To the Editor,

Two recent events led to our writing this letter.

One. For 2 or 3 years now, our local biochemistry laboratories calculate the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) by means of the MDRD-IDMS formula (formerly MDRD) and the isolated creatinine value, as per National Kidney Foundation recommendations.1

Yet in October 2011, we still observe the following:

- The constant used by some biochemistry laboratories for the MDRD-IDMS formula is 186, when it should be 175 since the calculation for the serum creatinine value is standardised by IDMS.

- Some laboratories deliver MDRD-IDMS results in ml/min instead of ml/min/1.73 m2. Although it is dependent on an individual’s body surface area, this could lead one to assume that the measurement is absolute, which could have consequences when adjusting doses.

Two. While the new formula for measuring glomerular filtration rate (GFR),2 CKD-EPI, seems to improve on the current MDRD-IDMS formula in both accuracy and precision, it is likely to make things even more confusing when it comes to choosing an equation to adjust a drug dose.

Furthermore, an article recently published in this journal comparing the MDRD-IDMS and CKD-EPI formulas in a Spanish population3 contained what appears to be an erratum in Table 1, which describes the formulas used to calculate CKD-EPI: for males with creatinine levels >80 micromoles/litre, it states to divide by 0.7, and we believe that it should be by 0.9.

In light of all of the above, we would like to make the following observation:

From the 1980s until quite recently, GFR was estimated using the formula published by Cockcroft and Gault (CG) in 1976.4 The result of this equation (an estimation of creatinine clearance) was used to evaluate renal function and adjust the doses of any drugs that so required. We would like to stress that the value obtained by this formula is absolute. This means that it accounts for the individual’s size (since it includes weight among its variables) and gives a result in ml/min (if the body surface area differs greatly from the mean, using ideal rather than true weight is recommended.)

In 1999, 23 years after the CG formula was published, Levey published a new formula for estimating GFR: the MDRD.5 Shortly afterwards, in 2002, the KDOQI proposed using this formula for early detection and classification of chronic kidney disease so that patients in earlier stages would have better access to nephrology care.1 The result given by this formula is dependent on body surface area (ml/min/1.73m2), as is also the case with the recently improved MDRD-IMDS and CKD-EPI formulas.6,2 Since the result is dependent on a surface area of 1.73 m2, we only need the variables age, sex, serum creatinine and race. This formula was recommended by such societies as the Spanish Society of Clinical Biochemistry and Molecular Pathology (SEQC) and the Spanish Society of Nephrology (S.E.N).7

Nevertheless, although generalised use of the MDRD method seems appropriate for categorising individuals in different stages of chronic kidney disease, it causes some problems in adjusting drug doses, especially if the value given by the laboratories is interpreted as an absolute value.

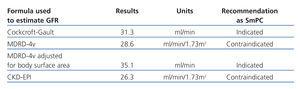

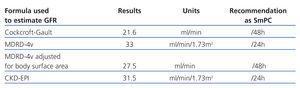

If we consider only the relative results (ml/min/1.73m2) given by MDRD, MDRD-IMDS or CKD-EPI –those results given by biochemical laboratories– individuals with a body surface area >1.73m2 will have a higher absolute eGFR value. This could lead to underdosing the patient. If the patient’s body surface area is less than 1.73m2, the absolute eGFR will be lower, which could lead to overdosing the patient (Tables 1 and 2).

On the other hand, the required dose of a certain drug may vary considerably depending on the equation used to estimate GFR, and this may have clinical repercussions.8 With this in mind, most published drug adjustment guidelines recommend a dose and/or drug interval according to the Cockcroft-Gault formula; very few guidelines make use of MDRD.9 In two recent examples, regulatory authorities based their recommendations on the CG formula:

- The Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products (AEMPS) followed the European Medicines Agency recommendation and modified the SmPC for Pradaxa® (dabigatran) and issued an informative note on 27 October 2011 reminding doctors of the importance of checking renal function before and after treatment with this new drug. They informed that before starting dabigatran treatment, renal function must be assessed in all patients by calculating creatinine clearance (CrCl) in order to exclude patients with severe renal failure (CrCl<30ml/min).10

- The Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s safety update of 1 September 2011 stated that the SmPC had been changed and issued a reminder that “Reclast should not be used (is contraindicated) in patients with creatinine clearance less than 35ml/min”.11

The FDA guidelines for the industry simply cite the CG and MDRD equations as being the most commonly used.

However, experts do not agree on which of the formulas should be used for adjusting doses in patients with renal failure. Some advocate using the equation recommended by the pharmaceutical manufacturer, particularly in the case of elderly patients,12 while others13,14 state that the MDRD and CG equations are completely interchangeable.

In summary, and as a general rule, using the equation recommended by the pharmaceutical manufacturer (mainly CG) seems reasonable. If there is no specific recommendation, the most reliable method of estimating GFR in the target population should be should.

Regardless of which equation is used, we must remember that dose adjustments must be made using absolute GFR values, especially for patients whose body surface area differs greatly from 1.73m2.

Table 1. Recommended dabigatran dose adjustments according to the glomerular filtration rate estimated by different equations

Table 2. Recommended daptomycin dose adjustments according to the glomerular filtration rate estimated by different equations