This year marks the 35th anniversary of the first pancreas transplant performed in Spain under the leadership of professors Laureano Fernández Cruz and Salvador Gil Vernet at Hospital Clinic in Barcelona.1 Since then, more than 1700 procedures have been performed in Spain, mainly simultaneous pancreas-kidney (SPK) transplants.

Pancreas transplantation has taken a long time to reach maturity as compared to the transplant of other solid organs, but the huge advances in recent years in both the surgical technique and the management of these patients have lead to excellent outcomes. Nowadays, five year patient survival is over 90%, the decrease in surgical complications is reflected by only 6% pancreas graft losses in the first 90 days after transplantation,2 and pancreas graft survival is above 85% at one year and 74% at five years, respectively.3 It has to be said, however, that there is still no standard method for assessing graft function and so the different series have tended to use different methods.

Moreover, long-term results show that the SPK transplant is superior to an isolated kidney transplant, especially when compared with patients under 50 and in kidney transplants with cadaveric donors.4 The uncertainty arises when comparing the SPK transplant with the isolated kidney transplant from a living donor in patients with type 1 diabetes and end-stage renal failure; in this case not only are there improvements in relation to quality of life,5 but also in patient survival after 20 years6 and in the control of cardiovascular disease.7

These data support our criterion that every patient with type 1 diabetes mellitus and end-stage renal failure, on dialysis or pre-dialysis, who meets the appropriate requirements, should be a candidate for SPK transplantation. In parallel, the latest available data from the American registry show an increase in pancreas transplants of the SPK type, with figures at their highest since 2013.8

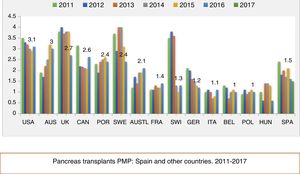

In light of this evidence, the pancreas transplant situation in Spain is paradoxical, with a declining activity. We could argue that it is declining worldwide, but in our case the rate of transplants per million population (PMP) is significantly lower than in a number of different countries in Europe, and in Australia, Canada and the USA, despite being Spain's world leadership in donation and in the transplantation of other solid organs (Fig. 1).

One reason for this situation could be the under-use of the available pancreas grafts; 40% of the pancreases offered for transplantation are not accepted and 50% of those removed are rejected, mainly due to the macroscopic appearance of the organ.

We also have practically no experience in the use of pancreases from donors in asystole; despite this being common in USA and United Kingdom, in Spain, it is still only in the very beginnings, even though these donors currently constitute 26% of the total.

Lastly, another variable that may have an impact on pancreas transplantation activity could be the very strict donation criteria.

This situation has been debated, both within the Grupo Español de Trasplante de Páncreas (GETP) [Spanish Pancreas Transplant Group] and jointly with the Organización Nacional de Trasplantes (ONT) [Spanish National Transplant Organisation], culminating in the ONT publishing a consensus document on criteria for the pancreas donor and the recipient in June 2018.9

To the above reasons we could add as a hypothesis the small number of patients on the waiting lists, secondarily causing better selection of donors by the different transplant groups, looking for the best organ for their few recipients.

It is obvious that waiting lists, whether long or short, are a direct consequence of the indications that we set as healthcare professionals. I think it is worth to think about the indication of transplant data by each autonomous region (Fig. 2).

In 2017, the autonomous region of Extremadura reached the highest rate of indications with 3.7 PMP, followed by Cantabria, Castilla-La Mancha and Castilla-León. In contrast, there were regions that did not indicate any cases. It is true that during the last four years it is observed a great variability, with regions changing from a of zero to more than 3 PMP indications depending on the year.

However, there is not only variability in the indications according to the year analysed, but also between the different regions. According to ONT data, during the last four years Andalusia, Castile-La Mancha, Castile-León and Extremadura are the only regions with a mean number of indications PMP above 2.5.

Other regions such as La Rioja, Madrid, the Basque Country, Cantabria and Asturias remain below the mean of 1.5 indications PMP.

From these data it could assumed that there are fewer patients with type 1 diabetes in end-stage renal failure with indication for SPK transplantation in these regions.

The reasons for this variability are many and heterogenous, and often difficult to determine, but we can mention the following: differences in the incidence of type 1 diabetes according to region; lack of pancreas transplant team in some regions; distrust of the results obtained by the reference group; uncertainty about current outcomes and about the advantages of the combined transplant for the patient; or even apathy towards the preparation and follow-up of a patient who will be transplanted outside our hospital.

We have demonstrated over the years that our transplant system is exceptional. We therefore have the obligation to encourage the appropriate training, provide educational and organisational measures to correct this anomalous situation, so patients can receive what today is considered the best therapeutic option for their type 1 diabetes with end-stage renal disease.

Please cite this article as: Muñoz-Bellvís L. La extraña situación del trasplante de páncreas en España. Nefrología. 2019;39:455–457.

![ONT (Organización Nacional de Trasplantes [Spanish National Transplant Organisation]) report for 2017 on waiting list inclusions for pancreas transplantation and transplant rate PMP in the different autonomous regions. ONT (Organización Nacional de Trasplantes [Spanish National Transplant Organisation]) report for 2017 on waiting list inclusions for pancreas transplantation and transplant rate PMP in the different autonomous regions.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/20132514/0000003900000005/v1_201912172106/S2013251419301452/v1_201912172106/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w94GCRvdQBB6xyQjMrWMzrts=)