Lanthanum carbonate is a powerful phosphate binder that has shown efficacy and safety in clinical trials for hyperphosphataemia management, although there are few data in regular clinical practice. The study's objective was to evaluate, in regular clinical practice, its efficacy and safety in patients on dialysis. We retrospectively collected data from 15 months of monitoring, corresponding to 3 months prior to the start of treatment with lanthanum carbonate until 12 months after the start. Results included values of serum calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, iPTH, hepatic enzymes and haemogram, as well as the daily-prescribed dose of lanthanum carbonate, the concomitant medication, treatment compliance and adverse events. 647 patients were included of which 522 completed the study. Abandonment, for the most part, was due to gastrointestinal disorders (26%) and hypophosphatemia (19%). Serum phosphorus decreased from 6.4 ± 1.7mg/dl (start) to 4.9 ± 1.4mg/dl (12 months) (P<.001). At the end of the monitoring period, 47% were within the desired phosphorus range (3.5-5mg/dl). There were no significant variations in the remaining parameters. Initial dose of lanthanum carbonate: 1900mg/day; and end dose: 2300mg/day. The variables independently associated with phosphataemia were baseline serum phosphorus and treatment compliance. In relation to safety, we observed 238 slight or moderate adverse effects in 117 patients, with 88% linked to gastrointestinal abnormalities. In conclusion, lanthanum carbonate reduces the serum phosphorus values in patients on dialysis with a good safety profile and acceptable adherence to that profile, with gastrointestinal disorders being the most frequent adverse effect.

El carbonato de lantano es un potente captor de fósforo que en ensayos clínicos ha mostrado eficacia y seguridad para el manejo de la hiperfosforemia, aunque existen pocos datos en la práctica clínica habitual. El objetivo del estudio fue evaluar, en la práctica clínica habitual, su eficacia y seguridad en pacientes en diálisis. Se recogieron, retrospectivamente, datos de 15 meses de seguimiento, correspondientes a los 3 meses previos al inicio del tratamiento con carbonato de lantano y 12 meses después del inicio. Los datos incluían valores séricos de calcio, fósforo, fosfatasa alcalina, PTH, enzimas hepáticas y hemograma, así como la dosis diaria prescrita de carbonato de lantano, la medicación concomitante, el cumplimiento terapéutico y los eventos adversos. Se incluyeron 674 pacientes, de los cuales completaron el estudio 522. Los abandonos se debieron en mayor medida a trastornos gastrointestinales (26 %) e hipofosfatemia (19 %). El fósforo sérico disminuyó de 6,4 ± 1,7 mg/dl (inicio) a 4,9 ± 1,4 mg/dl (12 meses) (p < 0,001). Al final del seguimiento el 47 % se encontraba dentro del rango de fósforo deseado (3,5-5 mg/dl). No hubo variaciones significativas en el resto de los parámetros. Dosis inicial de carbonato de lantano: 1900 mg/día, y dosis final: 2300 mg/día. Las variables que se asociaron de forma independiente con la fosforemia final fueron el fósforo sérico basal y el cumplimiento terapéutico. Respecto a la seguridad, se observaron 238 efectos adversos leves o moderados que ocurrieron en 117 pacientes, estando el 88 % relacionado con alteraciones gastrointestinales. En conclusión, el carbonato de lantano reduce los valores séricos de fósforo en pacientes en diálisis con un buen perfil de seguridad y aceptable adherencia a este, siendo los trastornos gastrointestinales el efecto adverso más frecuente.

The rate of mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD ) is higher than in the general population, mainly due to cardiovascular events. This is due to a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, such as CKD itself, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia and arterial hypertension, and also, significantly, hyperphosphataemia1-3.

KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) guidelines recommend serum phosphorus values between 3.5 and 5 mg/dl4 for patients on dialysis. Current recommendations of the Spanish Society of Nephrology (SEN) are more demanding and suggest serum levels between 3.5 and 4.5mg/dl, although levels up to 5mg/dl5 are considered to be acceptable. The main reason for the strict control of serum phosphorus levels is the fact that there is experimental and clinical evidence regarding the association of hyperphosphataemia with vascular calcification, secondary hyperparathyroidism, and, in particular, with increased morbidity and mortality1-3,6,7.

In spite of dietary phosphorus restriction and improvement in dialysis techniques, a high percentage of patients requires phosphate binders to maintain serum phosphorus within recommended safety margins7. Lanthanum carbonate is a potent phosphate binder available in our country since 2008. It has shown efficacy and safety in controlling hyperphosphataemia in clinical trials8-13, although there is little data regarding its efficacy in routine clinical practice, which is therefore the object of this study.

PATIENTS AND METHOD

The aim of the study was to assess, in normal clinical practice, the efficacy and safety of lanthanum carbonate as a phosphate binder in patients on dialysis. The study was conducted in 49 Spanish hospitals, where we retrospectively collected data from 15 months of monitoring, corresponding to 3 months prior to the start of treatment with lanthanum carbonate until 12 months after the start. Prescription was made at the discretion of the nephrologist in charge of the patient. We included 680 CKD patients on dialysis who started treatment with lanthanum carbonate to control hyperphosphataemia. The latter was defined as serum phosphorus values >5mg/dl. Inclusion criteria were as follows: patients older than 18 years of age who had been treated with lanthanum carbonate for at least one month.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: hospitalisation or recent surgery (less than one month prior to the start of lanthanum carbonate), changes in phosphate binder doses and/or changes in the frequency or dialysis technique in the last three months prior to start of lanthanum carbonate. The study was approved by the ethics committees of the participating hospitals and all patients gave their informed consent.

The study consisted in the collection of retrospective data 3 months before the start of treatment with lanthanum carbonate, at the start of treatment with lanthanum carbonate (baseline), at 15 days from the start, every month for the first 6 months, and then, subsequently, at 9 and 12 months. At each point in time serum values were collected for: calcium, phosphorus, total alkaline phosphatase, parathyroid hormone (PTH), liver enzymes and blood count. Data was also collected on the daily dose of lanthanum carbonate and concomitant medication (active vitamin D, calcimimetics and other phosphate binders) prescribed, treatment compliance and adverse events.

The percentage of adherence was evaluated in accordance to data from the clinical history recorded by the physician. The estimate was based on the pills prescribed versus those the patient had taken, and after determining the degree of compliance with main meals (breakfast, lunch and dinner) the total percentage was calculated. All data were reflected in a manual data collection notebook.

The following variables were analysed: a) reduction of serum phosphorus, b) percentage reduction in serum phosphorus compared to levels prior to treatment with lanthanum carbonate, c) percentage of patients within the normal range of serum phosphorus (3.5-5 mg/dl). The secondary variables were as follows: a) the number and degree of adverse events in the study population attributable to lanthanum carbonate, b) the number and percentage of patients experiencing any adverse event.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software v15 for Windows. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and confidence interval (CI) or median and range (R) (p25 - p75) if the distribution was skewed. Comparisons were performed using the χ2 test for categorical variables or Fisher's test if the distribution was abnormal. Comparisons between continuous variables were performed using Student's t test or ANOVA if there were more than two variables. Medians were compared with non-parametric tests. Analysis was performed per protocol and intention to treat. A value of P<.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

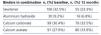

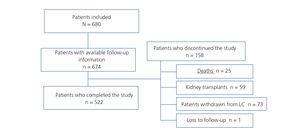

Of the 680 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 6 were excluded from the analysis due to lack of information during follow-up. Of the 674 patients included in the study, 522 completed the study and 152 did not complete the study. The reasons for discontinuation of the study are detailed in Figure 1. Those due to lanthanum carbonate withdrawal were gastrointestinal adverse effects: 26.1%, hypophosphataemia: 19.1%, the patient’s choice, 11%, poor compliance: 9.6%, changes in dialysis technique: 9.6%, hospital admission: 8.2%, parathyroidectomy: 2.8%, and non-specified: 13.7%. Table 1 shows baseline demographic characteristics. The average age of the patients was 59±16,1 years; 60% were males. The mean time on dialysis was 53 months and 36.9% of patients had started dialysis in the past 20 months.

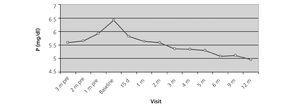

After twelve months of treatment in the protocol based analysis serum phosphorus decreased from 6.4 ± 1.7mg/dl (baseline) to 4.9 ± 1.4mg/dl (end of study), and in the intention to treat analysis, from 6.4 ± 1.7mg/dl to 5,0 ± 1,5 mg/dl (end of study), resulting in a mean decrease of 1,4 mg/dl (95% CI -1.26, -1.56, P<.001) (Figure 2). Significant reduction of 10.6% phosphorus after 15 days of treatment was observed, which reached 20% at 12 months. It was found that 47% (protocol based analysis) and 44.4% (ITT analysis) of patients were within the desired phosphorus range (3.5-5mg/dl ).

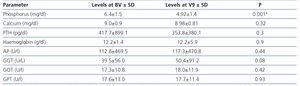

There were no significant changes in other relevant parameters of mineral metabolism such as calcium (Figure 3), total alkaline phosphatase and PTH (Figure 4). There were also no significant changes in serum levels of liver enzymes (GPT, GOT and gamma- GT) or haemoglobin levels (Table 2). The percentage of patients on active vitamin D was 40.8% at baseline and 42% at the end of the study, and those on calcimimetics was 25.6% and 46.3%, respectively.

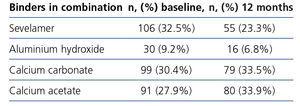

The baseline dose of lanthanum carbonate was 1900mg/day and the final dose 2300mg/day, mean dose throughout the study was 2174mg/day (Table 3). 80% of patients took the drug in divided doses three times a day. The increase in doses of lanthanum carbonate observed from beginning to end of the study was associated with a decreased use of other phosphate binders. At baseline, 66% of patients received lanthanum carbonate in combination with some other phosphate binder, but this percentage dropped to 31.8% at endpoint. The most commonly used combinations of binders at baseline and end of the study are described in Table 4.

No significant differences were seen in the reduction of serum phosphorus in patients receiving lanthanum carbonate as a single drug or combined with other phosphate binders (reduction of 22.2% and 20.7%, respectively). Of the patients who received lanthanum carbonate in combination with some other phosphate binders, 73.7% received only one additional phosphate binder, and the remaining 23.1% received two phosphate binders in addition to lanthanum carbonate (Table 4).

Regarding treatment compliance, it was observed that an average of 82.2% of patients had a compliance >75% with regards to lanthanum carbonate. In this group, serum phosphorus decreased 1.44mg/dl a year after the treatment, whereas this decrease was smaller, 1.26mg/dl, in patients reporting compliance <75%.

At baseline, the relationship between the use of calcimimetics and serum phosphorus was analysed. None of these parameters had statistically significant relevance. Baseline serum phosphorus values were similar in patients who received or did not receive calcimimetics (6.3mg/dl vs. 6.4mg/dl, P=.67). At the end of the study, no statistically significant changes were observed; serum phosphorus levels remained similar (4.8mg/dl vs. 5.1mg/dl, P=.07). Furthermore, no difference in binder doses was seen in patients receiving calcimimetics either at the beginning or end of the study.

Using linear regression, it was seen that variables independently associated with phosphataemia, at 12 months, were baseline serum phosphorus and treatment compliance. An increase of 0.20mg/dl (95% CI 0.13 to 0.28, P<.001) was seen in final serum phosphorus values for each increase of 1mg/dl in serum phosphorus baseline values. In addition, a decrease of 0.02mg/dl in final serum phosphorus (0.03 to 0.01 CI 95%, P<.001) was observed for each 1% increase in treatment compliance.

As regards safety, 238 mild to moderate adverse effects occurred in 117 patients (Table 5), most of them (88%) related to gastrointestinal conditions. There were only two cases of severe intensity and both corresponded to patients with abdominal pain. The causes of death were cardiovascular diseases (15), neoplasia (3), infections (3), respiratory conditions (1) and others (3); there were no cases of treatment-related deaths.

DISCUSSION

The study analysed 674 patients from 49 dialysis centres in Spain during 12 months who received lanthanum carbonate as part of routine clinical practice. It was noted that this phosphate binder, both as monotherapy and in combination with one or more phosphate binders was effective in reducing phosphataemia using an average dose of 2174 mg/day of lanthanum carbonate.

At the end of the study, a significant mean reduction in serum phosphorus of 1.4mg/dl was seen, similar to previously published figures in both clinical trials and follow-up studies7,10-16. Based on desirable values for phosphataemia according to current SEN guidelines during the study (3.5-5mg/dl), 44.4% of patients (ITT analysis) were within the desired range at end of follow-up. However, 55.6% were out of range, confirming once more the difficulty of controlling serum phosphorus levels in dialysis patients. This percentage must be tempered by the fact that 19% of patients had to be excluded from monitoring due to an excessive decrease in serum phosphorus.

An important fact to be noted was that the initial value of serum phosphorus and compliance were the only independent variables that were associated with final serum phosphorus levels. At a higher value of baseline serum phosphorus, there was a corresponding higher final value of serum phosphorus, this is a logical and expected result, not always seen in studies of this type6. Despite the significant reduction in serum phosphorus, no significant changes were observed in serum PTH, a fact which indicates that although experimentally lanthanum chloride has been shown to be capable of activating the calcium sensor and decreasing PTH17 synthesis, lanthanum as lanthanum carbonate has not been associated with decreased PTH or bone remodelling10,18. Nor were there significant changes in total alkaline phosphatase levels.

Long-term studies conducted in haemodialysis patients receiving lanthanum carbonate showed no evidence of toxicity or bone mineralisation abnormalities19; it has even been suggested that lanthanum carbonate can improve bone health18-22. In one of these open and prospective18 studies, the results of bone biopsies showed increased bone turnover after a year’s treatment with lanthanum compared with patients treated with other phosphate binders. In addition, at two years, bone biopsies of patients treated with lanthanum showed greater bone volume compared to the control group. With regards to safety, as has been described in other studies with follow-up greater than six years23,24, in our patients, no liver function abnormalities were seen, including AST, ALT, and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase levels.

The use of lanthanum carbonate helped reduce the need for phosphate binders combined, the percentage of patients with combined therapy was 66% at baseline and decreased to 31.6% at the end of the study. The efficacy of lanthanum carbonate monotherapy and the possibility of reducing the number of phosphate binders can reduce the number of pills patients receive, which facilitates compliance, a factor of significant importance in the management of hyperphosphataemia in patients on dialysis24.

The use of vitamin D remained stable throughout the study, increasing by only 1.2%, while the use of calcimimetics significantly increased (20.7%), almost duplicating the initial rate. It must be remembered that this coincided with the gradual introduction of calcimimetics in our country. Analysing the relationship between PTH and calcimimetics, it was observed that the use of these is associated with a decrease in PTH levels.

As expected, in patients with combined therapy, the dose of lanthanum carbonate was lower than in patients receiving monotherapy. However, this did not increase the adverse effects of lanthanum, which remained at similar rates and even lower than those observed in previous studies with other phosphate binders7,12,24-26 and which were mainly circumscribed to the gastrointestinal tract (Table 4).

Treatment compliance is one of the most important factors to achieve adequate control of serum phosphorus11,27-30. In our study 82.2% of patients reported a compliance of more than 75% of prescribed doses. In a metaanalysis of 34 studies of phosphate binders, treatment non-compliance ranged from 22% to 79% with a mean of 51%31. Therefore, lanthanum carbonate compliance was high and probably one of the study factors responsible for good control of serum phosphorus, underlined by linear regression analysis, indicating that increased compliance was associated positively and significantly with better control of serum phosphorus.

The mean dose of lanthanum carbonate is rather high and 80% of patients took lanthanum carbonate in three daily doses, although the amount of each dose is not known. In Spain, the phosphorus content of breakfast is usually very low and sometimes zero; therefore, a good individual dietary history will probably allow a better fit of phosphate binders based on the phosphorus content of meals as well as a reduction in dose without affecting serum phosphorus levels32.

The fundamental limitations of the study are those of a retrospective analysis, particularly in regard to the assessment of adverse effects and compliance.

In conclusion, lanthanum carbonate as a phosphate binder can quickly and sustainably reduce serum phosphorus in dialysis patients, allowing a reduction in the use of combination therapy. The drug has a good safety profile and acceptable compliance, gastrointestinal disorders being the most common side effect.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Cristina Fernández carried out the statistical analysis.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Table 1. Demographic and baseline characteristics of the study population

Table 2. Laboratory parameters at baseline and after 12 months of treatment.

Table 3. Mean dose of Lanthanum carbonate used during the study.

Table 4. Combination of binders at baseline and at end of study visits.

Table 5. Number of adverse events.

Figure 1. Inclusion and follow-up of study patients.

Figure 2. Evolution of serum phosphorus during the 3 months prior to starting treatment with Lanthanum carbonate and during the 12 months of treatment.

Figure 3. Evolution of serum calcium during the 3 months prior to starting treatment with Lanthanum carbonate and during the 12 months of treatment.

Figure 4. Evolution of parathyroid hormone serum levels throughout follow-up.