To the Editor,

Haemolytic-uraemic syndrome (HUS) is a microvascular disorder defined by microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopenia, which mainly affects the kidneys and is characterised by haematuria, oligoanuria and kidney failure.1 There is a group of patients (5-10%) with atypical HUS usually associated with immunosupressor users, oral contraceptive users, pregnancy and postpartum. These cases tend to have a poor evolution and a high mortality rate.2

We present the case of a 32-year-old woman, with no relevant history of disease. She was 32 weeks pregnant, attending an obstetric check-up and presented oedema on the face and limbs, blood pressure 220/140mmHg and proteinuria 3g/l. She was diagnosed with preeclampsia.

She is referred to the nephrology department due to poor hypertension control (HTN), despite treatment with alpha-methyldopa and labetalol. After foetal maturation, an emergency C-section is performed, with initial improvement of the HTN and oedemas.

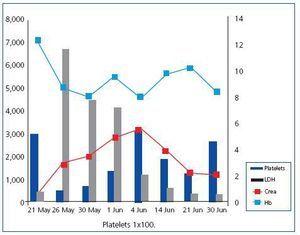

Three days later, the patient complained of migraine and blurred vision along with HTN. The blood work shows kidney function deterioration and haemolysis: creatinine 3mg/dl, haemoglobin 8.7g/dl, platelets 45,000/ml, haptoglobin <0.24g/l, bilirubin 1.5mg/dl, LDH 6,686U/l and 6% schistocytes in peripheral blood smear.

This data reveals a thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) related to the pregnancy. Its appearance in the postpartum and the manner that it generally affected the kidney, lead us to diagnose the patient with HUS and commence early treatment with plasmapheresis (PP) and prednisone (1mg/kg/24h).

The patient worsened, presenting acute pulmonary oedema during the first PP treatment, which meant that she had to be admitted into the Intensive Care Unit to start haemodialysis. Given that the haemolysis persisted, an abdominal ultrasound is performed to rule out any process that may cause the symptoms to perpetuate.

The ultrasound showed that there were no placental remains, but a subcutaneous haematoma from surgical wound is visible. It was drained and empirical antibiotic treatment with clindamycin and levofloxacin started. The patient showed progressive analytical and clinical improvement (Figure 1).

Fifteen PP sessions and intermittent HD were needed until remission of haemolysis and improvement of kidney function. On discharge, the patient presented creatinine 2mg/dl, MDRD 40, low proteinuria (0.5g/l) and adequate BP control with quadruple therapy (ACE inhibitors, calcium antagonists, diuretics and alpha blocker).

In the six-month check up, kidney function was normal with minimum proteinuria and treatment is maintained only with an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).

There are two major entities characterised by pregnancy-related TMA: severe preeclampsia (generally with HELLP syndrome) and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)-HUS. It is difficult to differentiate between these entities given that various clinical and laboratory findings overlap. This means that it is important for a precise diagnosis to be made as early as possible, given that the medical treatment and the complications involved can de different.3

TMA pathogenesis during pregnancy or in the puerperium period is unknown and in recent years studies have found that mutations in various genes involved in regulating the complement would cause tissues to lose their protective capacity (factor H 20% and factor I 15%). Situations associated with complement inflammation and activation, such as pregnancy or infections (in our case, subcutaneous abscesses), could trigger or perpetuate the process in genetically predisposed people. The final aspect would be the microvascular damage and platelet activation with multiple organ injury.4

Plasmapheresis has proven to be the therapy of choice, improving survival up to 80-90% and achieving good kidney function evolution results.

With this case, our aim is to stress that good results can be achieved for this disease with early treatment and to emphasise that it is essential that secondary processes that could perpetuate symptoms are diagnosed and treated.

Figure 1. Graph of the analytical evolution of the symptoms.