Tuberculosis remains a global public health problem, especially in developing countries. Somewhat more than half of cases (55%) occur in Asia, followed by Africa (31%), with a lower prevalence in the Mediterranean area (6%), Europe (5%) and Latin America (3%).1 Regarding forms of presentation, pulmonary tuberculosis remains the most common. Among extrapulmonary forms, urogenital tuberculosis is the second most common form caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, occurring in around 15–25% of cases.2

In addition to traditional risk factors (underdeveloped countries, immunosuppression due to HIV3), in the 21st century, drug-induced immunosuppression has gained importance in developed countries, especially in patients with solid organ transplants or on biologic treatments for rheumatic diseases.1,4

At our centre, two patients with rheumatic diseases being treated with anti-TNF-α drugs were diagnosed with interstitial nephritis secondary to tuberculosis infection; both followed a good clinical course in terms of kidney function after antituberculosis and steroid treatment. Table 1 provides a summary of the patients' clinical characteristics and clinical course.

The patients' clinical characteristics and clinical course.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | Male |

| Age (years) | 76 | 32 |

| Rheumatic disease | Rheumatoid arthritis | Ankylosing spondylitis |

| Anti-TNF-α drug | Adalimumab | Certolizumab |

| Treatment following TIN diagnosis | Rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol + prednisone | |

| Prior SCr (mg/dl) | 0.86 | 0.67 |

| SCr at diagnosis (mg/dl) | 3.3 | 2.16 |

| SCr after 12 months (mg/dl) | 1.8 | 1.5 |

Anti-TNF-α agents alter the physiological function of TNF-α. This brings about a disruption in cell activation and proliferation, production of cytokines and formation of granulomas, which is key against intracellular infections. This may lead to exacerbation of chronic infections or the onset of new conditions, often of tuberculous aetiology.4

Classic kidney involvement consisted of invasion of the renal medulla by M. tuberculosis, leading to a destruction of the parenchyma and spread towards the urinary tract with resulting ureteral dilatation, with some cases requiring shunting of the excretory tract or even nephrectomy.1 At present, these advanced forms seem to be less common, such that in clinical practice only patients with subacute deterioration of kidney function and a pattern of tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN) — i.e. preserved diuresis with mild or no proteinuria without microhaematuria — are seen. Glomerular involvement and amyloidosis are less common.1

Diagnosis requires a high degree of suspicion, especially if there is only kidney involvement (with no fever or lung involvement). As mentioned above, the most common abnormality is a pattern of TIN with kidney function deterioration associated with sterile pyuria.5 Some cases may show eosinophilia, although this is not a constant.6 Concerning microbiology tests, both urine culture and Ziehl–Neelsen staining in urine usually have low sensitivity.2,5 Compared to the previous microbiology tests, PCR for M. tuberculosis in urine has greater sensitivity and is preferred, as it yields results more quickly. In addition, although the Mantoux test continues to be used, the interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) has a specificity close to 92%.4 Regarding imaging tests, it is recommended that a plain chest X-ray be ordered in all cases to rule out lung involvement; CT and PET/CT scanning are useful in diagnosing spreading of tuberculosis.2,5

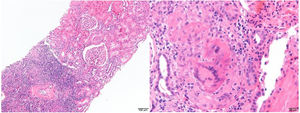

In cases in which a kidney biopsy is performed, histology usually reveals tubulointerstitial involvement with significant inflammatory infiltrate and a predominance of eosinophils. Granulomas do not always develop (they develop in 20–30% of cases, depending on the series) and identification of acid–alcohol-fast bacilli may be difficult.5–7 Immunofluorescence is typically negative, and electron microscopy does not usually show abnormalities.6 Furthermore, in granulomatous interstitial nephritis a differential diagnosis should be made with other possible aetiologies: drugs, systemic diseases (sarcoidosis, Sjögren's syndrome, etc.), bacterial infections, viral infections and parasitic infestations.3,6,8Fig. 1 shows two histological slices from the kidney biopsy in one of our patients.

The treatment regimen is based on four antituberculosis drugs, generally isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol. In addition, it must be kept in mind that concomitant treatment with oral steroids improves the prognosis of the kidneys, since it reduces tubulointerstitial inflammation and carries a lower risk of progression to fibrosis.5,7,8

The prognosis for the kidneys is usually poor in cases with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of less than 15 ml/min at diagnosis, with up to 66% of patients requiring renal replacement therapy after 12 months. However, in subjects with a GFR of more than 15 ml/min at diagnosis, kidney function usually remains stable or improves after treatment.5,6 It is important to start treatment quickly as this favors kidney survival with no need for replacement therapy, as occurred with our two patients. Nevertheless, we stress that although both patients followed a satisfactory course, neither ended up recovering their prior kidney function. This alludes on the one hand to the need for early diagnosis or suspicion and on the other hand to the severity and degree of irreversibility of many of the lesions that develop.

Please cite this article as: Fernández-Vidal M, Canllavi Fiel E, Bada Bosch T, Trujillo Cuéllar H, García Martín F, Gutiérrez Martínez E, et al. Nefritis intersticial tuberculosa, un diagnóstico difícil que precisa de una alta sospecha. Nefrologia. 2020;40:475–477.