The recent appearance of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus pandemic has had a significant impact on the general population. Patients on renal replacement therapy (RRT) have not been unaware of this situation and due to their characteristics they are especially vulnerable. We present the results of the analysis of the COVID-19 Registry of the Spanish Society of Nephrology.

Material and methodsThe Registry began operating on March 18th, 2020. It collects epidemiological variables, contagion and diagnosis data, signs and symptoms, treatments and outcomes. It is an online registry. Patients were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection based on the results of the PCR of the virus, carried out both in patients who had manifested compatible symptoms or had suspicious signs, as well as in those who had undergone screening after some contact acquainted with another patient.

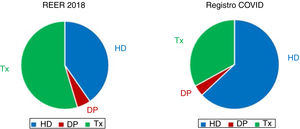

ResultsAs of April 11, the Registry had data on 868 patients, from all the Autonomous Communities. The most represented form of RRT is in-center hemodialysis (ICH) followed by transplant patients. Symptoms are similar to the general population. A very high percentage (85%) required hospital admission, 8% in intensive care units. The most used treatments were hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir–ritonavir, and steroids. Mortality is high and reaches 23%; deceased patients were more frequently on ICH, developed pneumonia more frequently, and received less frequently lopinavir–ritonavir and steroids. Age and pneumonia were independently associated with the risk of death.

ConclusionsSARS-CoV-2 infection already affects a significant number of Spanish patients on RRT, mainly those on ICH, hospitalization rates are very high and mortality is high; age and the development of pneumonia are factors associated with mortality.

La reciente aparición de la pandemia por el coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 ha impactado de forma muy importante en la población general. Los pacientes en tratamiento renal sustitutivo (TRS) no han sido ajenos a esta situación y por sus características resultan especialmente vulnerables. Presentamos los resultados del análisis del Registro COVID-19 de la Sociedad Española de Nefrología.

Material y métodosEL Registro comenzó a funcionar el 18 de marzo de 2020. Recoge variables epidemiológicas, datos del contagio y diagnóstico, clínica acompañante, tratamientos y desenlace. Se trata de un registro on line. Los pacientes fueron diagnosticados de infección por SARS-CoV-2 en base a los resultados de la PCR del virus, realizada tanto en pacientes que habían manifestado clínica compatible o tenían signos sospechosos como en aquellos a los que se había hecho como cribado tras algún contacto conocido con otro enfermo.

ResultadosA fecha 11 de abril el Registro disponía de datos de 868 pacientes, procedentes de todas las comunidades autónomas. La modalidad de TRS más representada es la hemodiálisis en centro (HDC) seguida de los pacientes trasplantados. La clínica de presentación es similar a la población general. Un porcentaje muy elevado (85%) requirió ingreso hospitalario, un 8% en unidades de cuidados intensivos. Los tratamientos más utilizados fueron hidroxicloroquina, lopinavir-ritonavir y esteroides. La mortalidad es elevada y alcanza el 23%: los pacientes fallecidos estaban con más frecuencia en HDC, desarrollaban más frecuentemente neumonía y recibían en menos ocasiones lopinavir-ritonavir y esteroides. La edad y la neumonía se asociaban de forma independiente al riesgo de fallecer.

ConclusionesLa infección por SARS-CoV-2 afecta ya a un número importante de pacientes españoles en TRS, fundamentalmente aquellos que están en HDC, las tasas de hospitalización son muy elevadas y la mortalidad es elevada; la edad y el desarrollo de neumonía son factores asociados a mortalidad.

In late 2019, the Authorities from People's Republic of China reported to the World Health Organization several cases of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, a city located in the Chinese province of Hubei. Later, it was found that it was an infection caused by a new coronavirus called SARS-CoV-2. This virus causes various clinical manifestations included under the term COVCID-19, including respiratory symptoms of different severity, from a common cold to severe pneumonia with respiratory distress syndrome, septic shock and multiple organ failure.

Since then, the virus has been spreading throughout the world, and to date, almost 2 million people are contaminated.1 At April 11, 2020, United States is the country with the most confirmed cases, followed by Spain, Italy, Germany and France.1

The emergence of this pandemic has demanded a special care to more vulnerable groups of people. Among these are chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients, especially those that require renal replacement therapy (RRT).

Since the beginning of this pandemic, the Spanish Society of Nephrology (SEN) started to work together with the Ministry of Health, Nephrology services across the country, patients’ associations and other scientific societies. The idea was to develop contingence plans and specific protocols to gain information and knowledge on this new and very serious disease.

One of the first projects developed during the first weeks of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic affecting Spain was the generation of a specific Registry of patients in some form of RRT in Spain. This collective effort resulted in the “SEN Registry of COVID-19”. The objective of this manuscript is to present the results of the first analysis of this Registry at week 3 of data collection.

Material and methodsThe COVID-19 Registry began operating on March 18, 2020. The week before, a committee of experts was created to decide which variables should be included in the registry. The selection of variables to generate a Registry is not immediate a simple. It is desirable to incorporate as many variables as possible to acquire a large amount of information. However complexity is a drawback, the greater the number of variables, the lower the degree of implementation. Furthermore, currently Nephrologists and Nephrology Services are under a high demand and even a significant number of professionals are affected by the coronavirus. For this reason, it was decided to choose the minimum set of variables that would give us a perspective of the impact that the SARS CoV-2 pandemic in patients on RRT in Spain. Furthermore, the information to be collected should be in line with the Registry of the European Renal Association – European Dialysis and Transplant Association (ERA-EDTA) so that eventually data could be unified at European level.

After satisfying all these demands, epidemiological variables, modalities of renal replacement therapy, contagion information, diagnosis data, accompanying symptoms, treatments and outcome were included in the Registry. This is an anonymous Registry that meets the requirements imposed by legislation. Authorization for its operation was requested from the Regional Ethical Committee of the Principality of Asturias.

The COVID-19 Registry of the SEN has a format “on line” with access through the website of the Society (www.senefro.org) after the prior identification of the person having access to the site. Each user of the Registry has access to the patient data they have entered, but not to the rest of the information. The complete database can only be managed by the coordinator of the Registry or any other member of the SEN upon written request and prior authorization from the experts committee. The patients were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection based on the PCR results, carried on the patient with symptoms suggestive of infection, or as screening after contact with another infected patient.

The Registry will remain operational as long as the current coronavirus pandemic situation is maintained. Periodic analyzes of the information recorded will be carried out to obtain conclusions about the impact of this infection on RRT patients in Spain and the effect of different strategies dealing with this disease. The results presented here correspond to the analysis of the data recorded until April 11, 2020.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation and categorical variables as percentage. Baseline values were compared using T test and Chi Square as appropriate. The KoImogorov–Smirnov test had been used to determine if data is normally distributed. Linear or logistic regression models were used to know the factors associated with mortality. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. The statistical package SPSS 20® for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used to analyze the results.

ResultsAs of April 11, data from 868 patients on RRT with documented SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus infection had been entered into the Registry. Patients were from 103 health centers scattered throughout Spain. All regions so called Autonomous Communities, have reported cases (Table 1), Madrid presented the largest number of cases (36%), followed by Catalonia (18%), Castilla La Mancha (12%) and Andalusia (9%). The average age of the infected patients is 67±15 years and two thirds are male.

Distribution of registered cases by Autonomous Community.

| Autonomous community | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| Madrid's community | 35.8 |

| Catalonia | 18.0 |

| Castilla la Mancha | 12.0 |

| Andalusia | 8.5 |

| Valencian Community | 6.0 |

| Basque Country | 5.1 |

| Castilla y León | 3.1 |

| Navarre | 3.0 |

| Galicia | 1.8 |

| Balearic Islands | 1.6 |

| Estremadura | 1.4 |

| Aragon | 1.0 |

| Canary Islands | 1.0 |

| Principality of Asturias | 0.6 |

| The Rioja | 0.5 |

| Murcia region | 0.3 |

| Cantabria | 0.2 |

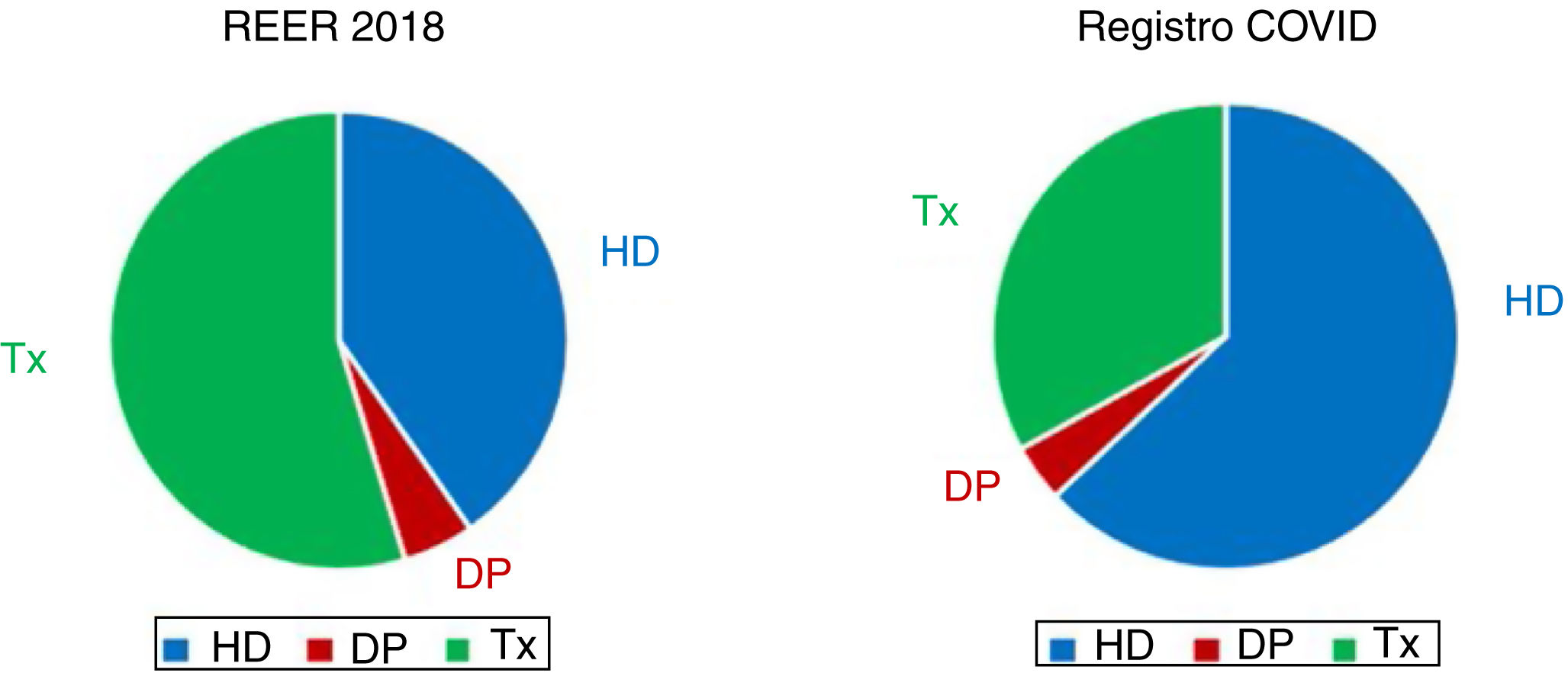

Most SARS-CoV-2 patients are from hemodialysis centers (HDC) (63%), followed by transplant patients (TX) (33%) and much less common are peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients (4%). There have been reported two cases on home hemodialysis (HHD) (Fig. 1).

Three out of ten infected patients had had known prior contact with someone else infected. This percentage slightly rose to 34% in the case of patients on HDC, being 24% on PD and 22% in the case of TX patients. The average incubation period, in those patients with known prior contact, was 7±4 days.

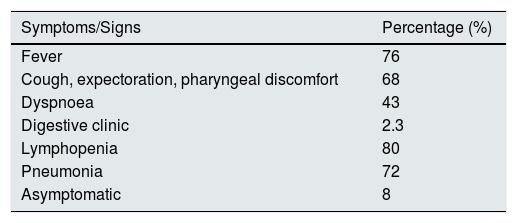

Regarding clinical manifestations (Table 2), 3 out of 4 patients had fever, two-thirds had symptoms of upper respiratory infection and 43% dyspnea. Almost a quarter had gastrointestinal symptoms. Only 8% were asymptomatic. The most frequent complication developed was pneumonia in 72% of patients, and a 80% also had lymphopenia.

A very high percentage of registered patients (85%) required hospital admission, and 8% had to be admitted in the Intensive Care Units (ICU), of these almost two thirds required mechanical ventilation. The average length of hospital admission (contemplating only cured patients) was 10±4 days.

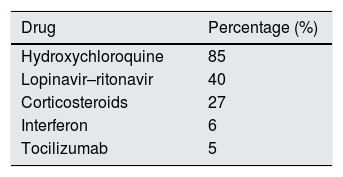

The most commonly used treatments (Table 3) were the hydroxychloroquine (85%) and the combination of lopinavir–ritonavir (40%). A third of the patients received the 3 drugs together. Steroids, interferon and tocilizumab used were less frequently.

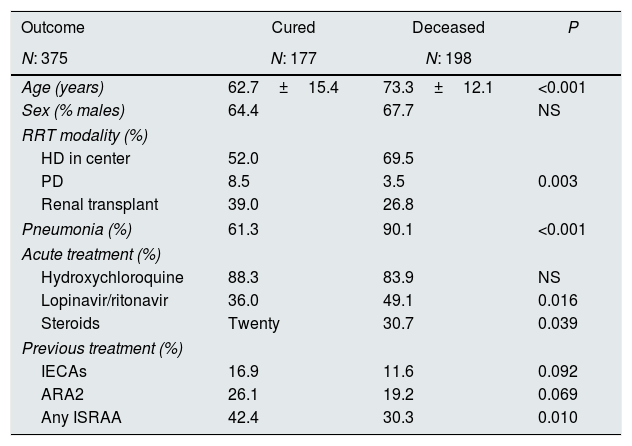

To date, 198 patients have died (a 23% of the registered patients). The characteristics of these patients are reflected in Table 4. As compared with cured patients, deceased were older, were more often from HDC, developed more frequently pneumonia, were more frequently on lopinavir–ritonavir and steroids and had been prescribed less frequently renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors before infection.

Patient characteristics depending on the outcome.

| Outcome | Cured | Deceased | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| N: 375 | N: 177 | N: 198 | |

| Age (years) | 62.7±15.4 | 73.3±12.1 | <0.001 |

| Sex (% males) | 64.4 | 67.7 | NS |

| RRT modality (%) | |||

| HD in center | 52.0 | 69.5 | |

| PD | 8.5 | 3.5 | 0.003 |

| Renal transplant | 39.0 | 26.8 | |

| Pneumonia (%) | 61.3 | 90.1 | <0.001 |

| Acute treatment (%) | |||

| Hydroxychloroquine | 88.3 | 83.9 | NS |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | 36.0 | 49.1 | 0.016 |

| Steroids | Twenty | 30.7 | 0.039 |

| Previous treatment (%) | |||

| IECAs | 16.9 | 11.6 | 0.092 |

| ARA2 | 26.1 | 19.2 | 0.069 |

| Any ISRAA | 42.4 | 30.3 | 0.010 |

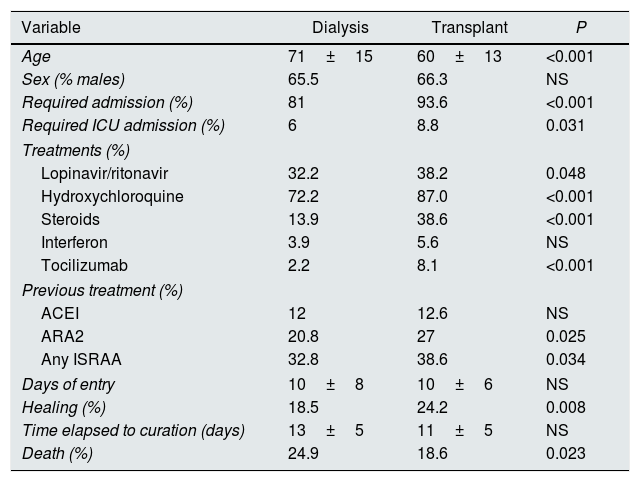

The characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 patients from Dialysis (including HDC, HHD, and PD) and transplant were different (Table 5). The transplanted patients were younger, with more frequent hospital admissions both in the ward and in ICU, they developed more pneumonia and a greater number of transplant patients were treated with lopinavir–ritonavir, hidroxychloroquine, steroids, and tocilizumab; they also had received RAAS inhibitors more frequently before being infected. Finally, percent of deaths were less in transplant than in dialysis patients.

Comparison of dialysis (including center HD, home HD and PD) vs transplant.

| Variable | Dialysis | Transplant | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 71±15 | 60±13 | <0.001 |

| Sex (% males) | 65.5 | 66.3 | NS |

| Required admission (%) | 81 | 93.6 | <0.001 |

| Required ICU admission (%) | 6 | 8.8 | 0.031 |

| Treatments (%) | |||

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | 32.2 | 38.2 | 0.048 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 72.2 | 87.0 | <0.001 |

| Steroids | 13.9 | 38.6 | <0.001 |

| Interferon | 3.9 | 5.6 | NS |

| Tocilizumab | 2.2 | 8.1 | <0.001 |

| Previous treatment (%) | |||

| ACEI | 12 | 12.6 | NS |

| ARA2 | 20.8 | 27 | 0.025 |

| Any ISRAA | 32.8 | 38.6 | 0.034 |

| Days of entry | 10±8 | 10±6 | NS |

| Healing (%) | 18.5 | 24.2 | 0.008 |

| Time elapsed to curation (days) | 13±5 | 11±5 | NS |

| Death (%) | 24.9 | 18.6 | 0.023 |

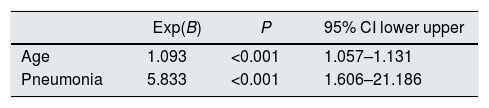

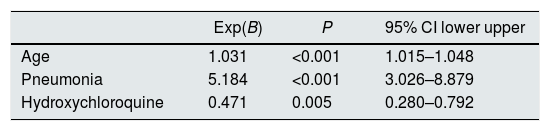

We analyzed the factors associated with mortality in transplant and dialysis patients. In transplant patients, age and development of pneumonia were independently associated with mortality (Table 6). As for dialysis patients, again age and pneumonia were factors associated with mortality but it was also found a beneficial effect of hydroxychloroquine (Table 7).

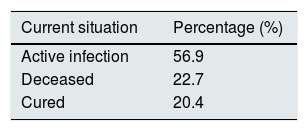

Finally, the cure of the infection has been reported in 20% of patients; the average time elapsed before curation was 12±5 days. A 22.7% of patients died and the rest remained in a situation of active infection (Table 8).

DiscussionThe analysis of data collected during the first three weeks of the Covid-19 Registry of SEN shows that the SARS-CoV-2 infection affects a significant number of Spanish patients on RRT, mainly those that are in HDC. The rate of hospital admissions are very high and the mortality is elevated; age and the development of pneumonia are risk factors for mortality, while the use of hydroxychloroquine could have had a protective effect, at least in dialysis patients.

In Spain, SARS-CoV-2 infection has spread throughout all the Autonomous Communities. According to data supplied by the Ministry of Health2 the incidence has been particularly high in Madrid, Catalonia, Castilla La Mancha and Castilla y León. Similarly, and according to the data from the SEN Registry, infected patients on RRT are mainly from these regions, although Castilla y León has reported fewer cases than they would correspond due to their global number of infections. Communities with the lowest overall number of infections, such as Cantabria, Murcia, Extremadura, the Canary Islands and the Principality of Asturias, have also reported a lower number of SARS-CoV-2 patients on RRT.

The mean age of patients infected match the mean age of the patients on RRT. As in the entire population on RRT, infected HD patients were also significantly older than transplant or PD patients. In the general population, it appears that the coronavirus affects more males than females. In the case of patients on RRT, there are also more men infected, but this could reflect the greater number of men in the RRT programs.

Despite the fact that more than half of the Spanish patients on RRT are transplanted,3 the spread of SARS-CoV-2 is more frequent in patients from HD centers. This fact may not by surprising because HD patients failed to fulfill the regulatory confinement since they have to move to the hospitals and dialysis centers 3 or more times per week and not infrequently they have to use public transportation. Moreover, a number patients undergoing HDC live in nursing homes, a place of frequent infections. Despite immunosuppression, transplant patients, represent only one third of the registered infected patients. Finally it should be noted that patients on peritoneal dialysis, and especially those in HHD, represent a very low rate of infected patients, although their representation in the total of RRT patients in Spain is relatively low.3

As far as clinical manifestations, there are no differences with what has been reported in the general population. Most frequent manifestations were fever and the symptoms of upper respiratory infection. These same symptoms and with a similar frequency were observed in a retrospective study including almost 1100 patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection not in RRT.4 A quarter of our patients also reported gastrointestinal symptoms which is more frequent than in the general population as shown in the previously mentioned study.4 By contrast, other authors show a rate of gastrointestinal symptoms that is even higher than in our patients.5 Moreover, the first case of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a hemodialysis patient in the United States, presented with diarrhea as the first symptom of the infection.6 The different forms of screening or diagnosis in the population may be the cause of nonuniform results.

Hospitalization rates in our patients are very high, exceeding 80% of cases. Published studies in the general population reveal considerably lower rates of hospitalization;7 however it should be taken into consideration that patients in RRT are older and with more comorbidities whichundoubtedly results in a more deteriorated clinical situation. Just three weeks ago, the results of a meta-analysis that included 4 published studies and 1400 patients were published and concluded that chronic kidney disease was a risk factor for developing a more severe SARS-CoV-2 infection.8 One of the possible explanations why CKD have a worse prognosis lies in the role that T lymphocytes on the recovery from infection.9 It is known that in uremia there is a deterioration in lymphocytes and granulocytes function which may alter the defense mechanisms against the virus.10

Hospital admission were more frequent among transplanted patients as compared with those on dialysis; and, they also have more admission in ICUs. It seems that immunosuppression could play a role.11

The mortality is high, above 20%. Dialysis patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection have a higher risk of dying than transplant patients, this circumstance is probably related to older age and comorbidity (a variable not recorded in the Registry). In the last report from the Ministry of Health, April 13th2 mortality in the age group of 70–79 years was 13.9%, half of what we found in our dialysis patients Registry. The high risk of complications in patients on RRT must be taken into consideration. The analysis of factors independently associated with the risk of death show that age and the development of pneumonia determine a worse prognosis. Furthermore, in the group of patients on dialysis, the use of hydroxychloroquine is associated with a lower rate of deaths; however, the significance of this last finding requires studies in a larger number of patients. Presently there is controversy about the beneficial effect of hydroxychloroquine. In in vitro studies, this drug has shown activity against various viruses, including coronaviruses and influenza.12 A French study, found some benefit from its use but number of patients was limited;13 by contrast, another study from China does not find that patients treated with hydroxychloroquine have better recovery rates.14 In our study, the beneficial effect of hydroxychloroquine is found in dialysis, but not in transplant patients. Nevertheless our registry show that, hydroxychloroquine and other commonly used drugs in the SARS-CoV infection-2 are used more frequently in transplant than in dialysis patients. Ongoing controlled studies will show if the use of these drugs is beneficial.

The benefit of RAAS inhibitors is controversial. Some of the initial publications warned about the possibility that the use of these drugs (indicated in the treatment of hypertension, heart failure, ischemic heart disease, etc.) may increase the risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2. The rational is that, to infect cells virus binds to Angiotensin II converting enzyme (ACE 2), and this enzyme appears to be overexpressed in subjects on ACE inhibitors or Angiotensin II receptor antagonist (ARA 2).15 However, experiment in animals models have suggested that the use of ARA2 can mitigate infection by attenuating Angiotensin II-mediated acute lung injury by blocking the Angiotensin II type 1 receptor.16 A recent meta-analysis suggests a beneficial effect of ARA 2 on the severity of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in elderly patients.17 For all these reasons, the health authorities recommend maintaining the indication of these drugs.18

At the time of the present report there was only a 3 week period of data collection in this Registry, 20% of cases are cured and 60% are shown as active infection. In the coming weeks will know the final outcome of all these patients. This information will provide more knowledge on the effects of SARS-CoV-2 in RRT patients.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This work would not have been possible without the participation of many colleagues who have collaborated in different manners in the collection and analysis this data. The names of all of the collaborators are shown in Annex 1.

Roberto Alcázar, Alberto Ortiz, AL Martín de Francisco, Mercedes Salgueira Lazo, Ainhoa Hernando Rubio, Alberto Rodríguez Benot, Alejandro Pérez Alba, Alex Gutiérrez Dalmau, Alfonso Cubas Alcaraz, Alfonso Pobes Martínez de Salinas, Amir Shabaka Fernández, Ana Roca Muñoz, Ana Isabel Martínez Díaz, Anabertha Narváez Benítez, Andrés Villegas Fuentes, Aniana Oliet Palá, Anna Buxeda I Porras, Antonio Franco Esteve, Antonio Gascón Mariño, Armando Coca Rojo, Auxiliadora Mazuecos, Beatriz Díez Ojea, Beatriz María Durá Gúrpide, Belén Gómez Giralda, Belén Moragrega, Boris Gonzales Candia, Bruna Natacha Leite Costa, Carlos Antonio Soto Montáñez, Carmen Gómez Roldán, Carola Arcal Cunillera, Cassandra Emma Puig Hooper, Celestino Piñera Haces, Concepción Álamo Caballero, Cristina Canal Girol, Cristina Galeano Álvarez, Cristina Ruiz González, Daniel Eduardo Villa Hurtado, Diego Rodríguez Puyol, Eduardo Muñoz De Bustillo Llorente, Elena Calvo, Elena Castillón Lavilla, Elena Giménez Civera, Elena Vaquero Párrizas, Enrique Peláez Pérez, Fernando Fernández Girón, Fernando Simal Blanco, Fernando Tornero Molina, Francisco Javier Ahijado Hormigos, Gabriel Bernal Blanco, Gema Velasco Barrero, Hernando Trujillo Cuéllar, Isabel Beneyto Castelló, Isabel García Méndez, Isabel María Saura Luján, Jaime Sanz García, Jary Perelló Martínez, Javier Arrieta Lezama, Jesús Grande Villoria, Joan Manuel Gascó Company, Joaquín de Juan Ribera, Joaquín Manrique Escola, Jorge Reichert, Juan Carlos Martínez Ocaña, Juan Carlos Ruiz San Millán, Juan Cristobal Santacruz Mancheno, Juan Manuel Buades Fuster, Laura Espinosa Román, Laureano Pérez Oller, Luis Alberto Sánchez Cámara, Luis Fernando Domínguez Reina, Luis Gil Sacaluga, Luz María Cuiña Barja, María José Soler Romeo, María del Carmen Fraile Marcos, María Dolores Prados Garrido, María José Fernández-Reyes Luis, María Teresa Naya Nieto, María Victoria Guijarro Abad, María Carmen Ruiz Fuentes, María Auxiliadora Bajo Rubio, María de los Ángeles Rodríguez Pérez, María del Mar Rodríguez de Oña, María Esperanza Moral Berrio, María Gabriela Sánchez Márquez, María Isabel Jimeno Martín, María Jesús Castro Vilanova, María Jiménez Herrero, María Lourdes Pérez Tamajón, María Luisa Suárez Fernández, María Ovidia López Oliva, María Pérez Fernández, María Pilar Pérez del Barrio, Maria Sánchez Sánchez, María Teresa Rodrigo de Tomás, María Teresa García Falcón, Mariana Garbiras, Marta Sánchez Heras, Martín Giorgi González, Mercedes Cabello Díaz, Miguel Angel Suarez Santisteban, Miguel Rodeles del Pozo, Milagros Fernández Lucas, Nuria García Fernández, Orlando Siverio Morales, Pablo Castro de la Nuez, Paloma Leticia Martín Moreno, Patricia de Sequera Ortiz, Paula Munguía Navarro, R. Alvarez, Rafael García Maset, Ramón Jesús Devesa Such, Raquel Díaz Mancebo, Raquel Santana Estupiñán, Roberto Holgado Salado, Rodrigo Avellaneda Campos, Rosa Maria Ruiz-Calero Cendrero, Rosa Sánchez Hernández, Sandra Beltrán Catalán, Sheila Cabello Pelegrín, Silvia Benito García, Silvia González Sanchidrián, Silvia Ros Ruiz, Sofía Zárraga Larrondo, Teresa Bada Bosch, Verónica López Jiménez, Yanina García Marcote.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez-Álvarez JE, Fontán MP, Martín CJ, Pelícano MB, Reina CJ, Prieto ÁM, et al. Situación de la infección por SARS-CoV-2 en pacientes en tratamiento renal sustitutivo. Informe del Registro COVID-19 de la Sociedad Española de Nefrología (S.E.N.). Nefrologia. 2020;40:272–278.