The treatment of renal carcinoma (CR) has been revolutionised thanks to the use of antiproliferative and immunomodulatory drugs. Sunitinib (SUN) is a tyrosine kinase (TK) inhibitor with antiproliferative and anti-angiogenic effect.1 Nivolumab (NIV) is a human monoclonal antibody, a checkpoint inhibitor, which prevents the cancer cells from evading the immune system, enhancing the patient's immune response.2 Both drugs have been shown to increase RCC survival, but have also been linked to toxicity in different organs. We describe here the case of a patient who developed renal damage associated with the use of SUN and NIV.

This was a 70-year-old male with a pacemaker due to Mobitz AV block, hypertension (HTN) and chronic kidney disease (baseline creatinine 1.4–1.5 mg/dl) due to loss of nephron mass after right nephrectomy due to RC (pT3b Nx Mx) in 2014.

After recurrence of the cancer, he received first-line treatment with SUN, which was discontinued because toxicity, including renal toxicity, leaving serum creatinine (sCr) levels of 1.4–1.8 mg/dl. Six months later, the cancer progressed, and it was decided to give a second-line treatment with NIV.

Eight weeks after the second dose of NIV, he was admitted to Medical Oncology with impaired renal function (sCr 2.8 mg/dl). Urine sediment showed albuminuria (100−200 mg/dl), leucocyturia and microhaematuria. On physical examination, the patient had crackles in lung bases and oedema to the middle third of both lower limbs. NIV was discontinued and he was started on diuretic treatment. At 48 h his renal function worsened (Crs 4.9 mg/dl), so the Nephrology Service was consulted.

After assessment by Nephrology, tests were completed with 24 h proteinuria (1.98 g/day). Obstructive uropathy was ruled out, as well as other systemic causes of acute kidney injury (AKI) (serology, autoimmunity, complement, immunoelectrophoresis, peripheral blood extension, all negative). It was decided to perform a renal biopsy to confirm possible drug-related AKI.

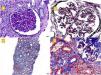

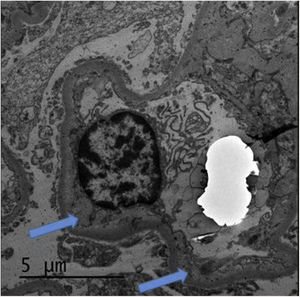

The renal biopsy (Fig. 1) confirmed the presence of interstitial lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate suggestive of acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) due to NIV. High-dose pulse steroid therapy was given over three days (250 mg on the first day and 125 mg on the second and third days), followed by oral (0.5 mg/kg) in tapering regimen, which recovered the patient's baseline Crs and reduced the proteinuria (0.8 g/day). He received prophylaxis for Pneumocystis jirovecii with Septrin. In addition, examination of the histology sample revealed segmental thickening of capillary walls with images of double contours, compatible with membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, as well as podocyte hypertrophy and chronic vascular damage with a decrease in vascular lumen of more than 75%, interstitial fibrosis and moderate tubular atrophy. Immunofluorescence showed no deposition of immunoglobulins or immune complexes, and electron microscopy (Fig. 2) confirmed enlargement of the lamina rara interna visible in thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), for which these lesions were attributed to the previous treatment with SUN.

A) Glomerulus with reinforcement of the glomerular pattern, mesangial cell proliferation and thickening of the capillary walls. PAS, 40 × . B) Double contour images (marked with arrows). Silver technique. C) Moderate fibrosis, tubular atrophy and lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates in the interstitium. Masson, 40 × . D) Arterioles with smooth muscle hyperplasia and decreased lumen. Masson.

It is known that the administration of anti-angiogenic drugs, such as SUN, may cause HTN, proteinuria and TMA.1,3 There have even been cases recently reported of AIN in association with these medications.4 The histology sample showed images of double contours, podocyte hypertrophy and decrease in vascular lumen, characteristic of TMA and associated with the use of SUN.3

AKI associated with checkpoint inhibitors has also been described.5,6 It generally occurs three to six months after the first dose and patients have leucocyturia and non-nephrotic proteinuria.5 The characteristic histology finding is the presence of infiltrate in the interstitium.6 Cortazar et al. recently described a series of 12 patients with tubulointerstitial nephritis associated with the use of checkpoint inhibitors.6 Unlike the AIN induced by other drugs, in which the infiltrate is usually formed by eosinophils, in this case, the infiltrate is mainly of lymphocytes. This may be the result of a different mechanism, deriving from a "reprogramming" of the immune system leading to a loss of tolerance against endogenous antigens in the kidneys, which would also explain the latency period between administration and onset of the adverse effect.6

The treatment in both cases is discontinuation of the drug that is causing the kidney damage. In the case of the NIV-induced AIN, the use of corticosteroids has been shown to recover renal function in most situations.5,6

One important question is whether a patient who has had kidney damage induced by these drugs should receive the medication again. Most series recommend complete discontinuation if toxicity reaches grade III-IV, or if haemodialysis is required.5,6 A balance needs to be made between the oncological benefits of continuing treatment and the risk of recurrence of the kidney disease. Therefore, we recommend close monitoring of the patient, including monitoring of renal function and blood pressure, in order to be able to act quickly and avoid irreversible damage.

Please cite this article as: Moliz C, Cavero T, Morales E, Gutiérrez E, Alonso M, Praga M. Fracaso renal agudo asociado a inhibidores check-point. Nefrologia. 2020;40:206–208.