To the Editor,

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is a hereditary disease caused by mutations in genes PKD1 and PKD2, which codify polycystins 1 and 21. The disease usually progresses more quickly in patients with PKD1 involvement, although there is wide interindividual variability, even within the same family. Furthermore, the progression of a given patient is not linear and may occasionally accelerate. Explanations for this phenotypic variability include the existence of mutations of varying severity, the individual’s genetic load, the need for a second genetic hit and the impact of environmental factors or a third hit2. From the second hit hypothesis, it is deduced that polycystic kidney disease is phenotypically dominant but molecularly recessive, such that, for a tubular cell to create a cyst, a second somatic mutation in the second pkd1 or pkd2 gene would be necessary, as well as the inherited genetic mutation. With respect to the third hit, there is evidence in animal models that inflammation may contribute to the progression of cystogenesis. Tumour necrosis factor (TNF), the quintessential proinflammatory cytokine, decreases the expression of polycystin 2 in mice3,4. We reported the evolution of kidney function and volume in a patient with ADPKD treated for more than one year with TNF-neutralising antibodies due to another disease.

CASE REPORT

A 35-year-old male diagnosed with HLA B27-positive ankylosing spondylitis in 2011. An abdominal ultrasound displayed multiple hepatic and renal cysts. The right kidney was 18cm and the left kidney was 19cm. Given the lack of a family history of cystic diseases, he was diagnosed with polycystic kidney disease due to de novo mutation.

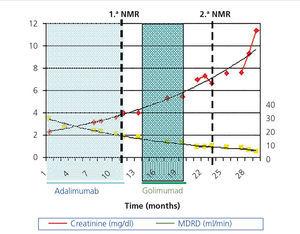

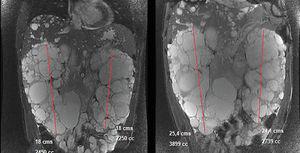

In March 2011, he began treatment with 40mg adalimumab (Humira®) every 15 days. At that time he had: haemoglobin (Hb) 12.4g/dl, creatinine (Cr) 2.3mg/dl, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (according to Modification of Diet in Renal Disease) 34ml/min/1.73m2, proteinuria 10mg/dl. In September 2011 he had: Cr 3.24mg/dl, eGFR MDRD 23ml/min/1.73m2, proteinuria 1.78g/24h (Figure 1). Treatment was discontinued in January 2012 because the patient developed polyneuropathy and purpura. In February 2012 a nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) displayed a right kidney of 18cm (volume of 2450ml) and a left kidney of 18cm (2250ml). In April 2012 the patient began a course of 50mg Golimumab (Simponi®) every five weeks. Six doses were administered and it was discontinued in September 2012 when the patient complained of a notable increase in his abdominal diameter and an umbilical hernia, which was directly related to the administration of the drug. A final dose was administered in December 2012. In March 2013, another NMR displayed a right kidney of 25.4cm with a volume of 3899ml and a left kidney of 24.1cm with a volume of 2739ml (Figure 2) and a slight increase in a much smaller amount of hepatic cysts.

DISCUSSION

There is no specific treatment for ADPKD. However, various therapeutic approaches designed based on findings in experimental models and clinical observations are being studied. The TEMPO 3:4 trial observed that tolvaptan reduced the growth rate of cysts and the loss of glomerular filtration5. It had previously been observed that vaptans slowed down the progression of murine cystogenesis6. In clinical trials the mTOR (mammalian Target of Rapamycin) inhibitor sirolimus did not stop the growth of renal cysts and everolimus decreased the growth rate, but not kidney function impairment7,8. Again the rationale came from preclinical studies in animals9. The ALADIN trial demonstrated that long-lasting somatostatin slowed down cyst growth10. The choice of somatostatin was based on a case report. A woman with ADPKD received treatment with somatostatin for a pituitary adenoma and her cystic nephropathy improved11. In this regard, observations in a single patient may provide guidance on the potential usefulness of a therapeutic action. In pkd2 +/- mice, TNF increased cystogenesis and etanercept reduced it3. TNF reduced functioning polycystin 2 below a critical threshold as a result of the increased expression of protein FIP-23. Therefore the evolution of the patient whose case we reported during treatment with anti-TNF for a concomitant disease is particularly interesting. During this period, ADPKD progressed rapidly. The eGFR decreased with a slope of -1.1ml/min/month homogenously over time (and the volume of the kidneys increased by a mean of 71% [1938ml]. This progression speed is much higher than that of patients treated with a placebo in recent clinical trials (Table 1)5,7,8,10,12. Contrary to experimental observation3 and the hope placed in the potential efficacy of anti-TNF therapies4, there was no evidence of a therapeutic effect, at least at this stage of the disease. Since this was only one clinical case, it is not a definitive observation. In fact, it may be argued that the existence of a systemic inflammatory disease could have contributed to accelerating the disease. Nevertheless, anti-TNF treatment was effective in controlling the activity of ankylosing spondylitis.

In conclusion, we reported the case of a patient with ADPKD treated with anti-TNF therapy due to a concomitant rheumatic disease, whose kidney disease progressed quickly. This case report argues against the efficacy of anti-TNF therapies for treating the human form of ADPKD.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

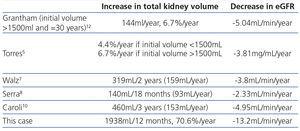

Table 1. Increased kidney volume in patients assigned to the placebo group in large observational studies and clinical trials and in the patient reported

Figure 1. Evolution of renal function over 29 months.

Figure 2. Image comparing kidney size in the nuclear magnetic resonances of 2012 (left) and 2013 (right).