Introducción y objetivo: El cáncer es una de las principales causas de muerte con injerto funcionante en los pacientes trasplantados renales. La creciente edad de los pacientes remitidos para su inclusión en lista de espera ha elevado el riesgo de neoplasias en esta población. El objetivo de este estudio fue analizar la incidencia de neoplasias en los pacientes evaluados para su inclusión en lista de espera para trasplante y en los trasplantados renales. Métodos: Entre noviembre de 1996 y noviembre de 2007 fueron evaluados 825 pacientes en la consulta de trasplante renal; 467 habían recibido un injerto renal, 120 permanecían en lista de espera y 238 habían sido desestimados o fallecieron estando en lista de espera. Resultados: Se diagnosticaron 97 tumores, 33 de ellos en 32 pacientes candidatos a trasplante y 64 tumores en 62 pacientes trasplantados. El análisis comparativo entre los pacientes candidatos (incluidos o no en lista de espera) y aquellos trasplantados mostró que los primeros presentaron con mayor frecuencia tumores sólidos, mientras que los segundos presentaron mayor porcentaje de neoplasias cutáneas. La incidencia de tumores sólidos en la población trasplantada fue del 5,6%. El tiempo entre la fecha de trasplante y el diagnóstico del tumor fue de 42,6 ± 32,7 meses, siendo el 48% de las neoplasias diagnosticadas en los primeros tres años postrasplante. Al analizar pacientes trasplantados con y sin diagnóstico de neoplasias, observamos que los primeros tenían mayor edad y un mayor seguimiento postrasplante. La supervivencia del injerto fue similar entre ambos grupos, siendo la supervivencia del paciente a los cinco años significativamente menor en el grupo de pacientes trasplantados con tumor. Conclusiones: La notable incidencia de tumores pre y postrasplante enfatiza la necesidad de una búsqueda y un seguimiento exhaustivos de tumores en los pacientes trasplantados y una alta sospecha en la valoración pretrasplante.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is one of the main causes of death in kidney transplant patients with a functioning graft, and it is thought that it could overtake cardiovascular as the main cause of death in the next two decades.1 Although the introduction of new immunosuppressant agents has resulted in a decrease in acute rejection rates there has been an increase in the number of long-term complications, such as neoplasias.2 Furthermore, the mean age of transplant recipients and patients referred for assessment for inclusion in the kidney transplant waiting list has increased by 10 years in just a decade.3

As in the general population, the main risk factors for developing neoplasms in the population with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are advanced age, male sex, and exposure to carcinogenic agents such as tobacco, alcohol and sunlight.4,5 Specific, risk factors in CKD include malnutrition, metabolic changes, prolonged time on dialysis, retention of carcinogenic compounds, the aetiology of kidney failure and its treatment, and uraemic immune deficiency.6 Following a kidney transplant, there is the added risk of the immunosuppressive treatment7,8 and the reactivation of potentially oncogenic viruses, such as Epstein-Barr, herpes virus type 8, human papillomavirus, hepatitis B and C viruses, and a higher risk of developing skin cancer, non-Hodgkin¿s lymphoma and Kaposi¿s sarcoma.9 A study based on the joint registry data from Australia and New Zealand (ANZData) comparing the neoplasia incidence rate in 28,855 patients with CKD who were on dialysis or transplanted showed that the risk of developing 18 different kinds of neoplasms was 3-fold.10

The development of cancer following kidney transplantation could be due to: de novo post-transplant malignancy, transfer of tumours inadvertently from the donor or recurring/preexisting neoplasms in the recipient that may not have been detected during pre-transplant screening.11 The advanced age of potential kidney transplant recipients not only increases the risk of developing de novo post-transplant neoplasms, but also the probability of having occult malignancy prior to transplantation. In this context, the aim of this study was to determine the incidence rate of neoplasias in the population referred to a kidney transplant unit, including those patients awaiting kidney transplantation and those having already undergone a kidney transplant.

DESIGN OF THE STUDY

Retrospective and observational study carried out in the kidney transplant unit in our hospital over an 11-year period (November 1996-November 2007).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The population covered by our transplant unit consists of about a million inhabitants. During the study, approximately 825 patients were evaluated in the kidney transplant unit. On average, 75 patients/year are sent to our unit to be evaluated for transplantation, out of which approximately 60 patients/year are included on the waiting list for kidney transplantation. The remaining patients are deemed unsuitable for transplantation or referred to another centre (kidneypancreas transplant). The general criteria for referring patients who are diagnosed with chronic renal failure and apt for receiving a transplant include: age < 75 years except in certain circumstances, life expectancy > 2 years and absence of serious illnesses (advanced chronic liver disease, chronic respiratory failure, untreatable heart disease or active infectious disease, recent or metastaticneoplasia or severe psychiatric disorders).

CKD patients on dialysis were assessed according to a standard protocol at their respective centres to determine their suitability for kidney transplantation using preliminary imaging and laboratory tests before referral to the kidney transplant division. This protocol included specific examinations designed to rule out the presence of neoplasias, as well as interval at which the tests need to be repeated (table 1).

We do not know the number of patients turned down for transplantation due to a tumour being detected by the referring haemodialysis unit, nor do we have information on the tumour types. However, we do have data on those patients in whom the neoplasia was diagnosed when they were already on the transplant waiting list.

At the end of the study, 467 patients had received a kidney transplant, 120 were still on the transplant waiting list and 238 patients had been excluded or had died while waiting for a transplant. 102 patients lost the graft, and 30 received a second transplant.

We collected data from all potential kidney transplant recipients (whether or not they were on the waiting list) and those already transplanted who had been diagnosed with a tumour and compared them with the patients who had not developed a neoplasm. The following variables were analysed: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), CKD aetiology, time on dialysis, personal history of cancer, immunotherapy treatment, tumour type, time between the transplant date and diagnosis of the tumour, smoking history and viral serology.

STATISTICS

Values are expressed as percentage, mean and standard deviation, range and 95% confidence interval. The Chisquare test or Fisher¿s exact test were used as appropriate for comparing categorical variables. The differences between the means were analysed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Values of p < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The survivalanalysis was carried out by the Kaplan-Meier method and the Log-rank test. Data was analysed using SPSS statistical software, version 15.

RESULTS

In a period of 11 years, 97 tumours were diagnosed in 825 patients followed up in the kidney transplant division. A total of 33 tumours were diagnosed in 32 potential transplant recipients: 17 tumours were detected during the evaluation process, and the affected patients were not included on the transplant waiting list (6 prostate, 2 bladder, 3 kidney, 2 larynx and 2 colon tumours, as well as 1 multiple myeloma and 1 basal cell carcinoma excluded due to cardiovascular risk); the other 16 tumours did not contraindicate transplantation. Of this last group, 8 received a transplant (5 had basal cell carcinomas, 2 squamous cell carcinomas and 1 rectal neoplasia after a five-year follow up period).

The 467 transplanted patients were followed up for a mean of 79± 34 months (range 8-132) from the transplant date; 62 patients were diagnosed with 64 de novo tumours, representing a neoplasia incidence of 13.2%.

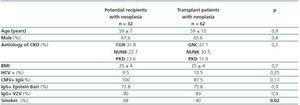

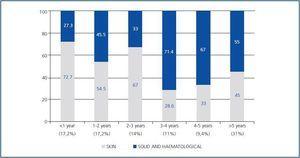

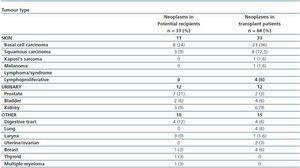

The characteristics of the potential transplant recipients and the transplant patients diagnosed with neoplasias are similar. The two groups mean age was 59 years and they were, predominantly male. There were no differences in CKD aetiology, BMI, viral serology (VHC, CMV, Epstein-Barr or varicella zoster). There was a larger number of smokers in the group of potential kidney transplant recipients that had a diagnosis of neoplasias (68 vs. 40%, p = 0.02) (table 2). For this group, the mean time between starting renal replacement therapy and the diagnosis of neoplasia was 30.8 ± 44 months. For the transplant group, the mean time between the transplant date and the diagnosis of the tumour was 42.6± 32.7 months (95% CI 34-51 months, range 2¿124). In these patients, 48% of the neoplasias were diagnosed in the first three years after transplantation, particularly skin neoplasms (figure 1). In the potential transplant recipient group, solid tumours were diagnosed more frequently than in the transplant group (70.6 vs. 47.6%, p = 0,03), while in the transplant group, cutaneous neoplasias were more common (52.4 vs. 29.4%, p = 0.03). Solid neoplasias in possible transplant candidate patients were predominantly located in the following areas: genitourinary (7 prostate, 3 kidney, 2 bladder), gastrointestinal tract (2 colon, 1 rectal, 1 stomach) and larynx (3 cases). Among transplant patients, the most common solid neoplasia was renal cell carcinoma (6 cases) (table 3). The incidenceof solid tumours in the transplant population was 5.6%.

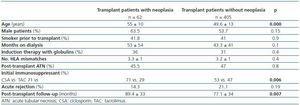

Comparative analysis of the transplant population between those who developed tumours and those who did not showed that the former were older (55 ± 10 vs. 49.6 ± 13 years, p = 0.000) and were more likely to have received ciclosporin rather than tacrolimus as initial immunosupressor treatment (CSA 71 vs. 53%, p=0.006). Patients diagnosed with neoplasias had a longer post-transplant follow-up (89.4 ± 33 vs. 77.1 ± 34 months, p = 0.007). We found no significant differences when comparing by gender, smoking history prior to transplantation, time on dialysis, anti-lymphocyte induction, presence of acute tubular necrosis post-transplant and the number of episodes of acute rejection that were treated (table 4).

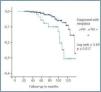

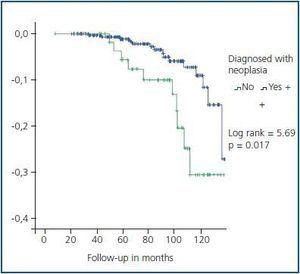

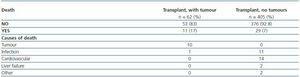

Five year graft survival was similar for both groups (93.2% for transplant patients with a tumour vs. 95.2% for patients with no tumours, p = 0.4). However, patient survival at five years was significantly less in the group of transplant patients with tumours (93.2 vs. 98.8%, log-rank = 5.69, p= 0.017) (figure 2). Ten of the eleven transplant patients died because of the tumour (table 5).

DISCUSSION

Neoplasia is prevalent in both the population on dialysis and in kidney transplant recipients.12 In the latter group, neoplasia is one of the main causes of death and could become the leading cause. In the present study, we determined the frequency of neoplasms in our kidney transplant unit, in both the possible candidates for renal transplantation and the kidney transplant recipients.

A significant aspect of our series was the high number of neoplasias diagnosed during the patient¿s evaluation process for inclusion on the waiting list and on patients on the waiting list for a kidney transplant. We feel that this issue has not been stressed enough in the literature and that it may be increasingly relevant due to the increase in age of this population. It is important to note that the population of potential transplant recipients in our study may not be representative of the general population on dialysis, given that in some cases neoplasias were diagnosed in the patient¿s referral centre and these patients were not referred to the transplant unit and no information was given in this regard to the transplant centre. We would like to point out the importance of the work carried out by the urologists who evaluate these patients in their weekly clinics, a fact that may explain the high incidence of prostate tumours diagnosed in possible potential transplant recipients.

For the first three years following the transplant, the high incidence of tumours is similar to that of the patients being evaluated for transplantation suggesting the pre-existance of risk factors that could worsen with the immunosuppressive therapy. Our findings show that apart from the well recognised neoplasms of the transplant population (cutaneous and lymphoproliferative disorders), the most common solid tumours with the worse prognostic impact are similar in both populations, the genitourinary tract. These findings should give an idea of what examinations must be carried out frequently for early diagnosis of neoplasias in these patients. In our experience renal ultrasound and PSA testing proved particularly useful. In contrast, testing for FOB (faecal occult blood) has not been shown to be very sensitive,13 since four patients diagnosed with colon cancer in our study had previously had a negative test result. In this high-risk population, the screening should include periodic rectosigmoidoscopy in patients older than 50, following the criteria recommended by scientific societies.14,15 The use of a barium enema is particularly useful in older patients with a high number of diverticula and a risk of post-transplant perforation.16

Skin tumours were more prevalent among the transplant patient group, and we observed a higher incidence of basal cell carcinoma than squamous cell carcinoma, contrary to what is published in the literature.17 This could be explained by better detection of this type of lesion in dermatology check-ups or due to the patients¿ advanced age or posttransplant follow up period. Initial treatment with ciclosporin was associated with a higher frequency of neoplasias in this group, as has been previously reported.17,18 In our study, we cannot discard the possibility that this was skewed by having a longer post-transplant follow-up for patients on ciclosporin than for those treated with tacrolimus. Also worthy of mention is the low frequency of lymphoproliferative disorders and Kaposi¿s sarcoma observed in the transplant patients, particularly when the former have been related to the use of anti-lymphocyte globulin (31% of our patients received induction therapy with thymoglobulin although doses were low). We could speculate on the protective effect of widely used ganciclovir-valganciclovir prophylaxis for CMV-related disease during the three first months following the transplant, although longer follow-up is needed in order to prove this hypothesis.

The incidence of de novo neoplasms in the transplant group is significantly higher than that in the general population, and the prognosis in the former group is also worse.19 Using US Registry data on 35,765 transplants, Kasiske showed that compared with the general population, neoplasia rates posttransplantation were 2-fold higher for the colon, lung, prostate and breast and 3-fold higher for bladder and testes. Melanoma, leukaemia and cervical neoplasms are 5-fold commoner in transplant recipients. The rates for kidney cancer are 15-fold and for Kaposi¿s sarcoma, non-Hodgkin¿s lymphomas and non-melanoma skin cancers the rates are over 20-fold more common.20 An Italian study of 3,500 transplant patients demonstrated that the 10-year patient survival rate was 92.8% for transplant patients without tumours and 56.6% for those with neoplasia of any type.21 ANZData registry data showed that 67% of deaths in transplant patients with tumours were caused by the neoplasia.11

Our findings suggest that the prevention of neoplasmas posttransplantation should be based on proper examination of the transplant candidate population, including periodic check-ups while patients remain on the waiting list. After a patient receives a kidney transplant, we should reach a delicate balance between the immunosuppresion and the immunological risk, identifying those patients who might benefit from early conversion to proliferation signal inhibitors.

Initial treatment with or conversion to this drug group appears to be followed by lower rates of neoplasia, and it has been shown to be effective for treating patients with certain tumours, particularly skin tumours and Kaposi¿s sarcoma.22

Table 1. Tests for neoplasia detection

Table 2. Epidemiological characteristics of kidney transplant patients and potential transplant recipients diagnosed with neoplasia

Figure 1.

Table 3. Tumour type by group

Table 4. Epidemiological characteristics of transplant patients with positive or negative diagnosis of neoplasia

Figure 2.

Table 5. Causes of death in transplant patients