In our Universitary Hospital of Canarias we iniciated in May 2008 a induction therapy protocol for sensitized patients receiving cadaveric renal graft using intravenous immunoglobulins, plasmapheresis and rituximab plus immunosuppression with prednisone, tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil. We present the results of four patients. Everyone had anti-HLA antibodies rate (PRA by CDC) more than 75%, were on a waiting list during 4 to 17 years and follow-up time was 10-14 months after transplantation. Patient and graft survival in this period was 100%. Only one patient suffered a humoral acute rejection and another one cellular rejection, in both cases reversible with treatment. During the first year, no evidence of de novo donor-specific antibodies was detected. All patients had significantly reduced the CD19+ cells percentage after infusion of rituximab. Neurological symptoms suggestive of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy or serious viral infections after transplantation have not been observed. Additionally, no immediate side effects were observed after administration of medication. In summary, induction therapy by combining immunoglobulin, plasmapheresis and rituximab in hypersensitive patients allows the realization of deceased kidney transplantation with good results in the short and medium-term without serious side effects. It remains to know whether this success will continue in the long term.

En el Hospital Universitario de Canarias pusimos en marcha, en mayo de 2008, un protocolo de tratamiento de inducción para pacientes hipersensibilizados que reciben injerto renal de cadáver utilizando inmunoglobulinas intravenosas, plasmaféresis y rituximab más una inmunosupresión triple con prednisona, tacrolimus y micofenolato mofetil. Presentamos los resultados de 4 pacientes. Todos ellos presentaban una tasa de anticuerpos anti-HLA (PRA por CDC) superior al 75%, llevaban en lista de espera de 4 a 17 años, el tiempo de seguimiento posterior al trasplante fue de 10-14 meses y la supervivencia de paciente y del injerto en este período fue del 100%. Sólo un paciente sufrió un rechazo agudo mediado por anticuerpos y otro uno celular, en ambos casos reversibles con el tratamiento. En la evolución no se objetivó aparición de novo de anticuerpos donante-específicos. Todos los pacientes habían reducido significativamente el número de células CD19+ después de la infusión de rituximab. No se han detectado síntomas neurológicos indicativos de leucoencefalopatía multifocal progresiva ni infecciones virales graves después del trasplante y tampoco se han observado efectos secundarios inmediatos tras la administración de la medicación. En resumen, el tratamiento de inducción combinado con inmunoglobulinas, plasmaféresis y rituximab en pacientes hipersensibilizados permite la realización del trasplante renal procedente de donante cadáver con buenos resultados a corto y medio plazo y sin graves efectos secundarios. Queda por conocer si estos buenos resultados se mantendrán a más largo plazo.

INTRODUCTION

Recent induction treatments using the combination of plasmapheresis or immunoadsorption with intravenous immunoglobulins and/or rituximab has made it possible for patients at high immunological risk to undergo transplants with acceptable medium- and long-term graft survival rates.1-7 In May 2008, the University Hospital of the Canary Islands implemented an induction treatment protocol for hypersensitive patients, employing intravenous immunoglobulins, plasmapheresis and rituximab plus a triple therapy immunosuppressive regimen with prednisone, tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF). We present the results of applying this protocol to four patients at our centre.

METHOD

Patients were considered hypersensitive if they presented an anti-HLA antibody titre (PRA) above 75%, as measured by antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) and flow cytometry (Luminex). Requirements for performing a transplant on a hypersensitive patient at our centre are as follows: a) pre-transplant negative cytotoxicity crossmatch and b) negative virtual crossmatch test prior to the kidney transplant. i.e. abscense of all class I or II HLAs in the donor that have produced an alloresponse in the recipient at any time.

Immunosuppressive treatment consisted of:

1. Pre-surgery: oral tacrolimus 0.1mg/kg, MMF 2g.

2. Time of procedure: Intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone 500mg and first dose of ATG (thymoglobulin), 1.25mg/kg body weight, until completing seven doses over the following days. 3. MMF 2g/day. 4. Prednisone 1mg/kg/day during the first 48 hours, then reduced to 0.2mg/kg/day in the first month after transplantation.

Desensitisation treatment consisted of:

1. First day after transplant: rituximab 375mg/m2 , repeated with the same dosage on the seventh day.

2. Plasmapheresis on days 3, 5 and 7 post-transplant, with IV immunoglobulin infusion dosed at 0.5g/kg body weight following each session, with dose reinforcement of 1g/kg on days 10, 11 and 30 post-transplant.

During follow-up, plasma tacrolimus levels ranged between 10 and 12ng/ml in the first month, 8 and 10ng/ml in months 1 to 6, and 7 to 9ng/ml after the sixth month. We monitored CD19+/CD20+ lymphocyte populations and checked for any appearance of opportunistic infections using a PCR assay for CMV, Epstein-Barr viral serology, B-19 parvovirus and polyomavirus BK.8 Cytomegalovirus infection prophylaxis was carried out with gancyclovir/valgancyclovir, and Pneumocistis jirovecii prophylaxis was carried out with trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole. All patients gave their informed consent. In the event of a decrease in renal function not corresponding with an obvious cause, we performed a graft biopsy and C4d staining.9,10 Acute antibody-mediated rejection was treated with three daily plasmapheresis sessions and two to five sessions every other day together with immunoglobulin infusion (0.25g/kg) after each session (1g/kg after the last session).11 In addition, two doses of rituximab 375mg/m2 were administered a week apart.12-14 Severe cellular type rejection was treated with methylprednisolone bolus and ATG or OKT3.15 We present the results of applying this protocol to four patients at our department.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

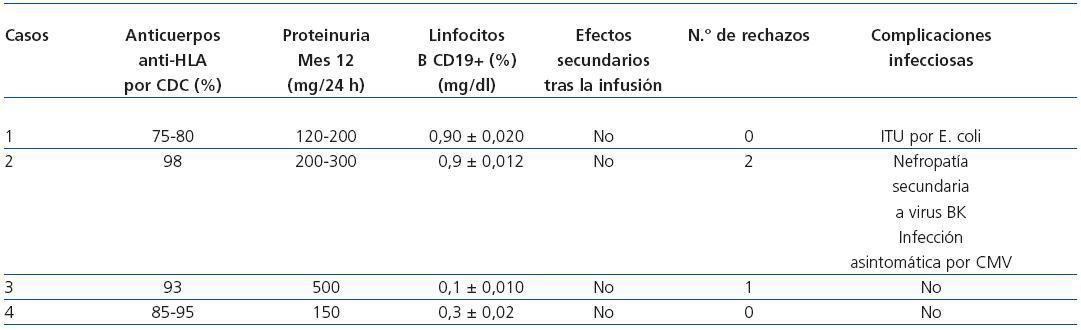

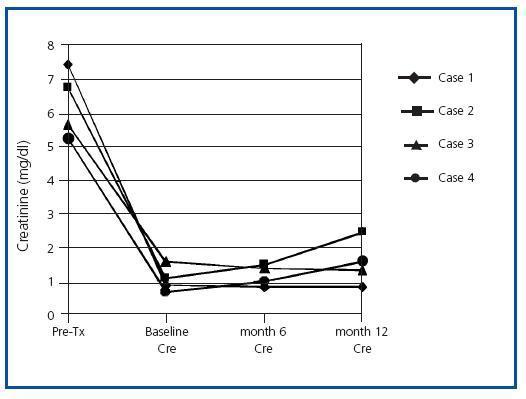

Male patient 46 years old with interstitial nephropathy and an eight-year history in haemodialysis (HD). He received two previous transplants in 2000 and 2004 with maximum circulating antibodies, and current anti-HLA I and II at levels of 75-80%. The patient lost the first graft four months after the transplant due to grade III acute vascular rejection, and the second graft was never functional. He developed haemolytic- uraemic syndrome and antibody-mediated rejection that required a transplantectomy a month after the transplant. The patient had received multiple transfusions, and the Luminex specificity testing for anti-HLA I antibodies was directed against antigens A1, B5, B5c, B35, B53, B51, B8, B15; specificity testing for anti-HLA II was directed against DR3, DR6, DR11, DR12, DR13, DR14, DR16, DR 51, DR52. The third kidney transplant was performed on 2 July 2008 from a 16-year old donor with antigen profile A24, A32, B40, B57, DR4, DR–. The receptor’s profile was A23, A68, B41, B47, DR1, DR4. The patient’s Luminex screening showed that he was not currently positive for specific antibodies against the new donor’s HLA antigens (negative virtual crossmatch). The patient followed the previously described induction immunosuppressant protocol and subsequent evolution was very favourable, with immediate renal function and a creatinine level of 0.9mg/dl upon discharge. Table and Figure 1 shows the evolution of renal function and other parameters during the follow- up period. The patient did not present immediate side effects when the drugs were infused. PCRs for CMV, BK virus and hepatitis viruses were negative throughout the period. The CD19+ count was 0.90 ± 0.02%.

Case 2

Male patient 40 years of age with type 1 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy and a 15-year history of HD. He had never received a kidney transplant, his maximum anti- HLA I antibody level was 100% and his current one was 98%. The patient had received multiple transfusions, and the Luminex screening did not detect anti-HLA II antibodies. The anti-HLA I specificities were directed against antigens B5, B5c, B15, B15c, B13, B7, B45, B12. The patient underwent a transplant on 27 June 2008. The recipient’s profile was A2, A24, B14, B27, DR3, DR4; the 43- year old donor’s was A2, A68, B39, B–, DR4, DR16. The virtual crossmatch was negative and the initial outlook showed immediate renal function with a creatinine level of 1.1mg/dl upon discharge (table 1 and figure 1). He did not present acute rejection episodes in the period after the transplant, nor were there immediate side effects from the medication. The PCR urine test for BK virus was lower than 10 copies/ml, and in plasma, lower than 22 copies/ml. The CD19+ count was 0.9 ± 0.012%. Four months after the transplant, the patient’s creatinine level had increased from 1.1 to 2.2mg/dl. In the graft biopsy, we detected signs of nephropathy due to stage B1 BK virus. The PCR test for BK virus in plasma showed 91,905,137 copies/ml, and in urine, 260,002,582,000 copies/ml. We decided to decrease immunosuppressants and begin compassionate treatment with cidofovir in four weekly doses of 0.5mg/kg/dose and four more fortnightly doses until March 2009. Creatinine dropped to 1.5mg/dl in the fifth month. In the sixth month after the transplant, the patient suffered another decrease in renal function and his creatinine levels rose to 2.2mg/dl. The second biopsy showed grade 1A acute cellular rejection with numerous plasma cells in the interstitium and occasional cytopathic effects on the tubular epithelium (SV40 antigen negative) and a negative C4d stain, with no evidence of kidney disease due to BK virus. The PCR test for BK virus in plasma was higher than 104 copies/ml, and in urine, more than 107 copies/ml. Given these findings, the patient was treated with MP boli, high amounts of intravenous immunoglobulins (0.5g/kg weight given in three doses) and received the fourth dose of cidofovir. The PCR screening and viral serology for opportunistic infections were negative, and creatinine was stabilised at 1.6mg/dl. In the eighth month after the transplant, he presented yet another decline, and creatinine levels rose to 3mg/dl. A third renal biopsy was performed which showed grade 1A acute cellular rejection; C4d stain was negative, and there was no evidence of kidney disease from BK virus (SV-40 immunostaining and viral PCR test of kidney tissue were negative). The patient was treated with three 250mg methylprednisolone boli and intravenous immunoglobulins (0.5g/kg of weight administered in three doses). Creatinine dropped to 2.1mg/dl. Ten months after the transplant, the patient presented an asymptomatic CMV infection, which was treated with valgancyclovir. The patient continued to have stable renal function 14 months after the transplant, with creatinine levels at 2.5mg/dl and proteinuria ranging from 200 to 300mg in 24 hours. Throughout the follow-up, PRA with a Luminex screening remained around 33-36%, maintaining the same specificity profile as before the transplant and without donorspecific antibodies appearing.

Case 3

Female patient 57 years of age with polycystic kidney disease and a 16-year history of HD. She received a transplant in 1991 and lost the graft due to anticalcineurin nephrotoxicity six months later. The level of anti-HLA I antibodies ranged between 68 and 93%. This patient had received multiple transfusions and undergone two pregnancies. The anti- HLA I specificities were directed against antigens A10, A29, A32, A33, B51, B52, B5c, B7c and B8 and specific anti-HLA-IIs were against DR4, DR6, DR10, DR13, DR51. The receptor’s profile was A2, A–, B44, B50, DR1, DR5. The kidney transplant was performed on 23 May 2008 with a graft from a 41-year old cadaver donor with a profile of A2, A30, B44, B–, DR1, DR7. The virtual crossmatch was negative. The patient did not initially receive the induction treatment described above since the transplant occurred before our protocol was put into practice. The induction treatment received was ATG, methylprednisolone and immunoglobulins dosed at 0.5g/kg, together with tacrolimus and MMF. The patient presented delayed renal function, so a primary biopsy was taken eight days after the transplant. We observed antibody-mediated acute rejection in a C4d+ stain and leukocyte margination along with acute cellular rejection (t1, i2) and mild tubular and vascular toxicity due to anticalcineurinic drugs. Treatment was initiated in the form of seven plasmapheresis sessions with intravenous immunoglobulin administered after each session, but evolution was not favourable and deterioration continued. A second biopsy with a C4d+ stain at 21 days also showed signs of antibody-mediated rejection and leukocyte margination along stage IIa acute cellular rejection (t1, v1, g1, i1) and tubular toxicity due to anticalcineurinic drugs. The patient received three methylprednisolone boli and two doses of rituximab. Subsequent evolution was very favourable; the renal function recovered, and the creatinine level was 1.6mg/dl upon discharge (Table and Figure 1). The CD19+ count was 0.1 ± 0.01%.

Case 4

Female patient 50 years of age with kidney disease of undetermined origin and a four-year history of HD. The maximum antibody level/current anti-HLA 1 level was between 85 and 95%. The patient was a multiple transfusion recipient with no previous pregnancies. She received a kidney transplant in 2004 which failed four months later due to acute vascular rejection and vascular thrombosis. Specific anti-HLA I antibodies were directed against antigens A1, A11, A23, A24, B7, B7c, B12c, B13, B15, B27, B37, B40, B41, B44, B45, B47, B48, B49, B60, B61, B63 and anti-HLA II antibodies were negative. The recipient’s profile was A2, A68, B7, B51, DR4, DR13. A few months before the second transplant, the patient had undergone desensitising treatment with plasmapheresis and intravenous immunoglobulin (2g/kg weight), but this did not decrease the antibody levels, so two doses of rituximab were added. After the treatment was complete, we did not notice a significant decrease in the antibody levels, but certain specific antigens disappeared, so a detailed so a detailed report was performed with the permissible class I antigens for renal transplant. On 27 September 2008, the patient received a graft from a 34-year old cadaver donor with a profile of A30, A–, B35, B-, DR13, DR–. She experienced immediate renal function, and creatinine levels by time of discharge had reached 0.7mg/dl (table and figure 1). She suffered no episodes of acute rejection or immediate side effects from the medication. The PCR tests for BK virus and CMV were negative in follow-up. The CD19+ count was 0.3 ± 0.02%. In July 2009, she presented decreased renal function with creatinine levels reaching 2.3mg/dl. The biopsy showed no signs of acute rejection, but rather, signs of tubular and vascular toxicity due to anticalcineurinic drugs. Kidney function increased partially, and creatinine levels reached 1.6mg/dl after optimising the anticalcineurin levels.

DISCUSSION

Today, few kidney transplant options exist for hypersensitive patients on the waiting list if they are not previously given desensitising treatments or strong induction therapy. In this respect, high doses of intravenous immunoglobulins have managed to reduce the level of circulating antibodies, but despite their effectiveness, many patients only respond partially, and the effect varies from person to person.4 Other researchers have shown that plasmapheresis can decrease circulating antibodies,5 but there is normally a significant increase in their titre levels once the sessions have been completed. Therefore, this technique is now considered a complement to the use of immunoglobulins for decreasing antibody levels. Likewise, rituximab has also been shown to have a beneficial effect when combined with immunoglobulins and plasmapheresis to reduce anti-HLA antibodies and treat antibody- mediated rejection.4,11-13 In any case, the strategy of combining these measures may well be the best treatment choice for these patients, particularly when there is early detection of acute antibody-mediated rejection through histological or serological techniques. In our immunology laboratory, the patients’ pre-transplant studies are systematically carried out following two approaches: periodic monitoring of circulating antibodies, and completing crossmatch testing prior to the transplant. The main goal of monitoring circulating antibodies is to measure PRA and identify specific antibodies in order to evaluate the patient’s immunological risk and interpret a crossmatch. We do so using ADCC and Luminex. The latter technique allows us to screen in order to find out if the patient has anti-class I or anti-class II antibodies and determine their specificity against purified HLA antigens.16,17 All patients in our study presented PRA levels measured by ADCC that were higher than 75%, and had been on the waiting list between 4 and 17 years; the mean follow-up time after the transplant was 10- 14 months, and patient and graft survival during this period was 100%. Only one of the patients experienced an episode of acute antibody-mediated rejection, and this was the patient who had not received the proposed induction procedure. Another patient experienced an immunological graft dysfunction, but it was cellular and not humoural, and both cases resolved with treatment. During patient follow-up, we did not see any de novo donor-specific antibodies appearence in our patients. Although PRA levels were similar to those during the pre-transplant period in three of our patients, they decreased significantly in the case 2, reaching 33%.18 All patients had lowered their CD19+ cell counts after the rituximab infusion, reaching average percentage of 0.56 ± 0.02% of the total of B-lymphocytes. This demonstrates the powerful depleting effect these drugs have on B-lymphocytes over the medium term. To date, we have observed no neurological symptoms that would indicate progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy or severe viral infections after the transplant.19,20 Nor did we observe immediate side effects following drug administration, which is probably due to the premedication used before the infusion. In summary, combined treatment with high doses of immunoglobulins, short plasmapheresis sessions and low doses of rituximab as an induction in patients with high PRA levels allows us to perform cadaver-donor kidney transplants with good short- and medium-term results, and without severe side effects from the immunosuppression. It remains to be seen if these good results would be maintained over the long-term without undesirable infectious or tumour side effects. Longitudinal studies over the long term will shed light on these questions.

Table 1. Evolution of patients' analytical and clinical parameters

Figure 1. Creatinine evolution during the first year after renal transplant. Creatinine (mg/dl).