Tumoural calcinosis (TC) is a rare disorder of phosphorus metabolism, characterised by the formation of periarticular deposits of calcium phosphate.1 The disease is the result of a defect in renal phosphorus excretion, due to mutations in the genes for fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), Klotho (KL), and N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-3 (GALNT3). The loss of FGF23 function results in increased tubular phosphorus reabsorption, and subsequent deposition in subcutaneous tisses.2

We present the case of a 23-year-old man with no significant past medical history, whose symptoms began at the age of 18 years, with the appearance of a mass in the right dorsal region, lateral buttock, and thigh. The patient reported a progressive increase in size of the mass, related with physical activity, and pain in the affected limb as a functional limitation. Six months before his admission to our hospital, the tumour had been excised, measuring 18×7cm from the right thigh, and 20×10cm from the right buttock, with amorphous characteristics.

On admission, he had a solid painless mass in the area of excision on the superficial lateral right thigh, measuring 10×4×6cm. Laboratory analysis reported normal serum levels of calcium, phosphate, creatinine, albumin, and PTH. X-ray revealed a multinodular calcified mass around the right hip joint.

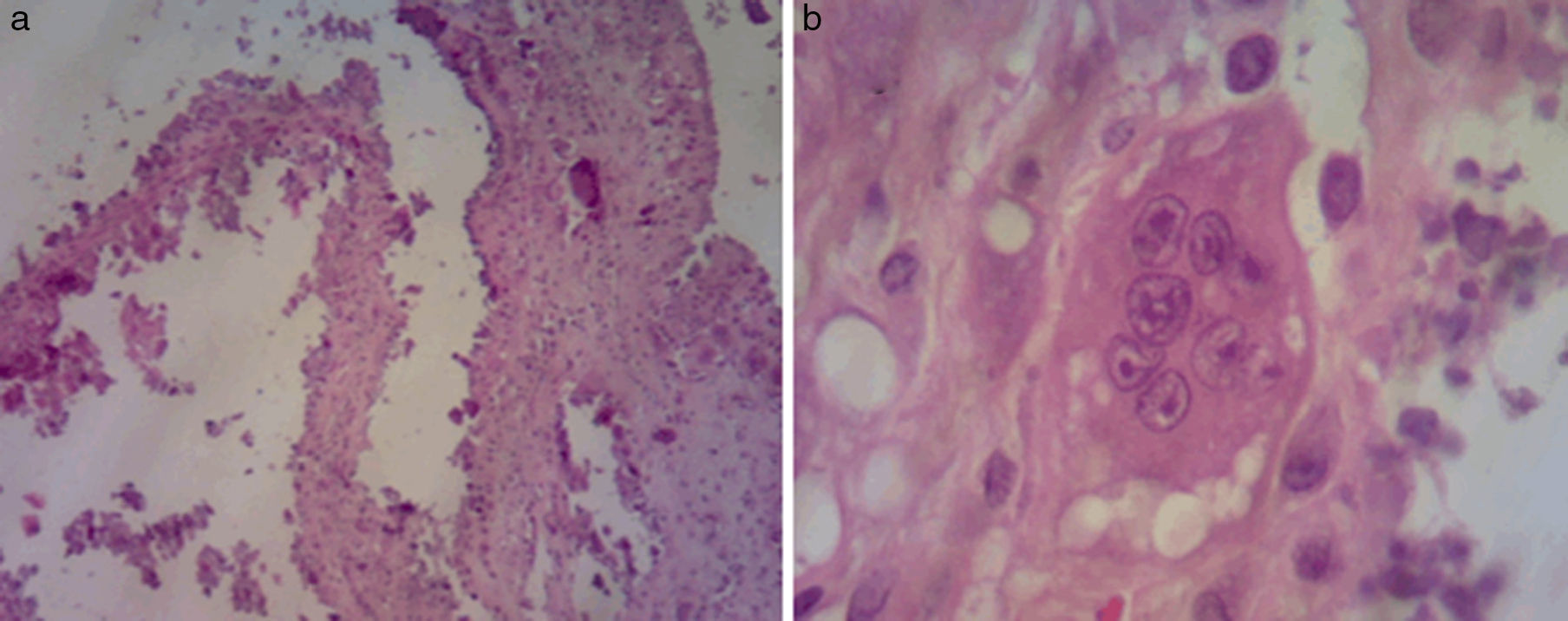

Biopsy of the lesion reported amorphous calcified nodules, some surrounded by a proliferation of macrophages and osteoclast-like giant cells, separated by dense fibrous tissue, consistent with TC (Fig. 1). He was followed up for 2 years while receiving acetazolamide (August 2008 to October 2011) and showed clinical improvement and cessation of growth of the lesions. There were no reported acid–base disturbances during treatment. A follow-up X-ray was taken 7 years after starting treatment, with no increase in the size of the lesions (Fig. 2).

The pathophysiology of TC is based on abnormal phosphorus metabolism.3 Serum phosphate concentration is regulated by endocrine communication between bone, kidney, and the intestine.4 The endocrine factors involved in phosphate metabolism are 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D3, parathyroid hormone (PTH) and FGF23. FGF23 and PTH act synergistically to reduce the expression of the cotransporters NaPi-IIa and NaPi-IIc in the brush border of the proximal renal tubule, increasing renal phosphorus excretion.5

FGF 23 is a glycoprotein, formed by 251 amino acids, and has an N-terminal and a C-terminal made of 71 amino acids.6 It promotes phosphorus excretion by reducing the expression of NaP(i) cotransporters in the proximal tubular cell brush border.3 For FGF23 to bind to its receptor, FGFR1c, Klotho is essential to form a functional heterodimer.7 FGF23 is glycosylated by GALNT3.8 Only the complete FGF23 protein is biologically active. Therefore, an abnormality at any of these points can lead to increased tubular phosphorus reabsorption, which is what happens in TC.3

The disease manifests as hyperphosphatemia and massive calcium deposition in the subcutaneous tissue, which are the main causes of patient symptoms.3 This disease is more frequent in women and in patients of African origin, with initial presentation in childhood or early adolescence.2

The treatment of TC can be divided into surgical excision and medical treatment. Surgical excision of the lesion is a well-documented treatment, but recurrence is common. Furthermore, this patient had shown recurrence after surgical excision, probably due to the tumour being poorly-circumscribed.9 Medical treatment is preferable because of the metabolic nature of the disease. Described treatments include dietary phosphate restriction, antacids, phosphaturic drugs, and phosphate binders. However, the most effective demonstrated treatment is the combination of surgical excision with phosphate restriction and acetazolamide.10

Previous studies have demonstrated positive results with the use of acetazolamide as a phosphaturic treatment for TC, causing mild metabolic acidosis in these patients as an adverse effect. Acetazolamide, a sulphonamide-derivative, acts as a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor in the apical and basolateral membrane of the proximal tubule lumen. It induces natriuresis, kaliuresis, phosphaturia and bicarbonaturia. This causes a reduction in these ions in the body, leading to clinical and biochemical improvement in patients with hyperphosphataemia.10

Our patient improved clinically after starting therapy with acetazolamide, with reduced pain and cessation of tumour formation with no tumour recurrence, as had occurred after the previous surgical excision of the lesion. Phosphorus levels decreased but did not reach normal levels.

Please cite this article as: Landini-Enríquez V, Escamilla MA, Soto-Vega E, Chamizo-Aguilar K. Respuesta a acetazolamida en paciente con calcinosis tumoral. Nefrologia. 2015;35:504–506.