Our patient is a 70-year-old woman with chronic kidney disease secondary to polycystic kidney disease. She began haemodialysis in 1995 and received the first deceased-donor kidney transplant (DDKT) in 1997; the graft was lost 15 days later due to acute rejection, followed by removal of the graft. In 2004, a second DDKT was performed, and a kidney graft was implanted in the left iliac fossa with end-to-side anastomosis of the external iliac artery with the renal artery; as induction immunosuppressive therapy, she received sequential quadruple therapy with basiliximab, prednisone, mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus. The patient became stabilised with creatinine levels of 2mg/dL. Her medical history also included type 2 diabetes mellitus, moderate-severe mitral insufficiency and severe peripheral arterial disease with bilateral femoropopliteal obliteration diagnosed in 2007.

After kidney transplantation, blood pressure was controlled with an α-blocker until 5 months prior to the current episode, when she presented at office visits with poor blood pressure (BP) control of 190/90mmHg, Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) showed a mean 24h BP of 166/89mmHg and a riser pattern despite treatment with 3 drugs (α-blocker, ß-blocker and diuretic). Treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors was initiated, and 2 weeks later renal function decreased with creatinine levels of 3.2mg/dl; this drug was withdrawn and renal function improved.

The patient reported symptoms that had been progressing over a week period, including progressive dyspnoea, oedema and a weight gain of 5kg. Upon hospitalisation, she presented a BP of 180/90mmHg. Physical examination detected bibasilar crackles, systolic murmur in the mitral area, absence of bilateral dorsalis pedis pulses, pitting oedema and murmur in the right groin. The workup upon admittance showed serum creatinine 3.1mg/dL; chest X ray presented signs of heart failure.

The oriented diagnosis was biventricular heart failure in the context of a hypertensive crisis, and treatment was initiated with nitro-glycerine and endovenous furosemide, which resulted in improvement of both BP and heart failure. Afterwards, oral antihypertensive treatment was renewed and ACE inhibitors were initiated. 24h after having begun treatment with ACE inhibitors, the patient presented oliguria and a serum creatinine of 3.9mg/dL. Once again, the signs of heart failure worsened, which required the initiation of ultrafiltration. Doppler ultrasound of the kidney graft demonstrated that size and corticomedullary differentiation were preserved; the intra-arterial flow had flat waves and a resistance index (RI) of more than 0.54, while main renal artery velocities were within normal ranges.

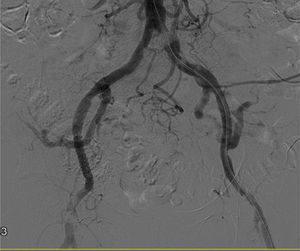

Despite the fact that Doppler ultrasound, repeated on 2 occasions, did not suggest stenosis of the renal artery, we decided to perform an angiography. The study detected obliteration of the distal portion of the left common iliac artery (Fig. 1), with permeability of the rest of the iliac axis and of the artery of the renal graft. After pre-dilatation, a stent was inserted in the area of the obliteration, with almost complete recovery of the vascular calibre (Fig. 2).

Immediately after, the patient presented polyuria of 6L in 24h and excellent BP control. Moreover, 24h later, renal function had improved (creatinine 2.5mg/dL), so no further ultrafiltration sessions were necessary. At the follow-up visit one-month later, the patient was normotensive with 3 drugs (α-blocker, ß-blocker and diuretic) and renal function had improved, with serum creatinine levels of 1.85mg/dL.

Discussion: As the age and survival of kidney transplant recipients increase, atherosclerotic disease, which is the Achilles heel of renal disease, is more prevalent and severer among our patients.

Renovascular hypertension especially affects patients with previous vascular disease. Clinical manifestations usually include difficult-to-treat hypertension and deterioration of renal function due to the hypoperfusion and activation of the renin–angiotensin system. Secondarily, patients may present water retention, oliguria and episodes of heart failure.1

In the literature, there are numerous cases of renal artery stenosis described in transplanted patients, but there have been only scarce reports of iliac artery stenosis1–4 as a cause of renovascular hypertension.

Both renal artery stenosis of transplanted kidneys as well as the stenosis of the iliac arteries are potentially reversible entities and have good therapeutic results with percutaneous angioplasty.5,6

With the case that we have presented, our intention is to call the attention of the need to assess the permeability of the pre-transplantation aorto-iliac axis. Furthermore, although stenosis of the iliac artery is an uncommon cause that is undetectable with Doppler ultrasound, when there is high clinical suspicion it should be ruled out as it is a reversible cause of hypertension and kidney function decline in transplanted patients.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: González-Cáceres AP, Bancu I, Juega-Mariño JF, Cañas-Solé L, Bonet J, Lauzurica R. Obliteración de la arteria ilíaca como causa de hipertensión renovascular en el paciente trasplantado renal, un diagnóstico difícil y poco frecuente. Nefrologia. 2015;35:413–414.