Anaemia in kidney transplant recipients has received limited attention in the literature despite its high reported prevalence of 30%–40%. It is a multifactorial disease that may be associated with: blood loss; iron and/or folate deficiency; chronic inflammatory processes; other factors related to kidney transplantation such as immunosuppressive drugs (antimetabolites, antithymocyte globulin); post-transplantation prophylaxis (valganciclovir, trimethoprim); infections associated with immunosuppression such as parvovirus B19 (PV-B19), Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus; and, finally, chronic graft dysfunction and graft rejection.

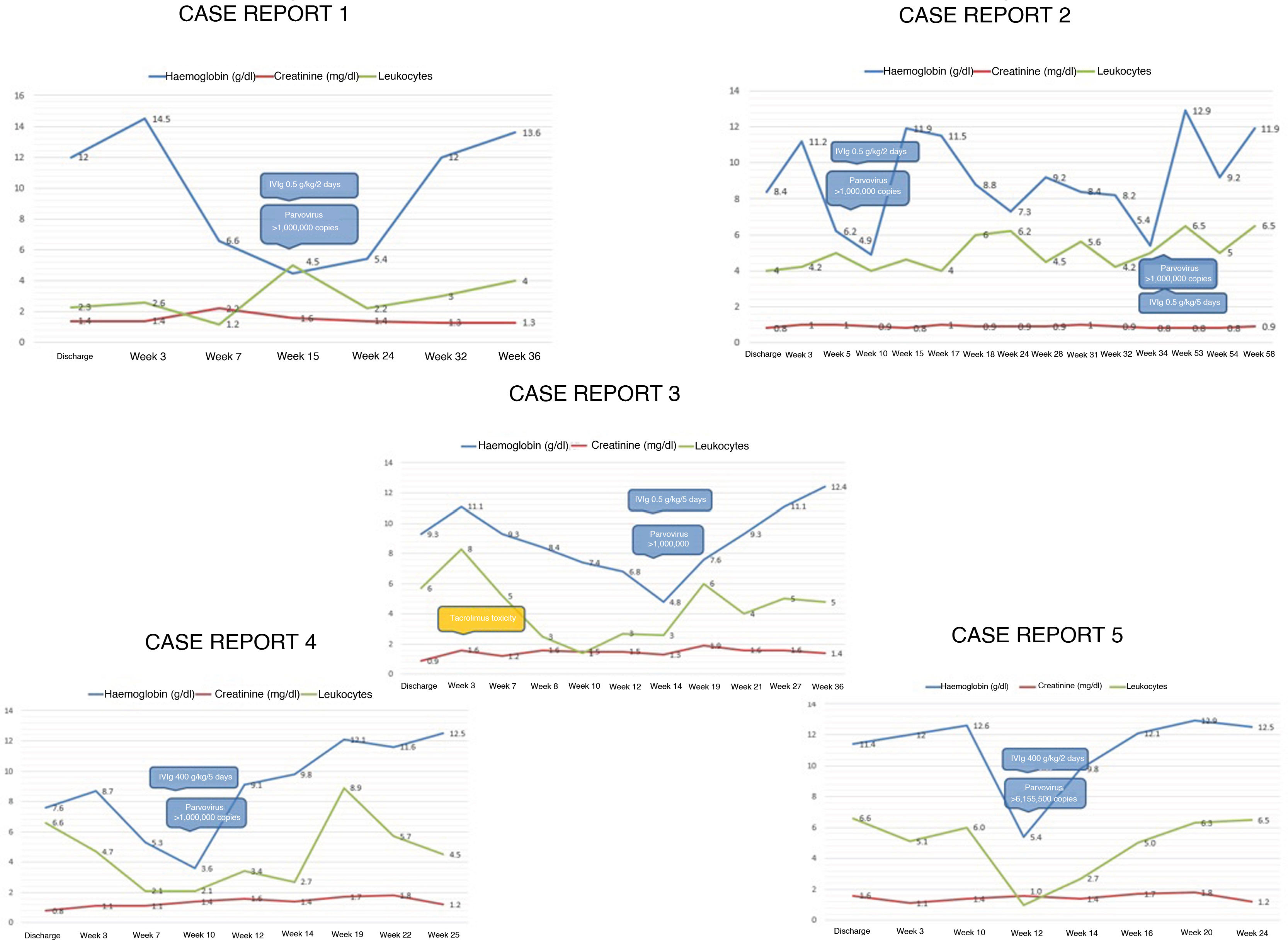

We report five cases of anaemia in live-donor kidney transplant recipients, detected in the first year of follow-up, associated with PV-B19 infection. The average age of manifestation was 27 years, the majority were women and the most commonly used induction therapy was Thymoglobulin (n = 4; 80%). The method of diagnosis used in all cases was PCR, the average haemoglobin level at the time of diagnosis was 4.9 g/dl, the average time of manifestation was nine weeks after transplantation and the primary symptom was anaemic heart disease. In just 60% of cases, patients developed modest decline in kidney function; however, in two cases toxic levels of calcineurin inhibitor were detected and in one case a urinary tract infection was identified, with creatinine returning to its baseline level once all factors were controlled. One relapse was observed, six months later, associated with incomplete administration of immunoglobulin therapy due to the patient's poor tolerance to the therapy. In 80% of cases, immunosuppression was switched from tacrolimus to ciclosporin (Fig. 1).

In the follow-up of transplant recipients with stable kidney function and sudden onset of anaemia, the following workup protocol is suggested: determination of iron kinetics, reticulocyte count, faecal occult blood, bone marrow aspiration in some cases and PCR for PV-B19. The anaemia is aplastic, normocytic, normochromic, severe, non-regenerative (reticulocytopenia) and does not respond to transfusions.

The immune response to PV-B19 infection is influenced by immunosuppressive therapies. Induction therapy with polyclonal antibodies carries a higher risk of developing viral infections within the immediate post-transplantation period, although this is not as a rule. In two cases of this serie, an increase in creatinine was observed, associated with elevated levels of calcineurin inhibitor, the interpretation is that to excessive immunosuppression is as a possible risk factor. Better management of infection is feasible by adjusting immunosuppressive therapy with a switch from tacrolimus to ciclosporin, in pursuit of lower immunosuppressive potency; withdrawing or decreasing the antiproliferative agent (mycophenolate, azathioprine) is another treatment option.1,2

The use of erythropoietin (EPO) is recommended initially; however, it can cause viral resistance to the immunoglobulin. It has been suggested that treatment with EPO facilitates viral infection by stimulating replication of erythroid progenitor cells in bone marrow, which constitute the only cell lines for viral reactivation and replication.3

Regarding diagnosis, IgM determination in symptomatic patients is not the test of choice given the risk of false negatives due to binding of antibodies to viral particles. For this reason, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is preferable. In addition to making the diagnosis, haemodynamic stability must be maintained by means of transfusion of irradiated packed red blood cells with a third-generation filter, and sampling for PV-B19 must be performed, regardless of transfusions, since they do not alter the result.4,5

Molecular biology has detected viral DNA in blood in 20%–30% of transplant recipients. If this is accompanied by mild anaemia, it is not an indication for immunoglobulin treatment since anaemia can remit when other risk factors for developing anaemia are controlled.2

It is required the association of cut-off points between a particular number of copies and a decrease in haemoglobin. It remains unknown whether persistent viraemia is associated with clinical recurrence, patient survival or long-term morbidity.6

The suggested dose of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) is 0.4−0.5 g/kg/day for at least five days, with a cumulative dose of 2−5 g/kg. In >90% of cases, remission of anaemia is achieved with a single cycle; lower doses are associated with a high rate of relapse.7

The detection and management strategies mentioned in this document have yielded good outcomes with haematologic recovery and suitable kidney function after two years of follow-up in our patients. In summary, immunoglobulin administration, switching from tacrolimus to ciclosporin and decreasing the dose or discontinuation of mycophenolate are the treatments reported tha have shown evidence of being effective; however, decisions must be tailored according to the experience of each centre and the clinical course of each case.4,7,8

Please cite this article as: Noriega-Salas L, Cruz-Santiago J, Lòpez-Lòpez B, del Rosario Garcia-Ramirez C, Robledo-Melendez A. Anemia aplásica asociada a parvovirus B19 en trasplante renal de donante vivo: experiencia de un centro de referencia. Nefrologia. 2021;41:599–601.