To the Editor,

Secondary amyloidosis (AA) is an uncommon cause of nephrotic syndrome in patients infected by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The cases mentioned until now have been in patients infected by HIV that use parenteral drugs, with amyloidosis appearing as a consequence of chronic inflammation produced by the multiple skin infections related to the use of these drugs. In addition to the cutaneous inflammation caused by the use of parenteral psychotropics, immune disorders are produced that predispose the patient to amyloid deposits due to their reduced degradation in the body. Specifically, an interleukin 2 (IL-2) deficit has been described in one of these disorders. Here we report the case of a patient with an HIV infection that was an old user of intravenous drugs, who developed acute renal failure and complex nephrotic syndrome due to secondary amyloidosis.

The patient, of 51 years, was a consumer of 37 packs of cigarettes/year and occasional user of cocaine and cannabinoids, and until 16 years prior, was an intravenous heroin addict, with HIV infection recognised 25 years prior; received multiple doses of retroviral treatment due to failure and viral resistance issues, and is currently under treatment with maraviroc, raltegravir, darunavir, and norvir, with adequate viral loads and CD4 levels since 1 year prior. An HCV infection was diagnosed in 2006, but treatment was ruled out at that time due to difficulties with compliance. The patient sought treatment for dyspnoea, purulent cough, fever of 40ºC, abdominal distension, and general poor physical state with 10 days evolution. Upon hospitalisation the patient was in a poor general state of health, normotensive, afebrile, with severe bradycardia at 45bpm. The physical examination revealed cutaneous-mucosal pallor, soft tissue oedema, bimalleolar cold, prolonged expiratory interval with diminished respiratory sounds in the apical thirds of both hemithoraxes, crepitation and bilateral rhonchi, distended abdomen with diffuse pain upon deep palpation, timpani to sound, and absence of bowel sounds.

Complementary examinations revealed normocytic/normochromic anaemia at 10.9g/dl, leukocytosis at 11 700x103/µl, with neutrophilia and lymphopoenia (85% and 8%, respectively). We also observed elevated urea and creatinine values (293mg/dl and 9.53mg/dl, respectively), hyperkalemia at 7mEq/l, and hyponatraemia at 125mEq/l, with metabolic acidosis. The urine sediment analysis revealed a red blood cell count of 563 cells/µl, leukocytes at 103 cells/µl, proteins at 351mg/dl, and Fe Na+ was 2.6%. Antigenuria for pneumococcus was positive. We observed heterogeneous opacities with apex air bronchograms in both lung fields in the chest x-ray. The abdominal x-ray showed diffuse colon dilation, with no view of flatulence. An abdominal ultrasound taken as an emergency procedure showed the kidneys at 15cm (nephromegaly) with cortical hyperechogenicity, symmetrical resistive index, and free ascites. The ECG indicated nodal rhythm. We performed a computed tomography of the abdomen, observing oedema of the subcutaneous cellular tissue, bilateral pleural effusion, ascites, and mural thickening of the small intestinal loops, with no evidence of occlusion, subocclusion, or findings indicative of ischaemia. We also observed globular kidneys with significant phase delay and attenuation.

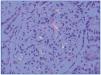

The patient had satisfactory evolution in terms of the respiratory infection (following antimicrobial treatment) and abdominal distension. However, the deteriorated renal function persisted, with glomerular filtration rates close to 18ml/min. The 24-hour urine analysis revealed proteinuria at 22g and persistent microscopic haematuria. The tentative diagnosis of complex nephrotic syndrome led to a renal biopsy, in which we observed a total of 11 glomeruli, with diffuse, global mesangial expansion and a positive Congo red stain for acellular nodes, thickening of the basal capillary membranes, dilated tubules with dense intratubular casts and some inflammatory cells, and interstitial oedema (Figure 1). The permanganate test also resulted positive. The immunohistochemical analysis was positive only for amyloid AA.

We did not identify any neoplastic, infectious, autoimmune, or anti-inflammatory pathologies that could explain the presence of the secondary amyloidosis.

The relationship between the subcutaneous and/or intravenous consumption of drugs, above all heroin, and the development of secondary amyloidosis has been well-known for over 30 years,1-3 mainly in patients that develop repeated cutaneous infections. Until now, only two cases have been recorded in the literature4,5 of patients infected with this virus and with amyloidosis that have no history of drug consumption. Despite the unclear nature of the relationship between amyloidosis and HIV, it has been observed that serum amyloid A protein (SAA) levels are high in these patients,6 which would, in theory, predispose the patient to the development of amyloidosis. The mechanism that could explain the increased secretion of amyloid A is the reduction of IL-2 levels7 due to HIV infection, which would cause a decreased expression of the IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra), which in turn would stimulate tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) and the activation of NFκ−β‚ which stimulates the production of SAA.8

In the case of our patient, given the long evolution of the HIV infection and long history of parenteral drug consumption, it would be impossible to discern the cause of the amyloidosis, which could be due to drug consumption and recurrent infections, the HIV infection, or perhaps the sum of all of these factors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Figure 1. Positive Congo red staining for mesangial deposits