolemia), and even the treatment directed to the infection (amphotericin B) favor the development of renal lesions.6 Renal involvement by Leishmania is rare but is produced by the formation of autoantibodies and immunocomplexes, which lead to the activation of cytotoxic T cells and adhesion molecules.7 In our case, the patient started with deterioration of renal function with hematuria and proteinuria, hypocomplementemia and positive serum cryoglobulins. Serology for hepatitis C virus was negative, so it was suspected that another disease was associated cryoglobulinemia. A splenic and renal biopsy was performed at the same time, with the splenic biopsy providing the diagnosis of leishmaniasis and the renal biopsy the diagnosis of immune-mediated glomerulonephritis associated with this infectious disease. In a patient with constitutional symptoms, pancytopenia and renal lesion, clinician’s should consider leishmaniasis. The rapid initiation of specific therapy with amphotericin B for opportunistic infection by Leishmania led to a good evolution of the patient.