INTRODUCTION

Reflecting on the various vicissitudes that the Spanish Society of Nephrology¿s (SEN) dialysis and transplant report has taken throughout its history,1 the present report is the result of a collective effort by several institutions ¿ the SEN, Autonomous Communities renal patient registries, regional nephrology societies, Autonomous Communities transplantcoordinating bodies and the Spanish National Transplant Organisation (ONT) ¿ to unify criteria, combine efforts and obtain information on a national scale that would be representative of the treatment situation for terminal chronic kidney disease (CKD) in Spain by creating a national renal patient registry.

This registry¿s formative process began at the meeting with the Inter-territorial Council of the Spanish National Health Care System¿s Transplant Commission on 4 May 2005 when the SEN¿s Board of Directors raised the possibility of the National Transplant Organisation (ONT) beginning to coordinate the information generated by Autonomous Communities renal patient registries and supporting creation of such registries in those Autonomous Communities (ACs) in which none exist.

Throughout 2006, meetings were held between the ONT, the SEN, the effective Autonomous Communities registries and representatives from Autonomous Communities lacking a registry to create the Spanish Registry of Renal Patients. It was created with a Registry Committee and a Scientific Committee formed by the ONT, representatives from Autonomous Communities registries and the SEN by means of a dialysis and transplant registry coordinator. In this way, it makes use of all of the work carried out in previous years by the Registry of Renal Patients Group (GRER),2 in which the SEN and some AC registries were already participating, thus integrating these components into the new structure and inheriting its methodology and data series. The registry¿s technical secretariat will report to the ONT, which will own the rights to the automated data file for the national registry and will therefore be responsible for its maintenance. The national database was created by combining the data provided by each registry.

In this way, the Spanish Registry of Renal Patients becomes a referent for the accumulated information about treating terminal CKD in Spain, both for health care professionals and for different governments and national or international institutions. Over the last three years, the Spanish Registry of Renal Patients has presented the preliminary reports on dialysis and transplant activities in Spain in 2006 and 2007 at the 2007 and 2008 SEN Congresses (in Cádiz and San Sebastián respectively), and has been the source of national information for the European registry ERA-EDTA3,4 and for the USRDS in the United States.5,6

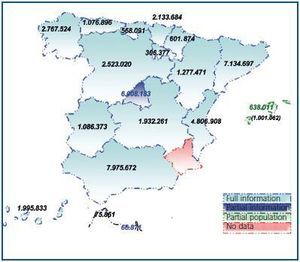

Although it comes somewhat late, and despite having some methodological difficulties due to process of developing some AC registries, this report offers information regarding 96.1% of the Spanish population. It contains data provided by 16 out of 17 ACs and the Autonomous Cities of Ceuta and Melilla through the Autonomous Communities registries of renal patients, and with information from regional nephrology societies and transplant coordinating bodies for ACs whose registries have not yet been set up, in addition to data from the ONT¿s donation and transplant registries.

DATA SOURCES AND POPULATION COVERAGE

The total population covered by this report is 42,975,607 inhabitants, comprising 96.1% of the 44,708,964 inhabitants reflected by municipal registries on 1 January 2006.7

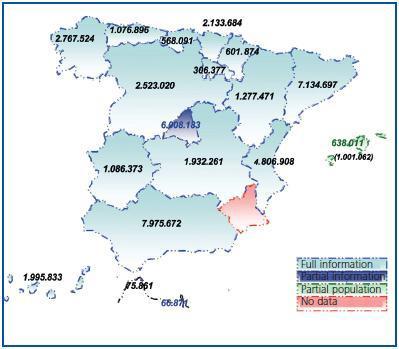

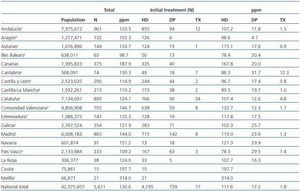

Information was provided by the Autonomous Communities registries for Andalusia (including the registry for the city of Ceuta), Asturias, Aragón, the Canary Islands, Cantabria, Castile and Leon, Castile-La Mancha, Catalonia, the Valencian Community, Extremadura, Galicia and the Basque Country. This population comes to 35,354,291 people, or 79.1% of the national total, or 82.3% of the population reflected in this report. The Navarre transplant coordination unit was the source of data for that Community, and the Rioja Society of Nephrology provided data for La Rioja. Balearic Islands data were provided by that AC¿s transplant coordination unit, and only include information from four centres that correspond to a population of 638,011 inhabitants, that is, 63.7% of the AC¿s total population. The Madrid Society of Nephrology provided data for Madrid; these were gathered by the company COHS from nephrology divisions and dialysis centres and units. Only global data is provided which is not broken down by sex, age or primary kidney disease (PKD). Likewise, INGESA provided data from the Melilla nephrology unit as global data not broken down by sex, age or PKD (figure 1).

Transplant numbers, types and centres where performed in 2006 were obtained from the ONT registry, which covers 100% of the Spanish population.

METHODOLOGY

The data collection method for accumulated data is the same as that used for previous reports,1,8 uses Excel spreadsheet formulas and is specific to each Autonomous Community.

The definitions in use have been determined by consensus within the Registry of Renal Patients Group (GRER) and are listed in the Common Criteria document.9

The form records overall incidence data broken down by treatment method: haemodialysis (HD), peritoneal dialysis (PD) and upcoming transplant (TX); total transplants and live-donor transplants performed in 2006; prevalence on 31 December 2006 per treatment mode on that date: in-centre HD, HD at home, CAPD, cycler-assisted PD and functioning TX; prevalent patient on dialysis with HIV seromarkers (HIV+), the hepatitis B antigen (HBV+) and hepatitis C antibodies (HCV+); patients who return to haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis after losing the graft within the year, and the total number of deaths in 2006 of patients whose last treatment was HD, PD or TX.

Additionally, we recorded the number of incident patients in 2006, broken down by age range and gender, age range and primary kidney disease (PKD), and by age range and initial treatment method. Prevalent patients as of 31 December were also broken down by age range and gender; gender, age range and PKD, and age range and treatment method.

The mortality figures were broken down by different treatment methods at the time of death (HD, PD and TX), by age group and cause of death.

The form uses several verification procedures for the data that is entered, which enables it to detect inconsistencies and partial omissions by comparing global data with grouped data.

Once the forms are received, the data is integrated and validated by comparing it with data from previous years and alternative sources. For transplants, the numbers received are compared with the ONT records; this is the source used to detect discrepancies.

Lastly, the breakdown of different types of kidney transplant is obtained from ONT records.10

INCIDENCE

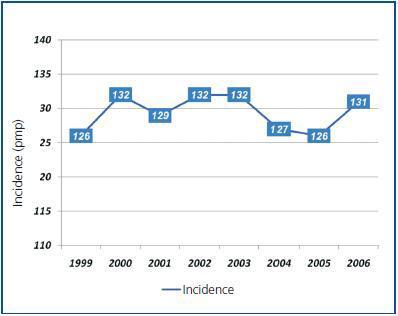

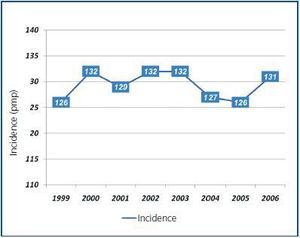

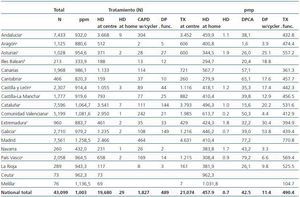

During 2006, 5,611 patients began kidney replacement therapy in those Spanish Autonomous Communities which provided information. This reflects a rate of 130.6 patients per million population (ppm), or 148.6 ppm if we consider only the population older than 14 years. The global incidence rate is stable (figure 2) with respect to previous years,1,8,11-13 and there is a large degree of variance between Autonomous Communities; rates range from 103.3 ppm in Aragón to 187.9 ppm in the Canary Islands (table 1).

85.5% of patients who began treatment in 2006 underwent HD, 13.2% began treatment on PD, and only 1.37% received TX as an initial treatment.

There were 1.74 times more male patients than female patients beginning treatment. Logically enough, there was a higher incidence rate among more elderly patient groups, which reached 403 ppm in the 65-74 age group and 413 in the over-75 age group.

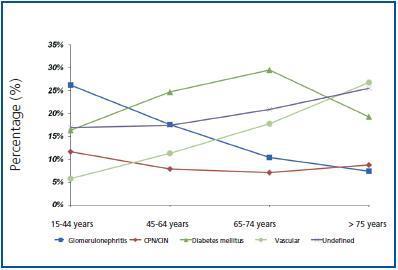

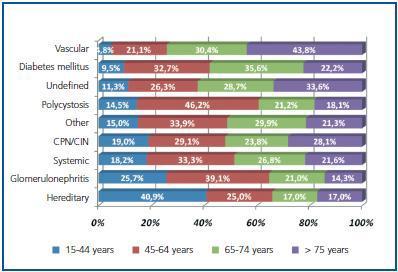

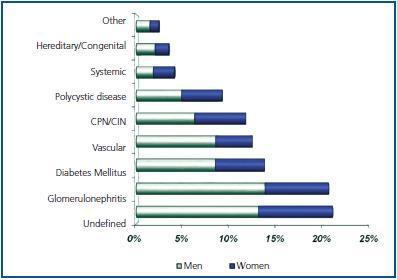

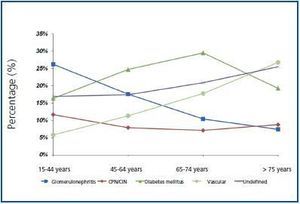

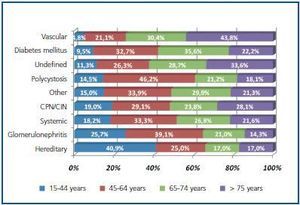

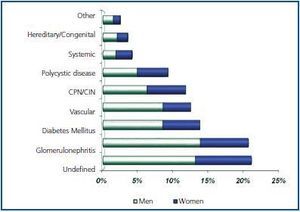

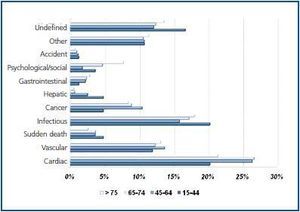

Of the 4,701 patients listed by the records and grouped by primary kidney disease (PKD), 1,102 had diabetes mellitus as a PKD, which at 23.4% was the most frequent cause of kidney disease in the 45-64 and 65-74 age groups. It was also the cause of PKD in 46.7% of patients in the Canary Islands (87.7 ppm) and Ceuta (92.3 ppm). On the other hand, as stated in previous reports, there is still a very high percentage of undetermined PKD (20.5%). In the group of patients over 75, PKD was most commonly classified as ¿Vascular¿ (26.7%), followed by ¿Undetermined¿ (25.5%) (figure 3) and 43.8% of PKD classified as ¿Vascular¿ corresponded to patients older than 75 (figure 4).

PREVALENCE

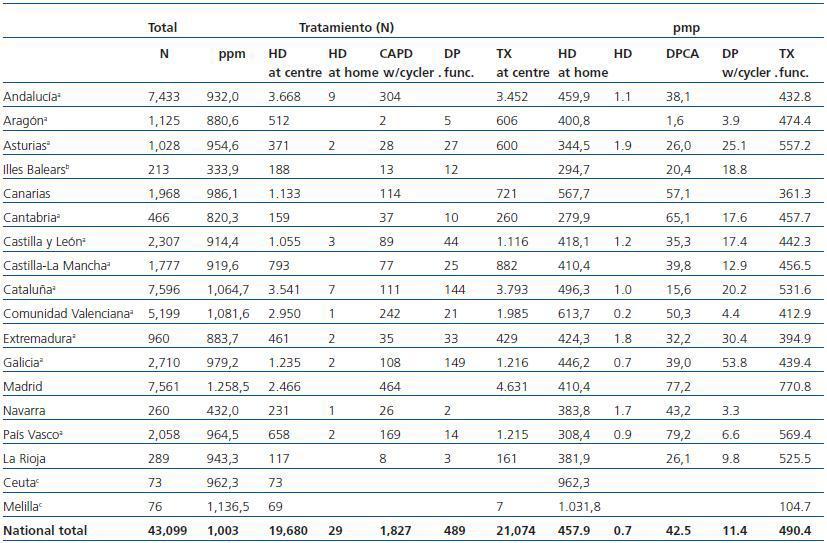

On 31 December 2006, according to information received from the abovementioned sources, 43,099 patients received treatment for terminal CKD within the area covered by the report. This is the first time the prevalence, 1,003 patients per million, has risen to four digits, although there may be biases which overestimate the number of transplant patients in some Autonomous Communities. At the same time, others have not provided information. There were 1.58 males per female undergoing treatment; this varied widely between Autonomous Communities. The overall breakdown by treatment method was HD 45.7%, PD 5.4% and functioning TX 48.9%. There are variations in treatment method from Community to Community, fundamentally affecting the percentage of patients on PD and receiving transplants (table 2).

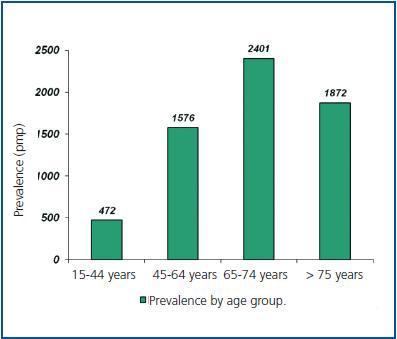

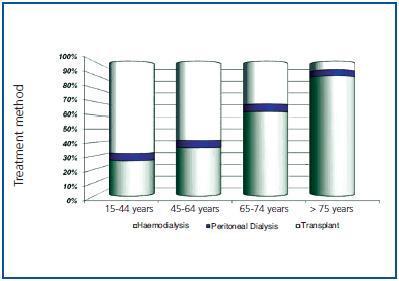

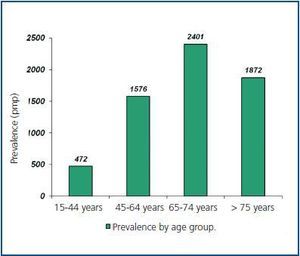

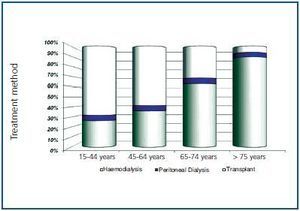

The highest prevalence rate was for patients in the 65 to 74 age group (figure 5), and the numbers were higher than those shown by previous reports.1 The prevalence rates for the different treatment types also vary according to age groups. Transplants are more prevalent among younger patients and HD prevalence increases with age; 68% of patients aged 15 to 45 have a functioning TX compared with only 6% in patients over 75. However, only 5% of patients receive treatment with PD, which is consistent from age group to age group (figure 6).

The highest percentage of total prevalent patients, 21.3%, was classified as having an undetermined cause of PKD; glomerulonephritis accounted for 20.9% and diabetes mellitus, 13.9% (figure 7).

Of the patients undergoing different types of treatment with HD or PD, 1.61% was seropositive for the hepatitis B surface antigen, 8.54% was HCV-positive and 0.91% was HIV-positive.

KIDNEY TRANSPLANT

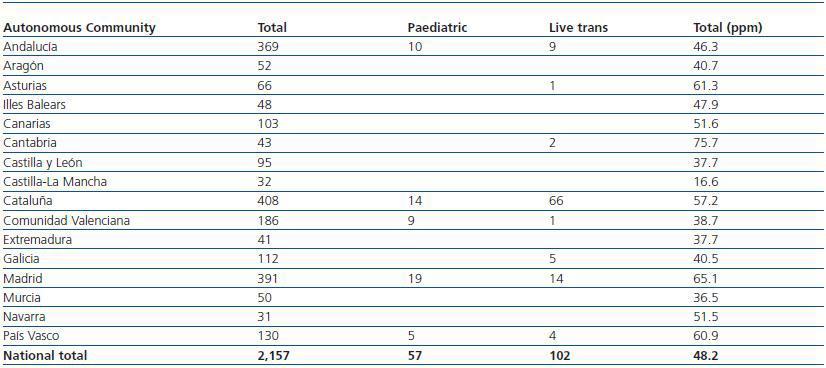

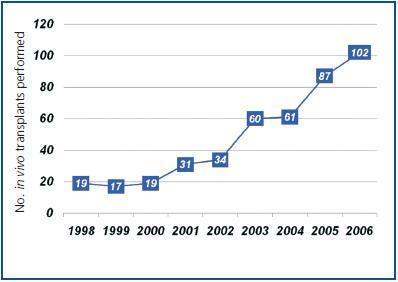

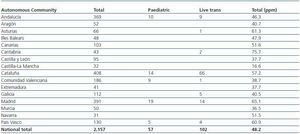

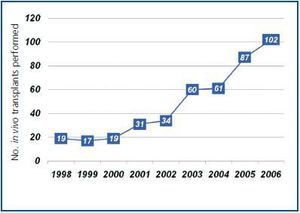

In 2006, 2,157 kidney transplants were performed in Spain, of which 57 were in children and 102 came from a live donor (table 3). These two figures, which have been increasing since the beginning of the decade, continue to rise (figure 8).

Meanwhile, also in 2006, 533 patients returned to dialysis (476 HD and 57 PD) due to loss of the graft.

MORTALITY

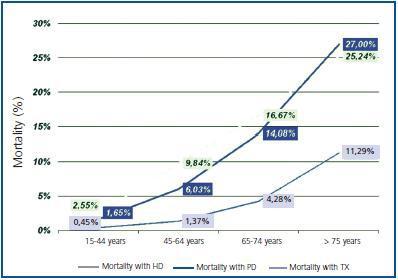

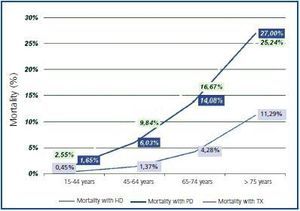

Overall mortality in 2006 was 8.83%. By last recorded treatment method, the mortality rate was 15.52% on HD, 9.83% on PD and 1.73% for TX. The differences in mortality rates remain similar between different treatment methods across all age groups, except in the over 75 group in which rates for HD and PD converge (figure 9). We must be mindful of the fact that mortality is registered for the last treatment method received by a patient.

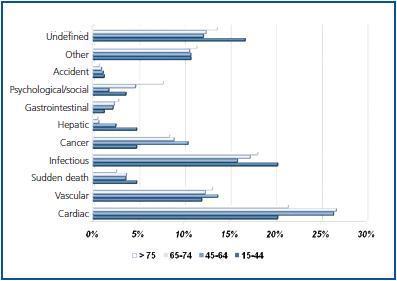

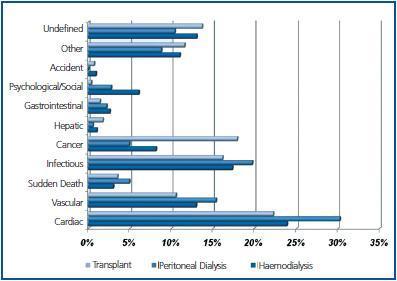

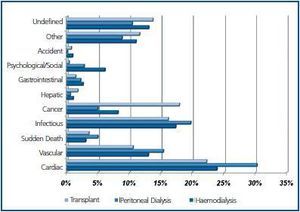

The most frequent causes of death for all treatment methods and age groups are cardiovascular diseases, which account for 37% of the total mortality, followed by infectious diseases (17%) and neoplasias; these last are the second-highest cause of death in transplant patients, reaching 18% in this group (figures 10 and 11).

COMPARISON WITH INTERNATIONAL REGISTRIES

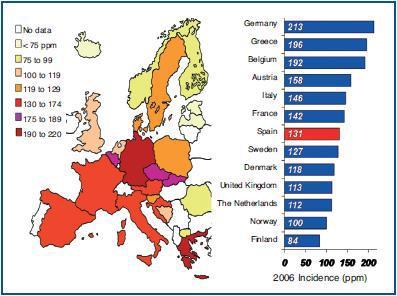

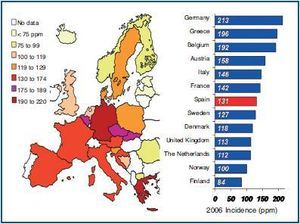

When Spain¿s overall data are compared with data in the European registry ERA-EDTA,3 we see that in 2006, Spain¿s average incidence rate was below that of Germany (213 ppm), Greece, Belgium, Austria, Italy and France, and higher than that of Scandinavian countries and the United Kingdom (figure 12).

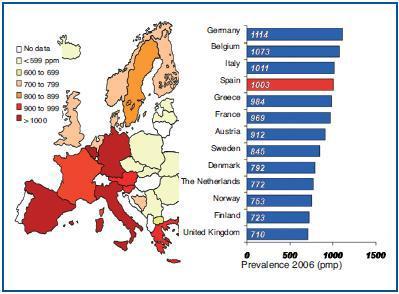

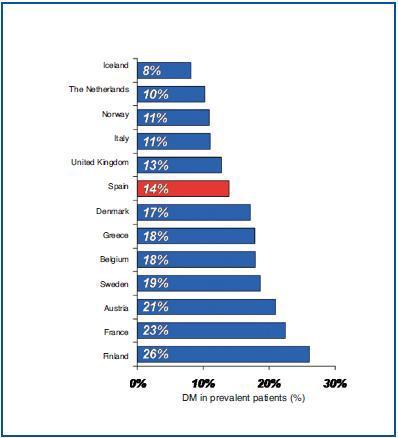

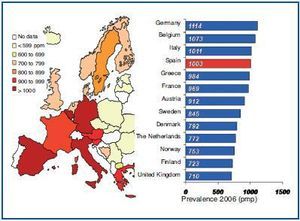

With regard to prevalence, Spain held a medium-high position for 2006, below Germany (1,114.2 ppm), Belgium (1,073 ppm) and Italy (1,011 ppm) and above the United Kingdom, the Scandinavian countries, Austria, France and Greece (figure 13). Spain¿s distribution of PKD causes is similar to that of other neighbouring countries; diabetes mellitus falls into the low-middle range at 14% (figure 14).

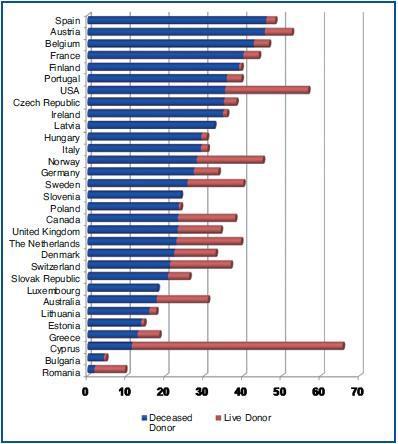

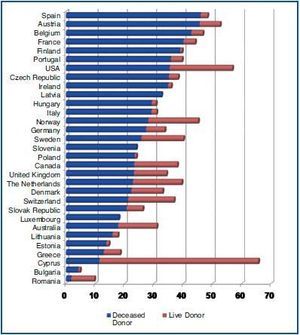

In 2006, Spain held the highest position worldwide for most kidney transplants performed with a deceased donor (46 ppm), and was fourth worldwide for total kidney transplants (48.3 ppm), after Cyprus (65.7 ppm, with a population of 700,000 inhabitants), the United States (56.8 ppm) and Austria (52.6 ppm) (figure 15).14

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In 2006, the registry managed to include 96.1% of the existing Spanish population as of 1 January of that year, and is only lacking data from one Autonomous Community. At 131 ppm, the incidence rate is consistent with the rates between 126 and 132 that were reflected in recent years,1,7,9 and which range widely between different ACs from 103 to 187 ppm. The latter figure is from the Canary Islands, where the number of patients with diabetes mellitus is much higher than in other communities, and is not significantly different from data in previous years.1 Data corresponding to Ceuta and Melilla are skewed due to the fact that patients from the neighbouring country of Morocco receive treatment in both cities, and therefore the reported population cannot be calculated correctly. The percentage of PKD classified as undetermined is still very high among patients beginning treatment (20.5%), while unlike that shown in reports from other international registries,3,5 HBP is not listed as a frequent cause of individual PKD. It seems likely that most of the causes in our records listed as ¿vascular¿ would correspond to some type of nephroangiosclerosis secondary to HBP.

The prevalence has exceeded 1,000 ppm for the first time, although this figure may be overestimated due to the fact that the information provided by some ACs has no validation mechanisms, as it does not come from established registries. For example, the total prevalence in the Madrid Autonomous Community (1,258.5 ppm), which is much higher than that in other ACs (table 2), must be due to overestimation of the number of prevalent patients with a functional TX (770.8 ppm). This number includes most of the patients who have undergone transplants in Madrid hospitals and are still receiving some check-ups in those centres, although they reside in other ACs and also figure in those registries. If we correct the functioning TX figure for the Madrid Autonomous Community by approximating values from other ACs with a similar population and structure, the prevalence should be about 969 ppm. Other prevalence biases tending in the opposite direction, and whose impact on national figures is difficult to define, are to be seen in data from the Balearic Islands. These lack information from the centre which has highest number of patients and is the only renal transplant centre in the Autonomous Community. The number of prevalent patients in Navarre with a functioning TX is also lacking.

Despite possible biases in the prevalence rates, it is obvious that patients with a functioning TX account for about 50% of the KRT patient total. This reflects kidney transplant activity in Spain, which continues to hold the number one position worldwide in kidney transplants from deceased donors, and is one of the world¿s top four countries in total kidney transplant numbers.

The population of KRT patients continues to age, yet overall mortality rates remain below 10%, probably due to the effect caused by transplants. The leading cause of death is cardiovascular disease for patients of all ages and undergoing all treatment methods. The second is infectious disease except for transplant patients, in whom the neoplasia rate is higher.

The increase in reporting, the organisation of new AC registries and AC cooperation with the national registry allow us to receive more complete information which will improve in quality as the new registries are developed. In this way, we may offer information that is relevant and useful for decisionmaking by both the health care administrations and by the nephrology community in general.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

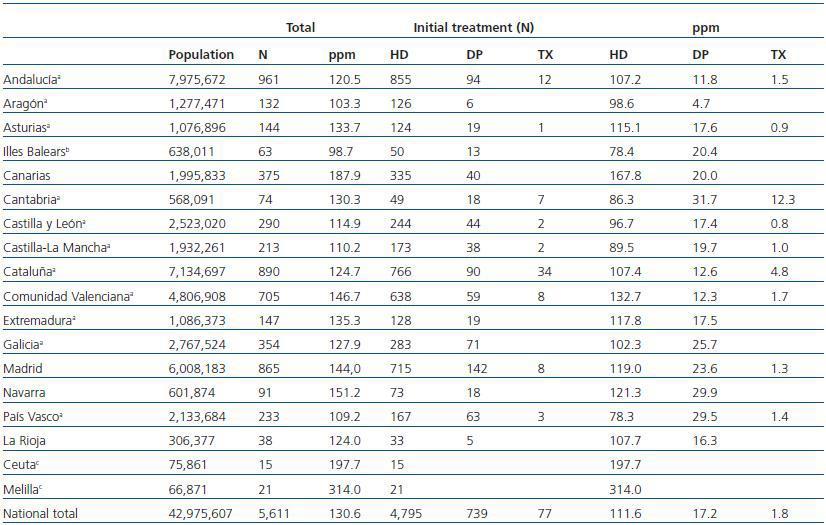

Table 1. 2006 incidence of initial KRT by sex and treatment method

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

Table 2. Prevalence by treatment method on 31 December 2006.

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

Table 3. Kidney transplants performed in Spain in 2006, by Autonomous Community

Figure 8.

Figure 9.

Figure 10.

Figure 11.

Figure 12.

Figure 13.

Figure 14.

Figure 15.