Secondary hyperparathyroidism (HPT) is a very common complication that worsens and exacerbates chronic kidney disease (CKD). It is associated with the genesis of vascular calcifications and with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.1,2

According to data from the Spanish Society of Nephrology, more than 23,000 patients in Spain undergo haemodialysis (HD), and approximately 35% of these patients have HPT.3

The treatment of HPT is based on the control of dietary phosphorus intake, the administration of phosphate binders and vitamin D supplements, the activation of vitamin D receptors, and the administration of calcimimetic agents that activate the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) of the parathyroid glands.4,5 Most of these treatments are administered orally and are not entirely free from adverse effects; therapeutic outcomes depend to a large extent on patient adherence. Calcimimetic agents in particular are associated with gastrointestinal side effects.1,4

Recently, a new long-acting calcimimetic agent (etelcalcetide) was approved for intravenous use in HD patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism.5 Etelcalcetide binds directly to CaSR, inhibiting the production and secretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH) by the parathyroid glands. One of the main advantages of the drug is its intravenous route of administration, which is likely to promote patient adherence to treatment.5

Since there are very few reports on its use in Spain, we believe that our experience in a patient with severe HPT and poor adherence to oral calcimimetics will be of interest.

This was a 57-year-old patient with CKD secondary to autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, who had been receiving HD since June 2011. She had undergone surgery for breast cancer in 2013, and presented difficult-to-control HPT despite treatment with lanthanum carbonate (2g/8h), calcium acetate (500mg/day), sevelamer (1600mg/8h), cinacalcet (60mg/day) and IV paricalcitol (1μm after each HD session).

The patient had complained of gastrointestinal symptoms since the start of treatment with cinacalcet, which persisted despite antiemetics. The nausea and vomiting at times even prevented her from eating. Gastroscopy was performed, which was normal.

We requested authorisation to use etelcalcetide for compassionate use. Cinacalcet was discontinued, and after 10 days treatment was started at a dose of 2.5mg after each HD session. Calcifediol was discontinued, but paricalcitol was maintained.

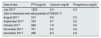

The results are shown in Table 1.

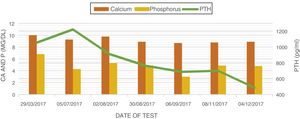

Changes in patient's serum level over time.

| Date of test | PTH (pg/ml) | Calcium (mg/dl) | Phosphorus (mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|

| July 2017 | 1223 | 9.3 | 4.3 |

| Start of treatment with etelcalcetide (07/08/2017) | |||

| August 2017 | 912 | 9.8 | 5.3 |

| September 2017 | 764 | 8.7 | 3.0 |

| October 2017 | 686 | 7.8 | 5.6 |

| November 2017 | 701 | 8.4 | 4.9 |

| December 2017 | 486 | 8.4 | 4.8 |

PTH: parathyroid hormone.

Etelcalcetide reduced intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) levels by 56% after 2 months. Phosphorus and calcium levels were also maintained within reference ranges, with no symptoms of hypocalcaemia. The nausea and vomiting ceased, and the patient was able to increase food intake and progressively gain weight (Fig. 1).

Etelcalcetide was shown to be more effective than placebo in patients on HD, and reduced iPTH levels by 30% or more in 76% of treated patients compared with 10% of patients treated with placebo.6 In a recent clinical trial, 683 patients on HD with secondary HPT and serum iPTH levels of over 500pg/ml received etelcalcetide or cinacalcet for 26 weeks. The results showed that etelcalcetide reduced iPTH levels by more than 30% in 68.2% of patients compared to 57.7% of those treated with cinacalcet, with a similar reduction in serum calcium.6 Furthermore, the incidence of gastrointestinal side effects was lower in patients treated with etelcalcetide.6

In summary, etelcalcetide is a promising drug in the treatment of HPT in HD patients. It has shown at least similar efficacy to cinacalcet, and its main advantages are improved adherence to treatment in polymedicated patients, and a lower rate of gastrointestinal side effects.5,7,8

Please cite this article as: Villabón Ochoa P, Sánchez Heras M, Zapata Balcázar A, Sánchez Escudero P, Rodríguez Palomares JR, de Arriba de la Fuente G. Una luz en el control del hiperparatiroidismo secundario. Etelcalcetide intravenoso en hemodiálisis. Nefrologia. 2018;38:677–678.