Sickle cell nephropathy is one of the complications of sickle cell disease (SCD); this is due to the polymerization of deoxygenated hemoglobin S in the renal medulla, a place of special physiological conditions (hyperosmolarity, hypoxia and acidosis)1,2 which contributes to the typical obstruction of vessels.3

Chronic renal failure and proteinuria are the risk factors associated with increased mortality in these patients.4 Albuminuria is the initial marker of SCD associated glomerulopathy, the most frequent expression of which is focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSG).5,6 Renal biopsy is indicated if glomerulopathy is suspected.

We present the case of a 30-year-old white male, with a history of homozygous sickle cell disease that was treated with hydroxyurea and deferasirox, he develops 1–2 annual crises, with no renal repercussions until present. Smoker of 3 cigarettes per day.

The patient was sent for consultation in relation of proteinuria of 2.75g in 24h (albuminuria: 1.5g/24h). The urine density was 1006, pH: 5.5, proteinuria 100mg/dl and a normal sediment. Renal function was normal (Cr: 0.7mg/dl and MDRD>60ml/min); Hb: 10.8g/dl; Hto: 30% (TSI: 80%, folic acid: 8.2ng/ml; VitB: 570pg/ml) and CRP: 6.6mg/l. The expanded study with autoimmunity and hepatitis C and B viruses as well as HIV is negative. In abdominal ultrasound, the kidneys do not have morphological abnormality and the spleen was small with diffuse increase of echogenicity suggesting fibrosis after repeated infarctions.

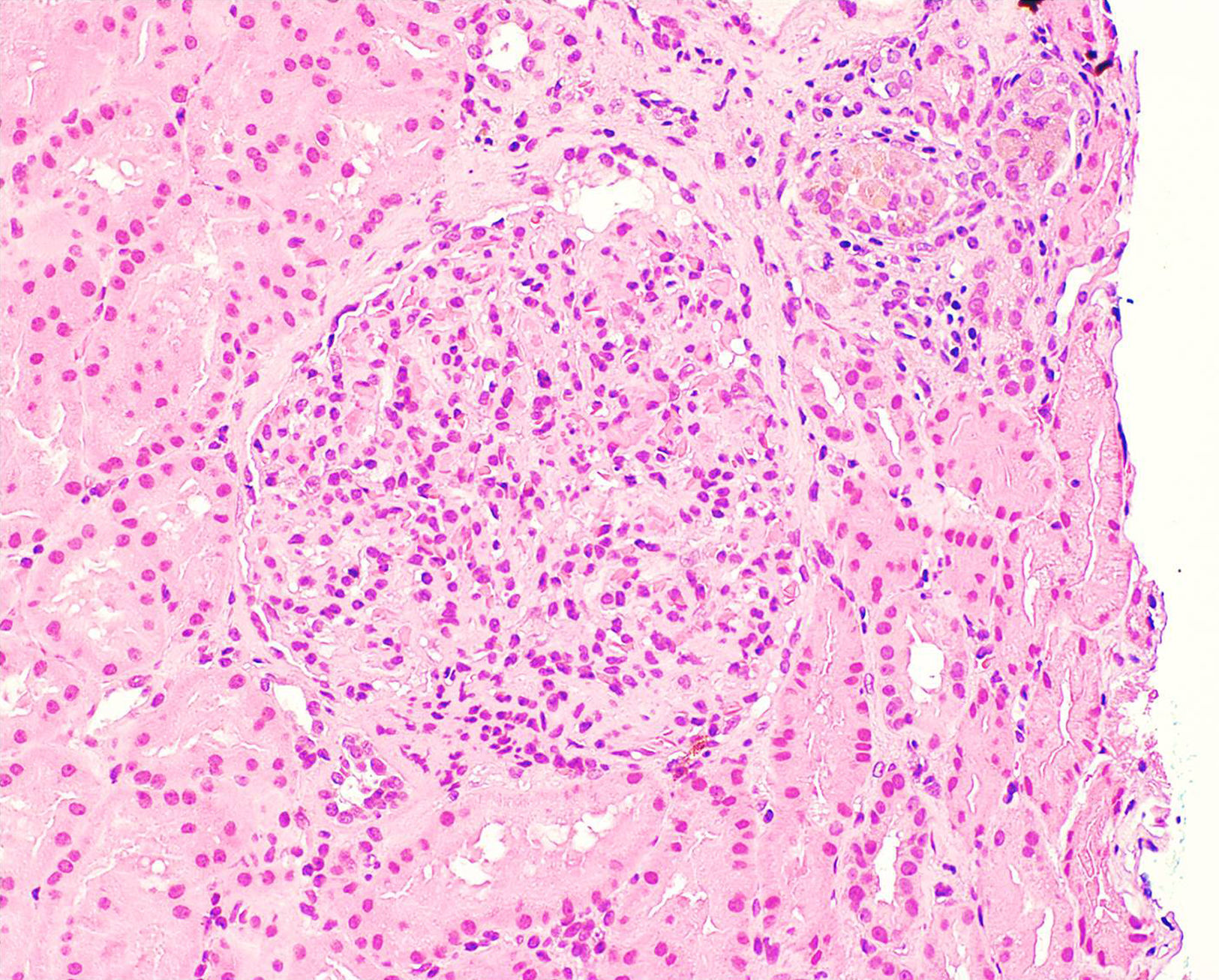

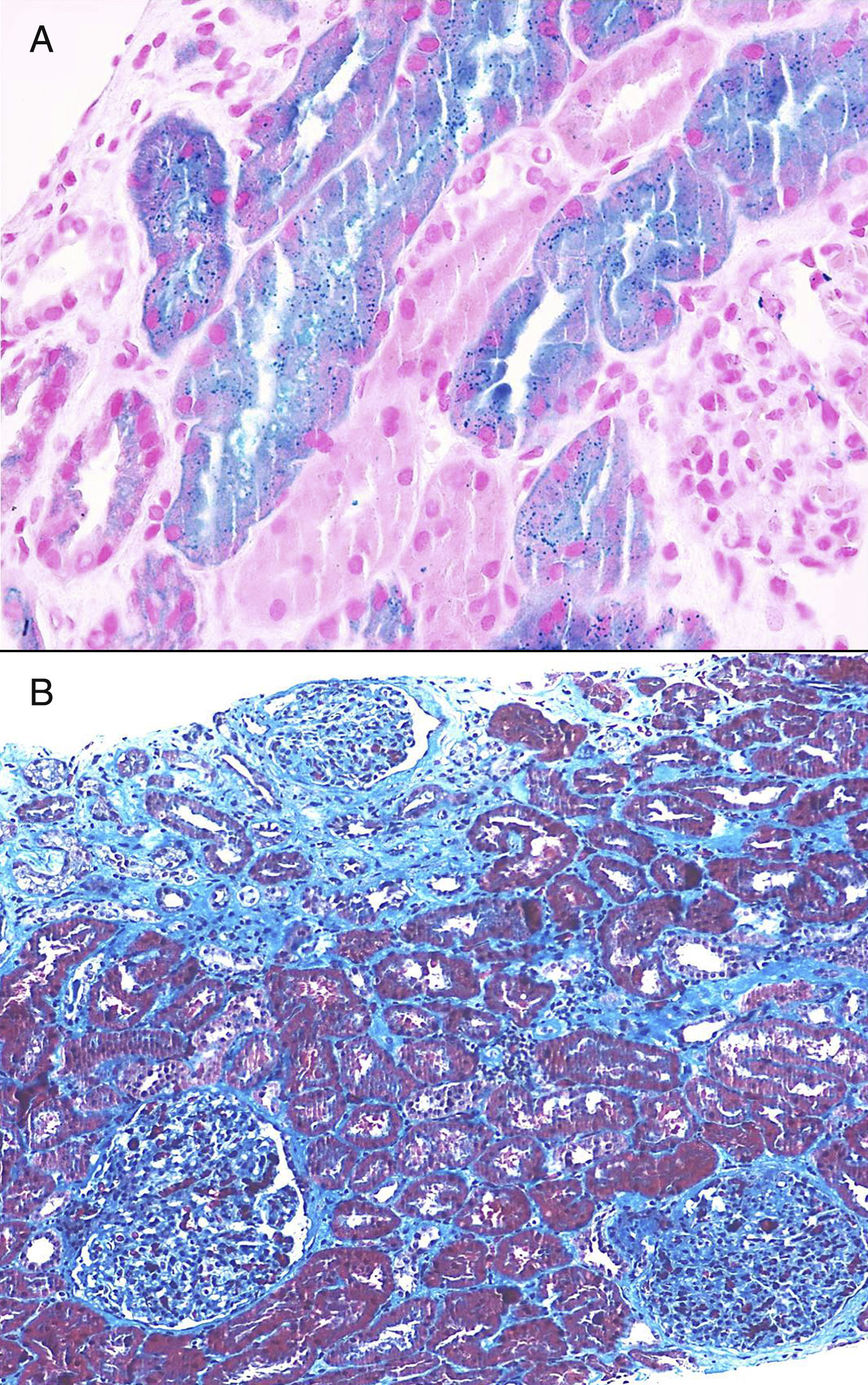

Once proteinuria was confirmed, a renal biopsy was performed that showed glomerular hypertrophy without sclerosis, enlargement of the glomerular capillaries and the presence of sickle cells within the capillaries (Fig. 1). The tubules have cells with haemosiderin by Perls staining and occasional areas of atrophy associated with fibrosis seen with trichrome staining (Fig. 2A and B). Interstitial vessels do not reveal abnormalities and direct immunofluorescence shows absence of deposits.

The patient is diagnosed of sickle cell glomerulopathy. After one year with valsartan, 80mg/day, proteinuria decreased to 1.6g/24h (albuminuria: 1.1g/24h) and the mean blood pressure was 111/63mmHg by ABPM, values did not allow an increase in doses of ARA-II or double blockage of the renin–angiotensin system due to risk of symptomatic hypotension. At present, renal function is maintained normal with Cr: 0.64mg/dl (MDRD>60ml/min, CKD-EPI: 130ml/min), serum phosphorus 5mg/dl (tubular resorption phosphate: 0.9; tubular reabsorption of urate: 0.9) and urinary sediment continues to be normal.

Sickle cell disease is one of the most frequent hereditary hematological diseases, and it is classified as one of the hemoglobinopathies. This disease is caused by a point mutation that changes glutamine by valine in the globin gene on chromosome 11, it generates hemoglobin S (HbS), which polymerizes in long fibers when deoxygenated, this causes a decrease in erythrocyte deformability and produces cell membrane damage.7 It includes the homozygous state (HbSS), which is the most severe form and it is most frequently in African, Mediterranean and Indian populations and the heterozygous forms HbSC and HbS-beta-thalassemia.8

Renal involvement of sickle cell disease has a great variability. Sickle cell nephropathy can range from difficulty of concentrating urine or hyposthenuria (in our case the urine density was 1006), to renal medullary carcinoma as the most extreme expression of severity.9

A supranormal proximal tubular function may be present (the patient has hyperphosphoremia and increased tubular phosphate reabsorption), microhematuria, microalbuminuria, proteinuria of glomerular origin (detected by Dipstick or more reliably by 24h urine albuminuria), hypertension, acute renal failure and chronic renal failure.8 Renal failure and glomerular proteinuria are risk factors associated with an increase in mortality in patients with sickle cell disease.4,10 It is estimated an overall mortality of 16–18% attributed to renal disease.

In addition to the more frequent form of glomerulopathy (FSG), it may be manifested as membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, thrombotic microangiopathy and sickle cell-specific glomerulopathy.2,8 Biopsy is rarely used to establish the diagnosis; in early sickle cell nephropathy, glomerular hypertrophy is observed and is part of sickle cell disease description in 1960; the most frequent location of glomerular hypertrophy is at the juxtaglomerular level, in addition there is tubular hemosiderin deposits that play a relevant role in the progression of the nephropathy. Other microscopy findings include red blood cell sickling in vasa recta, capillary congestion, mesangial expansion and endothelial lesion expressed as expansion of the lamina rara interna. Renal biopsy is necessary in cases of significant proteinuria (>1g/day) or rapid deterioration of renal function that suggests glomerulonephritis.

We conclude that the appearance of proteinuria in a patient with sickle cell disease should guide the existence of a sickle cell glomerulopathy where the glomerular hypertrophy is the consequence of an increased perfusion. Nephrotic range proteinuria is associated with progression of CKD; it is important to know the type of renal involvement given the high prevalence of glomerulopathy in adults with SCD, for which the renal biopsy can help to mark the evolution and prognosis.

Please cite this article as: Hernández-Gallego R, Cerezo I, Barroso S, Azevedo L, López M, Robles NR, et al. Afectación glomerular en paciente con enfermedad falciforme. Nefrología. 2017;37:437–439.