The current classification of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) is based on immunofluorescence findings, with aetiological and therapeutic implications.1

Idiopathic MPGN is uncommon.2 Treatment recommendations are therefore based on case series and non-randomised clinical trials. Current therapy consists of corticosteroids and antiproliferative agents (mycophenolate, cyclophosphamide), monoclonal antibodies (rituximab, bortezomib) or plasmapheresis.3–5

Worse kidney graft survival and a higher risk of relapse in kidney transplantation have been demonstrated in patients with MPGN compared to other forms of glomerulonephritis.2

We report the case of a 66-year-old man with a history of arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus who, in 2012, developed kidney failure (creatinine 1.5mg/dl, glomerular filtration rate [GFR] 50ml/min) associated with nephrotic syndrome (proteinuria >15g/24h, hypoalbuminaemia and dyslipidaemia), with microscopic haematuria, without casts. The initial workup included antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs), antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), rheumatoid factor, protein electrophoresis in serum and urine (negative, normal C3 and C4).

The results of a kidney biopsy were consistent with type 1 MPGN. Immunofluorescence showed deposits of immunoglobulin G (IgG) (3+), C3 (3+) and immunoglobulin M (IgM) (+) in the mesangium and capillary walls. Neoplasms and infections were ruled out as causes of glomerular injury (Fig. 1).

Treatment was started with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors plus mycophenolate and steroids, with no response after three months. Given the patient's progressive decline in kidney function, a decision was made to switch to oral cyclophosphamide plus steroids. This treatment was suspended after four months due to lack of response. In 2014, the patient started peritoneal dialysis.

In 2016, he received his first kidney graft from a cadaver donor, with five human leukocyte antigen (HLA) incompatibilities. Induction therapy was administered with thymoglobulin (6mg/kg), mycophenolate, prednisone and tacrolimus. In the post-transplantation period, he showed slow recovery of kidney function with creatinine levels of up to 1mg/dl (GFR>70ml/min) and proteinuria levels around 1.5g/24h, on treatment with ACE inhibitors. Three months after transplantation, he presented cytomegalovirus infection, which was treated with valganciclovir with a good response.

Six months after transplantation, the patient presented nephrotic syndrome of new onset, with proteinuria levels of 12 g/day and hypoalbuminaemia, with stable kidney function. An immunology workup and HLA antibodies were negative. The results of a kidney graft biopsy were consistent with immune complex-mediated diffuse endocapillary proliferative glomerulonephritis and C3 deposits. Immunofluorescence showed IgG (3+) and C3 (2+) with a diffuse subepithelial and mesangial granular pattern. The C4d antibody was negative.

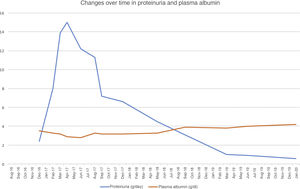

To treat MPGN recurrence, the patient's initial therapy included increasing mycophenolate to a dose of 2g/day and increasing prednisone to a dose of 50mg/day. He presented moderate cytomegalovirus viral load reactivation. Despite treatment, his nephrotic syndrome did not improve, reaching proteinuria levels as high as 17g/24h and serum albumin concentration of 2g/dl. Changes over time in proteinuria and plasma albumin following transplantation are shown in Fig. 1.

Given that the prior cycle of cyclophosphamide had no response, a decision was made to administer treatment with rituximab (375mg/m2). He received a dose of 1g, with no complications. His CD19 lymphocyte levels, monitored every three months, were suppressed during the first year. After starting rituximab, the patient showed gradual resolution of proteinuria as of the first month, and after one year his nephrotic syndrome resolved. As of 2019, he has developed skin spinocellular and squamous cell carcinoma; consequently, he has been switched from mycophenolate to a mammalian target of rapamycin (m-TOR) inhibitor and his tacrolimus dose has been reduced, with no repercussions on his proteinuria. Two years after treatment with rituximab, his proteinuria has continued to drop (<1g/day) and his kidney function is stable.

Post-transplant MPGN recurrence is very common; some series have reported rates as high as 50% in the first 24 months.6 At present, the optimum treatment for recurrence is not clear.

Rituximab (an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) has been used in case series, achieving complete or partial remission, although its dosing remains unclear.7

Other authors have used bortezomib in cases of MPGN with kappa chain deposits, with no prior diagnosis of dysproteinaemia, with a good clinical response.8

In our case, a single dose of 1g was administered with regular monitoring of CD19 lymphocyte levels. As they remained reduced for up to approximately one year, no new doses were proposed. In conclusion, in our case, rituximab was effective in achieving remission of post-transplant recurrent MPGN. Complete response to treatment with rituximab is not immediate, with effects beyond one year following administration. Monitoring of CD19 lymphocyte levels may be useful to minimise the dose taken, and is particularly useful in transplant recipients given the cumulative immunosuppression load with the onset of undesirable effects, such as tumours and infections.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Cruzado Vega L, Santos García A., Dosis única de rituximab como tratamiento de recidiva de glomerulonefritis membranoproliferativa en trasplante renal. Nefrologia. 2021;41:601–603.