El carcinoma tiroideo es una neoplasia que tiene una incidencia más alta en pacientes con enfermedad renal crónica. Durante los últimos años se ha avanzado en las pruebas diagnósticas y terapéuticas. Los pacientes de diálisis son un grupo particular, al ser detectado el cáncer de forma indirecta en el estudio del hiperparatiroidismo secundario y durante el estudio previo al trasplante renal. La tiroidectomía es el tratamiento definitivo, pero en pacientes con riesgo de recidiva es necesaria la terapia ablativa con yodo radioactivo I-131, que es predominantemente excretado por vía renal, por lo que su uso en pacientes en diálisis supone un problema de dosificación. Se presentan dos casos de pacientes en hemodiálisis sometidos a radioablación con yodo radiactivo I-131, que con un manejo multidisplinar produjo los resultados esperados en los pacientes.

Thyroid carcinoma is a neoplasia with a higher incidence in patients with chronic kidney disease. In recent years advances have been made in diagnostic and therapeutic trials. Dialysis patients are a particular group, their cancer being detected indirectly in the study of secondary hyperparathyroidism and during the study prior to renal transplantation. Thyroidectomy is the definitive treatment, but in patients with risk of recurrence, ablative therapy is required using radioactive iodine I-131, which is predominantly eliminated by renal excretion, therefore its use in patients on dialysis poses a problem in terms of dosage. Two cases are presented of patients on haemodialysis undergoing radioablation with radioactive iodine I-131, which with multidisciplinary treatment had the expected results in the patients.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of thyroid cancer has increased more in recent years, at least in the United States,1 although this phenomenon may be due to a mere increase in its detection.2,3 The most common type of thyroid cancer is papillary carcinoma (around 80%).

The current diagnostic study includes serum thyroglobulin levels, cervical ultrasound and recombinant human thyroid stimulating hormone (rhTSH). This approach is less traumatic for the patient than previous approaches, as stated in the 2006 European Guidelines (European Thyroid Association)4 and by the Spanish Society of Endocrinology.5

Patients with chronic renal failure on dialysis are at greater risk of suffering cancer.6,7 Thyroid cancer is often found incidentally while studying secondary hyperparathyroidism or during the study for patient inclusion on the kidney transplant waiting list.

Once the total thyroidectomy has been performed, the treatment of choice is ablation therapy with radioactive iodine I-131, but since iodine is predominantly eliminated via the kidneys (90%),8 its removal is reduced in patients with chronic kidney disease, especially those on dialysis. The resulting high radioactive dose means a high risk of exposure for the patient and dialysis staff, as well as contamination of dialysis machines.

Radiophysics services have facilities and rigorous procedures for monitoring and controlling this risk of exposure to radiation. However, haemodialysis patients require a controlled fluid elimination system and more frequent monitoring of radioactivity due to the lack of normal renal elimination of the radiopharmaceutical.

Below, we describe the management of two haemodialysis patients with thyroid cancer treated with the radiopharmaceutical.

CASE STUDY 1

A 51-year-old male patient with chronic kidney disease secondary to polycystic kidney and liver disease, on haemodialysis since September 2010. After finding a thyroid nodule with suspected malignant cytology in the pre-kidney transplant study, a thyroidectomy was performed.

The pathology report showed papillary thyroid carcinoma, located in the thyroid isthmus, 1.5cm in diameter, with free surgical margins and with extrathyroidal extension to the perithyroidal tissue and absence of lymphovascular or perineural invasion (pT3Nx).

We prepared a special room in the metabolic therapy unit, which is dependent on the nuclear medicine service and is isolated in accordance with current regulations. In order to be able to carry out haemodialysis, portable equipment was installed for treating dialysis water (DWA GmbH & Co. KG HemoRO 3000). We connected the dialysis monitor outlet to the radioactive waste container located in the patient’s bathroom using a hose. The patient was subsequently admitted for ablation therapy with radioactive iodine I-131 in September 2012, in accordance with the following protocol:

- Administration of rhTSH (Sanofi Thyrogen®) on days -2 and -1 (with the objective of achieving a TSH level >30µIU/ml); on day 0, he was administered an oral dose of 100mCi (3700MBq) of radioactive iodine I-131, immediately after an ordinary haemodialysis session in the haemodialysis unit of our hospital. Before pre-ablation, he had TSH of 611µIU/ml and free T4 of 1.83ng/dl.

- After administering the radiopharmaceutical, we performed two daily haemodialysis sessions in the adapted room of the metabolic therapy unit, 20 and 44 hours after administering the radioactive iodine I-131. The sessions lasted 4 hours, using the Integra® (Hospal) dialysis machine with HF80s® (Fresenius) high-flux dialysers, dialysate of Ca 2.5/K 1.5mEq/l and a blood flow of 380ml/min. We obtained ultrafiltration of between 1.5 and 2.3 litres and blood pressure remained stable at 110/80mmHg.

- Every day, we measured the dose of radiation emitted at different points in the patient environment. We used a Rotem Ram Gene 1 area detector. The dose received by the nurse was measured with a personal Atomtex AT2503A direct-reading detector. In any case, we adhered to the radiation protection regulations required by current Spanish legislation, our hospital’s radiation protection manual and nuclear medicine radioactive facility operation regulations, as well as patient management instructions issued by the radiophysics service.9

- The dose rate in the patient environment was considered suitable for patient discharge from the hospital (16.7µSv).9 Radioactivity levels in the nurse at the end of ablation treatment were 21.55µSv.

- The patient was discharged three days after radioactive iodine I-131 administration, after we explained radiation protection measures to him. He had thyroglobulin of 6.98ng/ml, anti-thyroglobulin antibodies <15U/ml and uptake in the thyroid bed.

- We did not observe any adverse effects attributable to rhTSH or to radioactive iodine I-131 and did not record contamination of the haemodialysis equipment’s non-disposable devices.

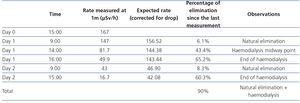

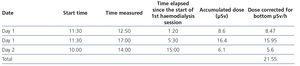

- Patient radioactivity measurements are displayed in Table 1 and those of the nurse in Table 2.

CASE STUDY 2

A 52-year-old female patient, transferred from another hospital, with chronic kidney disease secondary to vesicoureteral reflux, on haemodialysis from 1993 to 1998, received a kidney transplant in 1998, and a parathyroidectomy in 2011. She recommenced haemodialysis in May 2012 and subsequently underwent a left supracondylar amputation due to calciphylaxis.

In September 2011, a thyroid nodule was detected and a total thyroidectomy was performed in May 2012. In the pathology report, she was diagnosed with papillary carcinoma. She was referred to our hospital for ablation treatment with radioactive iodine I-131. Two days before she was admitted, she was administered rhTSH (Thyrogen®).

At the time of admission, the patient was on daily haemodialysis due to poor haemodynamic tolerance.

- On the day of treatment, a haemodialysis session was carried out in our hospital’s haemodialysis unit and the patient was subsequently administered 100mCi (3700MBq) of radioactive iodine I-131 orally. Before ablation, she had TSH of 51.5µIU/ml, free T4 of 0.94ng/dl and free T3 of 1.27pg/ml.

- After the radiopharmaceutical was administered, three daily haemodialysis sessions were carried out, two in the metabolic therapy unit with the Integra® (Hospal) dialysis machine and one in the haemodialysis unit. The sessions lasted 4 hours, and we used Diapes BLS® (Bellco) high-flux dialysers, dialysate with Ca 2.5/K 1.5mEq/l and a blood flow of 300ml/min. Ultrafiltration was between 1 and 1.5 litres per session.

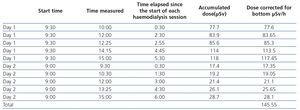

- Each day we measured the rate of the radiation dose emitted (Table 3).

- Three days after administering radioactive iodine I-131, the patient had thyroglobulin of 4.32ng/ml and anti-thyroglobulin antibodies <15U/ml, and uptake in the thyroid bed was adequate.

- The dose rate in the patient environment was considered suitable for patient discharge from the hospital (1.4µSv). She was discharged after we explained the radiation protection measures.

- 48 hours after administration of radioactive iodine I-131, the patient had a fever of 40ºC, secondary to bacteraemia due to methicillin-sensitive staphylococcus aureus. It was interpreted as bacteraemia due to an infection of the haemodialysis catheter with high blood pressure and it responded well to antibiotic treatment. We did not observe any adverse effects attributable to rhTSH or radioactive iodine I-131 and we did not record contamination of the haemodialysis equipment’s non-disposable devices.

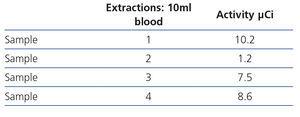

- Tables 4 and 5 display the radioactivity received by the haemodialysis nurse and by blood samples extracted for the diagnosis of bacteraemia.

DISCUSSION

Treating haemodialysis patients with radioactive iodine I-131 is potentially problematic, since its main route of elimination is via the kidneys. In order to carry it out, there was a coordinated study between the nephrology, endocrinology, nuclear medicine and radiophysics services to organise haemodialysis sessions, radioactive iodine I-131 doses and radioactivity measurement.

The first problem that needed to be resolved was the preparation of a room adapted for haemodialysis patients in the metabolic therapy unit. The aim of preparing the room was twofold: on the one hand, collecting the fluid removed in each dialysis session, through an excretion drainage system in the metabolic therapy unit and on the other, installing water treatment portable equipment in the room’s bathroom, in order to mix the water with acid and bicarbonate concentrations.

The fixed dose of 3700MBq (100mCi) for thyroid ablation was approved in Europe in 2005 by the European Medicines Agency prior to preparation with rhTSH.4 In the two cases above, we administered this oral dose of radioactive iodine I-131, which is the same as that used in patients with normal renal function, and before we discharged them from radiation therapy, two daily haemodialysis sessions were required to achieve adequate elimination of the radiopharmaceutical measured by the rate at a distance of one metre.

In the medical literature, there are other reports of radioactive iodine I-131 administration for thyroid cancer treatment in haemodialysis patients. Jiménez et al.10 administered the same dose of the radiopharmaceutical to their three patients as to patients with normal renal function and after five days of haemodialysis, they achieved elimination of over 89% of the initial dose. Hols et al. achieved elimination greater than 90% with three haemodialysis sessions.11

Other authors administered a lower dose than normal12-14 and with variable haemodialysis regimens.

The American Thyroid Association only mentions some lines for patients with renal failure, in which dosimetric measurements must be used for I-131 administration, which is difficult to carry out in clinical practice and does not yield better results than the fixed dose method.15

The European Association of Nuclear Medicine’s Therapy Committee recommends one haemodialysis session after the administration of radioactive iodine I-131, but does not specify a standardised dose of the drug or any method for measuring radioactivity.16

There are few publications on ablation therapy in peritoneal dialysis (PD) and they focus more on dose adjustment than on safety aspects. By way of reference, a patient on continuous ambulatory PD with residual diuresis of 600ml required a I-131 dose of 814MBq (22mCi), with an elimination half-life of 2.9 days and a radioactivity measurement of less than 25µSv/h 24 hours after treatment.17

In the two cases that we reported, there is a major difference in the radioactive dose received by the haemodialysis nurse (21.55µSv/h in case 1 and 145.55µSv/h in case 2), for three reasons. Firstly, in case 1, the process of setting up the monitor and preparing the material was carried out with the patient sitting on a chair behind a lead screen and further away, while in case 2, the patient was in the bed due to her mobility problems. Secondly, in case 1, vascular access was performed with an arteriovenous fistula, while in case 2, a catheter was used, which involves a longer handling period. Thirdly, the second patient’s session was poorly tolerated and required more interventions during the haemodialysis technique than in case 1, due to bacteraemia.

The dose rate at a distance of one metre upon discharge was 16.7µSv/h in case 1 (with two haemodialysis sessions) and 1.4µSv/h in case 2 (with three sessions). These figures are similar to those found by other authors, such as Murcutt et al.18, who also carried out haemodialysis sessions, with less than 20µSv, and Andrés et al.14, with 18µSv after two sessions. Only Gutiérrez et al.19 obtained figures of 1.4µSv on discharge, after two sessions, as with case 2 described, although the latter required three sessions.

In neither of the two cases did the use of rhTSH cause symptoms related to hypothyroidism in patients when levothyroxine was not discontinued.

We should mention that the radioactive monitoring protocol is our own, developed by our hospital’s radiophysics service and based on the Radiation Protection in Healthcare Forum document,9 and it follows the directives of international bodies.

According to this protocol, the radiation limit for non-professionally exposed staff and for the general public is 1mSv/year. The limit for professionals exposed to radiation is 20mSv/year (staff of the metabolic treatment unit).

From our experience, we suggest that when using I-131 in haemodialysis, the involvement of all services is necessary in order to apply small, affordable changes to the metabolic therapy room, such as the portable water treatment equipment (as used for patients in the intensive care unit) and the adaptation of the drainage system. Furthermore, the work of the dialysis nursing staff is very important, and as such, if several treatments are carried out, it would be recommended to rotate staff in order to avoid an accumulation of radiation in one nurse. We propose using a fixed dose of 3700MBq (100mCi) for haemodialysis patients, without forgetting that monitoring during all dialysis sessions is the basis for achieving both effective treatment and safety for patients and healthcare staff. The involvement of the radiophysics service is key in these safety aspects. These recommendations cannot be extended to PD patients who require treatment with I-131, and studies specifically for these patients should be carried out.17

In conclusion, a multidisciplinary approach allows safe and effective therapeutic management of haemodialysis patients. The radioactive iodine I-131 dose applied is that recommended for patients with normal renal function, with the requirement of two subsequent daily haemodialysis sessions to achieve adequate radioactive conditions for discharge from hospital. The nurse received a dose of radiation that did not surpass the safety limits.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Table 1. Patient radioactivity measurements.

Table 2. Nurse radioactivity measurements.

Table 3. Patient radioactivity measurements.

Table 4. Nurse radioactivity measurements.

Table 5. Blood sample radioactivity measurements.