To the Editor,

We present a new case that illustrates the difficulty in differentiating between a growth hormone (GH) secretion disorder and acromegaly in a patient with chronic kidney disease (CKD) due to changes in growth hormone levels caused by uraemia.

CASE REPORT

A 48-year old patient was referred to hospital after the outpatient clinic detected a serum creatinine of 7.56mg/dL.

Significant exam findings included blood pressure: 163/111mmHg, Weight: 105kg, Height: 190cm, Body mass index: 29kg/m2. Slight cognitive deficit. Corpulent body phenotype. Facies with prognathism and macroglossia, thick lips, prominent brow ridges (Figure 1), deep voice. Normal on auscultation. Normal fundoscopy. The patient reported no changes in body morphology.

Ultrasound imaging showed kidneys of a size at the lower limit of normal, with markedly thinned bilateral renal parenchyma, almost non-existent.

Laboratory tests on admission showed characteristic uraemia biochemical parameters with negative viral serology and normal immunologic tests. Hormone determinations were also performed:

- Cortisol: 23mcg/dL (6-28) TSH: 1.01mcIU/mL (0.27 to 4.2).

- Renin: 29.7micro IU/mL (2.8 to 39.9).

- Aldosterone: 4.24ng/mL (10-160).

- FSH: 12.4mIU/ml (1.5 to 12.4) LH: 8.4mIU/mL (1.7 to 8.6).

- Prolactin: 553mIU/L (86-324), total testosterone: 1.99ng/mL (2.5-8.4).

- GH: 4.24ng/mL (0-1).

- Somatomedin C (IGF1): 670ng/mL (100-358).

- IGF1-BP3: 7.59micro/mL (3.3 to 6.7).

- ACTH: 39pg/mL (8-46).

Hypertension was controlled with medical treatment. Due to renal function deterioration of unknown etiology, treatment was begun with chronic HD.

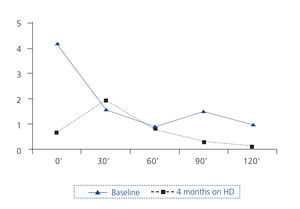

An oral glucose overload test (OGOT) was performed (Figure 2).

At this point, we suspected acromegaly, based on phenotype and hormone profile (increase in GH, IGF-1 and IGF1-BP3; OGOT with no clear suppression of GH). It was not possible to perform magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pituitary due to patient and family refusal.

Four months later, an MRI was finally performed without paramagnetic contrast. The size of the pituitary was within normal limits, and the pituitary stalk was centred. A new OGOT was performed, showing normal baseline GH with paradoxical increase at 30 minutes, but with adequate suppression within two hours (Figure 2).

At that time, the levels of IGF-1 (340ng/mL) and IGF1-BP3 (6.3mcg/mL) were also normal. Prolactin continued to be high and testosterone was normal. Currently, the patient undergoes regular endocrinology check-ups and continues on haemodialysis.

DISCUSSION

Appearances can be deceiving when it comes to diagnosing acromegaly in uraemic patients. Our patient did not suffer from acromegaly, in spite of the fact that his morphological features and first hormone determinations were compatible with this condition.

After reviewing the literature, we found two similar cases1,2. In the case of our patient, we were uncertain until we had the MRI results.

Repeated functional tests after several months on haemodialysis showed normal values.

Hyperprolactinemia, also seen in our patient, is a common finding in CKD in both sexes3.

Acromegaly is a rare condition in Spain, with an estimated incidence of 3-4 cases per million inhabitants a year and a prevalence of 36 cases per million4. OGOT is the test that confirms diagnosis. In healthy individuals, it leads to suppression, within two hours, of serum GH values below 1ng/mL. Furthermore, it has been reported that several disorders, including renal failure, can lead to OGOT false positives.

There are not many studies that have assessed renal function in acromegaly. In a recent study, a large series of patients was analysed, concluding that acromegaly is characterised by significant changes in renal structure and function6. It may be assumed that perhaps through a hyperfiltration mechanism, renal function could eventually deteriorate in these individuals.

Often studies of GH secretion in CKD have been inconclusive or have produced conflicting results, possibly due to the pulsatile nature of GH, increased retention and catabolism in uraemia, variable activity of transporter proteins and the effects of stress, malnutrition and other unknown factors7. There is evidence that uraemia causes a state of resistance to growth hormone3,8,9 and this would explain why acromegaly is so rare in renal patients. Some studies have shown that dialysis can significantly reduce GH levels to normal levels9,10, as occurred in our patient.

In conclusion, our case illustrates the difficulty of interpreting GH/IGF-1 axis results in uraemia. We should remind doctors of these alterations when assessing probable acromegaly in a patient with CKD. A complete hormone study, including imaging, and monitoring of hormone levels after starting dialysis, will help establish the correct diagnosis.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Figure 1. Patient whose phenotype on admission led to suspicion of acromegaly

Figure 2. Changes in levels of growth hormone in ng/ml of patient at rest with an oral glucose load of 75g