Calciphylaxis is a complication of chronic kidney disease (CKD) associated with high morbidity and mortality. Although it is rare, the use of calcium and vitamin D for the treatment of secondary hyperparathyroidism may increase the incidence of calcifilaxis. It typically presents skin ulcers with necrosis which do not heal and shows calcifications of the arterioles of the dermis and epidermis.1

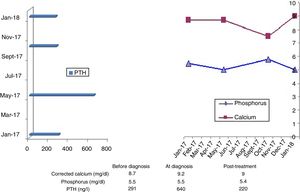

We present the case of a 76-year-old woman with a history of high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, advanced CKD, obesity and chronic venous insufficiency. As complications of CKD, she had secondary hyperparathyroidism (Fig. 1), being treated with paricalcitol and cinacalcet, and for anaemia the patient received Ferinject® and NeoRecormon®. She had recently developed a painful lesion on her ankle. Physical examination revealed a very painful necrotic plaque on the patient's left ankle, ulcerative with an erythematous halo (Fig. 2). As calciphylaxis was suspected, the patient was started on daily haemodialysis and intravenous sodium thiosulfate, paricalcitol was discontinued and additional tests were requested to confirm the diagnosis.

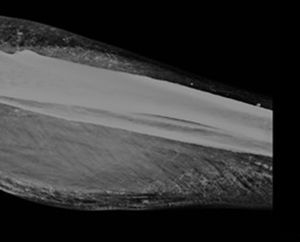

An X-ray of the affected region using the mammography technique was compatible with suspected calciphylaxis (Fig. 3), conventional ankle X-ray showed vascular calcifications (Fig. 4), and skin biopsy from the ulcer had histology of acroangiodermatitis and marked siderophagic changes, but no signs compatible with calciphylaxis. An MRI of the liver was performed to quantify iron deposition, showing evidence of moderate iron overload.

Being aware that histological data sometimes is nonspecific, and considering the medical history, physical examination and radiological findings, we continued to suspect calciphylaxis. However, the evidence of tissue iron deposition in the liver and in the skin lesion tissue led us to consider the involvement of iron overload in the pathogenesis of the lesion.

Chronic venous stasis may lead to capillary extravasation and haemoglobin catabolism that may results in free iron, which induces ferritin deposition, especially in patients with chronic venous disease and obesity,2 as was the case of our patient. Iron is also known to generate free radicals, which are involved in the pathogenesis of ulcers.

After three months of treatment with sodium thiosulfate, discontinuation of iron therapy and maintaining tight control of bone mineral metabolism (Fig. 1), the patient's ulcer was healing. At eight months, a repeat liver MRI showed the absence of iron deposition, ruling out haemochromatosis.

The multiple risk factors involved in the aetiology of calciphylaxis which have been studied do not in themselves explain the development or the severity of the condition.3,4

This case urges us to consider iron overload as a possible factor in the development of skin ulcers in patients with CKD administered IV iron, both for its known pathogenic role in producing tissue damage and its possible association with other diseases, such as calciphylaxis. It is also a warning to be careful about the indiscriminate use of intravenous iron in patients with advanced CKD.

To the Radiology and Pathology departments at Hospital Príncipe de Asturias and all the staff in the Nephrology Department.

Please cite this article as: Peña Esparragoza JK, Pérez Fernández M, Martínez Miguel P, Bouarich H. La asociación de la sobrecarga de hierro y el desarrollo de calcifilaxis. Nefrologia. 2020;40:209–210.