Few studies have investigated the role psychological inflexibility (PI) could have in the context of chronic renal failure. The primary objective of this study was to analyse the psychometric features, the reliability and the validity of the Spanish version of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II) adapted to the context of patients undergoing haemodialysis (HD). The secondary objective was to assess the relationship between PI and parameters related to the adherence to treatment and quality of life in these types of patients.

Materials and methodsProspective cross-sectional study with patients on haemodialysis (N=186).

ResultsThe fat tissue index (15.56±5.72 vs. 18.99±8.91, P=0.033), phosphorus levels (3.92±1.24 vs. 4.66±1.38; P=0.001) and interdialytic weight gain (1.56±0.69 vs. 1.89±0.93, P=0.016) were higher in patients with a higher PI score. Phosphorus levels (P=0.013) significantly explained the variability of PI levels. PI was also shown as a significant predictor (P=0.026) of the variability of phosphorus levels.

ConclusionsThe adaptation of the AAQ-II questionnaire to the HD context led to a valid and reliable measurement of PI in these types of patients and our results also seem to support the relationship between PI and health and quality of life parameters in patients with chronic conditions.

Apenas existen estudios que hayan investigado el papel que la inflexibilidad psicológica (IP) pudiera tener en el contexto de la IRC. El objetivo primario de este estudio fue analizar las propiedades psicométricas, la fiabilidad y la validez de la versión española del Acceptance and Action Questionnaire – II (AAQ-II) adaptada al contexto de pacientes en tratamiento de hemodiálisis (HD). El objetivo secundario fue analizar la relación entre IP y parámetros relacionados con la adhesión al tratamiento y calidad de vida en este tipo de pacientes.

Materiales y métodosEstudio transversal prospectivo con pacientes en hemodiálisis (N=186).

ResultadosEl índice de tejido graso (15,56±5,72 vs. 18,99±8,91; p=0,033), los niveles de fósforo (3,92±1,24 vs. 4,66±1,38; p=0,001) y la ganancia de peso interdiálisis (1,56±0,69 vs. 1,89±0,93; p=0,016) fueron mayores en los pacientes con más puntuación en IP. Los niveles de fósforo (p=0,013) explicaron de forma significativa la variabilidad de los niveles de IP, la cual también se mostró como un predictor significativo (p=0,026) de la variabilidad de los niveles de fósforo.

ConclusionesLa adaptación del cuestionario AAQ-II al contexto de HD da lugar a una medida válida y fiable de la IP para este tipo de pacientes y los resultados de este estudio parecen apoyar el papel de la IP con relación a parámetros de salud y calidad de vida en el ámbito de las patologías crónicas.

Psychological inflexibility (PI) is the central concept of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), and is defined as "a rigid pattern of behaviour in which the person lets their actions be guided by fleeting internal experiences instead of freely chosen values".1 In other words, it is a process of behaviour regulation, consisting of avoiding and/or escaping unwanted internal events (thoughts, memories, feelings, sensations, etc.), even when doing so means behaving in a way which is incompatible with one's own values and goals. In contrast, psychological flexibility refers to one's ability to focus on the present moment and, based on what the situation affords, to change or persist with behaviour in the search for goals and values.2,3

There is a great deal of empirical evidence to support the maladaptive role of PI.3 First of all, a strong correlation has been demonstrated between PI and a wide range of psychological symptoms, particularly anxiety, depression, stress and somatic complaints in the field of healthcare.4–7 Secondly, there is a strong negative correlation with measurements of general health and quality of life.8,9 PI is also a factor mediating the effects of a wide variety of psychological constructs and psychological symptoms.10 Lastly, it adds a greater predictive validity for psychological symptoms than other existing constructs.11 PI is, moreover, the key process within ACT, which we propose is of greater utility in the approach to chronic diseases than other psychotherapeutic models.12,13

The instrument most used to assess PI is the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ). Both the first version14 and the second, which resulted in an instrument with greater validity and reliability,15 are validated in Spanish. The psychological intervention model to which this instrument belongs suggests that the concept of PI may vary across different contexts.16 As a result, a multitude of versions of the AAQ have been adapted to different scenarios, both work-related17 and in health. For example, there are versions of the AAQ specifically adapted to chronic diseases such as: chronic pain,18 diabetes,19 cancer,20 obesity,21 epilepsy,22 etc. These studies have described significant relationships between PI and the worsening of symptoms, quality of life and adherence to treatment.

Various studies have investigated the role of acceptance (a process related to the concept of PI) as a strategy to cope with the disease in patients with chronic renal failure.23–25 However, to our knowledge, we are the first to study the concept of acceptance proposed by the ACT model, which is understood as an experiential domain sub-dimension (not as a coping strategy), the function of which is to promote the psychological flexibility of the individual to enable him to focus on his personal values. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to analyse the psychometric properties, reliability and validity of the Spanish version of the AAQ-II adapted to patients on haemodialysis (HD). The secondary objective was to analyse the relationship between the PI variable and the parameters related to adherence to treatment and quality of life in this type of patient.

Material and methodsParticipantsWe conducted a prospective, cross-sectional study with outpatients in the HD programme at the Fresenius Medical Care clinics in the province of Cordoba (San Rafael, Pintor García Guijo, Cabra and Palma del Río), Spain. From the potential sample from the four clinics (n=316), we selected patients (n=186) who met the inclusion criteria: 1) ability to understand and speak Spanish; 2) aged 18–90; 3) have provided a signed informed consent form for the study; 4) more than six months on HD; and 5) not suffer from cognitive impairment or a serious mental disorder. A total of 130 patients were therefore excluded, which resulted in a 58% response rate to the study. After that, we requested authorisation from the Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía Independent Ethics Committee (IEC), which we received in June 2017.

Measuring instrumentsThe following instruments were applied:

- •

COOP-WONCA quality of life charts using the Arenas et al version.26 This is a general questionnaire for assessing health-related quality of life consisting of nine items that rate the following dimensions: 1) physical fitness; 2) feelings; 3) daily activities; 4) social activities; 5) changes in health; 6) overall health; 7) pain; 8) social support; and 9) general quality of life. Each of the dimensions refers to what happened in the last two weeks and is answered with a Likert scale that scores from 1 to 5, with the highest scores reflecting the worst perceived health. In the end, an overall score is obtained corresponding to the sum of all dimensions, except for item 5 which, having a bipolar structure, has a different reading from the rest of the dimensions.27 For the present study it showed a good Cronbach's Alpha (0.77).

- •

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-ii for patients on haemodialysis (AAQHD-II) This instrument (Appendix Table) assesses the level of PI in the context of certain thoughts (items 2 and 3), fears (item 6), treatment regimens (items 4 and 5), situations related to the HD therapy (item 1) and how the treatment regimens affect the patient's life (item 7). It is a seven-item questionnaire with a five-point Likert scale (1= never true, 2= very seldom true, 3= sometimes true, 4= frequently true, 5= always true). The instrument showed a good Cronbach's Alpha (0.72), grouping the items into one single factor, just like the original questionnaire.

- •

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Spanish version by Terol et al.28 This instrument assesses the emotional responses of anxiety and depression in patients with physical and mental disorders and in general population without taking into account somatic symptoms, so limiting the chance of the symptoms of the disease contributing to the scores.29,30 It contains 14 items with a four-point Likert response format ranging from 0 to 3: the higher the score the worse the anxiety or depression. It is made up of two sub-scales: one for anxiety and the other for depression. In this study, a good Cronbach's Alpha (0.83) was obtained, both for the anxiety and the depression sub-scales.

Sociodemographic variables included the dialysis centre, gender, age, marital status, educational level and employment status. Clinical variables included active prescription of psychiatric drugs, time on HD, transplant waiting list, Charlson comorbidity index score, presence of diabetes and type of vascular access. In addition, the average dialysis dose for the month was estimated, measured as Kt/V calculated using the On-line Clearance Monitor (Fresenius Medical Care), Kt On-line Clearance Monitor or eKt/V, the mean pre-HD systolic blood pressure for the month and interdialysis weight gain. We also collected the lab analysis results for that month for potassium, sodium, haemoglobin, transferrin saturation, C-reactive protein, albumin, phosphorus (P) and calcium. Finally, we measured the patients' relative hydration status by bioimpedance spectroscopy and their body composition using the BCM® device (Body Composition Monitor; Fresenius Medical Care), recording the relative overhydration, lean tissue mass, adipose tissue mass, fat tissue mass, lean tissue index, fat tissue index, relative lean tissue mass and relative fat tissue mass. The information for the clinical variables was obtained from the Euclid database31 belonging to Fresenius Medical Care. The data were collected in June and July 2017.

ProcedureThe AAQHD-II was created after a review of items in the Spanish version of the AAQ-II15 and other versions of said instrument used for the study of diabetes,19 cancer20 and obesity.21 The whole AAQHD-II development process was reviewed and agreed on by an interdisciplinary team (nephrologist, psychologist, social worker and nurse) with extensive experience in the treatment of patients on HD. A battery of ten items was then put together and reviewed by another psychologist, author of the Spanish version of the AAQ-II. That battery was administered to a group of six patients on HD to assess their degree of understanding of the items. After evaluating the patients' opinions on completing the questionnaire, three items which seemed ambiguous were removed, while the term "HD" was replaced by the word "dialysis", as the patients are more familiar with that. By consensus from the start, the specialists involved in adapting the questionnaire considered the use of a five-point Likert scale, rather than the seven points in the original scale, to make it easier to understand the response format in view of the advanced age of the target patients.

The evaluation protocol was carried out in the treatment rooms during the patients' haemodialysis sessions by three assessors previously trained in completing the questionnaires. The aims of the study were explained to the patients prior to the questionnaire evaluation, and the questionnaires along with the study instructions were administered to those who agreed to take part by signing the informed consent form. Completion time ranged from 20 to 30min.

Statistical analysisCronbach's alpha and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated to analyse the internal consistency of the AAQHD-II. The item-total correlations were calculated to identify items that should be removed due to a low discrimination index (values below 0.20). The suitability of the data for a factor analysis was measured with the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test. After that, an exploratory factor analysis was carried out using the robust unweighted least squares extraction method using polychroric correlations with the program Factor 10.8.03.32 The number of dimensions was determined by means of a parallel analysis based on the Minimum Rank Factor Analysis.33

In order to verify the convergent validity of the instrument, Pearson's correlations were made between PI and the psychological symptoms (anxiety and depression), and health-related quality of life dimensions.

The data are presented as mean±standard deviation for continuous variables with normal distribution, median and interquartile range (25th percentile-75th percentile) for non-normal continuous variables or percentages for categorical variables.

Those who scored more than 20 points on the AAQHD-II test were defined as "inflexible" patients. This value was chosen because it is a standard deviation above the mean of the AAQHD-II variable, and also for being the cut-off value of the upper quartile of the distribution.

To verify the possible existence of significant differences between the flexible and inflexible patients for the different variables recorded in the study, the Chi-square statistical tests were applied for the categorical variables, Student's t for the normal continuous variables and the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous non-normal variables.

To identify variables associated with PI, a multiple linear regression analysis was performed in which clinical or psychological variables that were significant in the bivariate analysis were included as independent variables.

All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical package SPSS version 23.0. The level of statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

ResultsCharacteristics of the study participantsThe characteristics of the sample used are detailed in Table 1. A total of 186 patients were assessed, 113 (60.8%) male and 73 (39.25%) female. The mean age was 70.17±1.01 years, 97.85% were pensioners or retired, 33.87% had diabetes and the Charlson comorbidity index was 4.

Sociodemographic, quality of life, psychological and medical characteristics of the patients (n=186).

| [17,0]Sociodemographic | [3,0]Clinical | 1 | 44.09% |

| 2 | 21.51% | ||

| 3 | 26.88% | ||

| 4 | 7.53% | ||

| Gender | % Female | 39.25% | |

| Age | Years | 70.17±1.01 | |

| 4,0Marital status | Single | 12.37% | |

| Married | 61.83% | ||

| Cohabiting partner | 2.69% | ||

| Separated/divorced | 4.30% | ||

| Widowed | 18.82% | ||

| [3,0]Educational level | No schooling | 51.08% | |

| Primary | 31.18% | ||

| Secondary | 11.29% | ||

| University | 6.45% | ||

| [2,0]Employment status | No data | 0.54% | |

| Unemployment | 1.61% | ||

| Pensioner/retired | 97.85% | ||

| Quality of life | Health-related quality of life | 21.41±0.39 | |

| [2,0]Psychological | Psychological inflexibility | 15 (11−19) | |

| Anxiety | 5 (2.75−8) | ||

| Depression | 5 (3−8) | ||

| [270]Medical | On psychiatric drugs | Yes | 34.41% |

| Time on haemodialysis (months) | 53 (26.75−104) | ||

| Renal transplant waiting list | Yes | 10.75% | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score | 4 (2−5) | ||

| Diabetic | Yes | 33.87% | |

| Vascular access | (Catheter) | 20.43% | |

| OCM Kt/V | 1.91±0.03 | ||

| OCM Kt | 57.91±0.72 | ||

| eKt/V | 1.7±0.04 | ||

| K (mmol/l) | 5.2±0.06 | ||

| Na (mmol/l) | 139.12±0.2 | ||

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | 11.33±0.1 | ||

| Transferrin saturation (%) | 21 (16−28) | ||

| C-reactive protein (mg/l) | 7.2 (2.8−15.83) | ||

| Pre-HD relative overhydration (%) | 11.4 (5.7−16.7) | ||

| pre-SBP (mmHg) | 133.2±1.73 | ||

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.67±0.02 | ||

| Lean tissue mass (kg) | 30.47±0.72 | ||

| Adipose tissue mass (kg) | 42.74±1.31 | ||

| Fat tissue mass (kg) | 31.41±0.95 | ||

| Lean tissue index (kg/m2) | 11.41±0.22 | ||

| Fat tissue index (kg/m2) | 16.25±0.49 | ||

| Relative lean tissue mass (%) | 41.35±0.92 | ||

| Relative fat tissue mass (%) | 40.45±0.72 | ||

| Total Ca present month (mg/dl) | 8.84±0.05 | ||

| P (mg/dl) | 4.07±0.1 | ||

| HbA1c (last 3 months) (%) | 6.57±0.14 | ||

| Inter-HD weight gain (kg) | 1.62±0.75 |

HD: haemodialysis; pre-SBP: pre-dialysis systolic blood pressure.

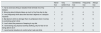

Table 2 shows a comparison of patient scores based on a high or low PI score. Among the sociodemographic variables we found a significant association between PI and gender (P=0.005). In terms of health-related quality of life, the most inflexible patients obtained the worst scores (24.67±5.91; P<0.000). In the emotional symptoms, the most inflexible patients had the highest scores for both anxiety (P<0.000) and depression (P<0.000). Among the medical variables, the most inflexible patients were more likely to be taking psychoactive drugs (P=0.034). The fat tissue index (18.99±8.91; P=0.033), phosphorus levels (4.66±1.38; P=0.001) and interdialytic weight gain (1.89±0.93; P=0.016) were also increased in patients with a higher PI score.

Sociodemographic, quality of life, psychological and medical characteristics according to the degree of psychological inflexibility.

| AAQHD-II | Flexible | Inflexible | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <20 | ≥20 | ||||

| N | 147 | 39 | |||

| [13,0]Sociodemographic | Gender | % Female | 34.01% | 58.97% | 0.005 |

| Age | Years | 70.87±14.16 | 67.51±12.33 | 0.179 | |

| Marital status | Single | 13.61% | 7.69% | 0.279 | |

| Married | 62.59% | 58.97% | |||

| Cohabiting partner | 2.72% | 2.56% | |||

| Separated/divorced | 2.72% | 10.26% | |||

| Widowed | 18.37% | 20.51% | |||

| Educational level | No schooling | 51.02% | 51.28% | 0.263 | |

| Primary | 30.61% | 33.33% | |||

| Secondary | 10.20% | 15.38% | |||

| University | 8.16% | 0.00% | |||

| Employment status | No data | 0.68% | 0.00% | 0.581 | |

| Unemployed | 2.04% | 0.00% | |||

| Pensioner/retired | 97.28% | 100.00% | |||

| Quality of life | Health-related quality of life | 20.54±4.89 | 24.67±5.91 | 0.000 | |

| [1,0]Psychological | Anxiety | 4 (2−7) | 8 (5−13) | 0.000 | |

| Depression | 4 (3−7) | 8 (6−10) | 0.000 | ||

| [27,0]Medical | On psychiatric drugs | Yes | 30.61% | 48.72% | 0.034 |

| Time on haemodialysis (months) | 53 (23−104) | 53 (32−94) | 0.991 | ||

| Renal transplant waiting list | Yes | 10.88% | 10.26% | 0.910 | |

| CCI | 4 (2−5) | 4 (3−5) | 0.243 | ||

| Diabetic | Yes | 30.61% | 46.15% | 0.068 | |

| Vascular access | (catheter) | 19.05% | 25.64% | 0.364 | |

| OCM Kt/V | 1.92±0.42 | 1.85±0.37 | 0.297 | ||

| OCM Kt | 57.38±9.09 | 59.86±11.97 | 0.161 | ||

| eKt/V | 1.68±0.31 | 1.77±0.42 | 0.288 | ||

| K (mmol/l) | 5.21±0.84 | 5.18±0.74 | 0.863 | ||

| Na (mmol/l) | 139.32±2.73 | 138.38±2.58 | 0.056 | ||

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | 11.33±1.38 | 11.35±1.2 | 0.954 | ||

| Transferrin saturation (%) | 22 (16−28) | 21 (16−29) | 0.738 | ||

| C-reactive protein (mg/l) | 6.9 (2.1−17.1) | 8.2 (4.4−14.9) | 0.376 | ||

| Pre-dialysis relative overhydrat. (%) | 11.7 (6.4−16.7) | 9.2 (3.05−15.38) | 0.112 | ||

| pre-SBP (mmHg) | 131.82±22.56 | 138.41±26.91 | 0.122 | ||

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.68±0.32 | 3.63±0.29 | 0.313 | ||

| Lean tissue mass (kg) | 30.11±8.42 | 31.94±13.5 | 0.309 | ||

| Adipose tissue mass (kg) | 41.17±15.52 | 48.97±22.92 | 0.060 | ||

| Fat tissue mass (kg) | 30.26±11.4 | 35.99±16.85 | 0.060 | ||

| Lean tissue index (kg/m2) | 11.22±2.45 | 12.17±4.43 | 0.223 | ||

| Fat tissue index (kg/m2) | 15.56±5.72 | 18.99±8.91 | 0.033 | ||

| Relative lean tissue mass (%) | 41.61±11.62 | 40.3±14.99 | 0.570 | ||

| Relative fat tissue mass (%) | 40.07±9.05 | 41.97±11.6 | 0.364 | ||

| Total Ca present month (mg/dl) | 8.86±0.66 | 8.77±0.63 | 0.491 | ||

| P (mg/dl) | 3.92±1.24 | 4.66±1.38 | 0.001 | ||

| HbA1c (last 3 months) (%) | 6.52±0.95 | 6.71±1.29 | 0.524 | ||

| Inter-HD weight gain (kg) | 1.56±0.69 | 1.89±0.93 | 0.016 |

HD: haemodialysis; pre-SBP: pre-dialysis systolic blood pressure.

As already mentioned in the section on instruments, the AAQHD-II showed acceptable internal consistency in this study. Table 3 shows the content of the items and corrected item-total correlations. The corrected item-total correlations varied from 0.28 (item 4) to 0.61 (item 3). As all scores were greater than 0.20, no items were eliminated because of a low level of discrimination.

Analysis of AAQHD-II item-rest correlation.

| Item | Corrected item-total correlation | Factor loadings |

|---|---|---|

| Item 1. I try to avoid any thing or situation that reminds me of my dialysis | 0.47 | 0.70 |

| Item 2. My concerns about dialysis take up much of my time day to day. | 0.57 | 0.76 |

| Item 3. I very often think I depend on a dialysis machine | 0.61 | 0.81 |

| Item 4. My desire to drink is stronger than my willpower when it comes to controlling what I drink | 0.28 | 0.35 |

| Item 5. I can't stand the pressure of following my diet | 0.37 | 0.47 |

| Item 6. I avoid doing any physical activity (walking, etc) for fear of not being able to do it | 0.42 | 0.58 |

| Item 7. I avoid social situations to control what I eat and drink | 0.34 | 0.40 |

The results showed that the data were appropriate for performing an exploratory factor analysis in view of the fact that Bartlett's test was statistically significant (290.8 [21], P<0.001) and the results of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test were acceptable (0.71). The parallel analysis recommended extracting a single factor that explained 44.31% of the variance (self-value of 3.10). The factor loadings of the items varied from 0.35 (item 4) to 0.81 (item 3) (Table 3)

Evidence of convergent validityTable 4 shows the correlations between the AAQHD-II and the other instruments. The total AAQHD-II score was significantly correlated with both the anxiety (r=0.54, P=0.000) and the depression (r=0.51, P=0.000) sub-dimensions, assessed by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and with the total score for health-related quality of life (r=0.45, P=0.000), assessed with the COOP-WONCA charts, and the following sub-dimensions: social activity (r=0.42, P=0.000), daily activities (r=0.40, P=0.000), feelings (r=0.36, P=0.000), overall health (0.32, P=0.000), quality of life in general (r=0.31, P=0.000), physical fitness (r=0.23, P=0.001) and change in health (r=0.14, P=0.004).

Relationship between AAQHD-II scores, psychological symptoms and quality of life dimensions.

| Variable | r | P |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 0.54 | 0.000 |

| Depression | 0.51 | 0.000 |

| Health-related quality of life (total COOP/WONCA charts) | 0.45 | 0.000 |

| Social activity | 0.42 | 0.000 |

| Daily activities | 0.40 | 0.000 |

| Feelings | 0.36 | 0.000 |

| Overall health | 0.32 | 0.000 |

| General quality of life | 0.31 | 0.000 |

| Physical fitness | 0.23 | 0.001 |

| Change in health | 0.14 | 0.004 |

The results of the multivariate regression analysis are presented (Table 5) with the variables that showed statistical significance in the prediction of PI in the univariate analysis. This analysis shows how the variables being female, health-related quality of life, anxiety, depression, time on HD, albumin, fat tissue index, calcium levels, phosphorus levels and inter-HD weight gain explain a large portion of the PI (R2=46%, P=0.000). However, the only ones to show statistical significance were: anxiety (P=0.000), depression (P=0.009) and phosphorus levels (P=0.013).

Multivariate linear regression to identify predictors of psychological inflexibility.

| B | Std. Error | P coefficients | P model | R2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 15.369 | 5.121 | 0.003 | [10,0]0.000 | [10,0]0.469 | ||

| Sociodemographic | Gender | Female | –1.235 | 0.720 | 0.088 | ||

| Quality of life | [0,2–3]Health-related quality of life | 0.146 | 0.083 | 0.081 | |||

| [1,0]Psychological | [0,2–3]Anxiety | 0.481 | 0.098 | 0.000 | |||

| [0,2–3]Depression | 0.317 | 0.120 | 0.009 | ||||

| [5,0]Medical | Time on haemodialysis (months) | –0.008 | 0.005 | 0.086 | |||

| Albumin (g/dl) | –0.578 | 1.094 | 0.598 | ||||

| Fat tissue index (kg/m2) | 0.033 | 0.052 | 0.524 | ||||

| Total Ca present month (mg/dl) | –0.905 | 0.533 | 0.091 | ||||

| P (mg/dl) | 0.608 | 0.243 | 0.013 | ||||

| Inter-HD weight gain (kg) | 0.503 | 0.483 | 0.299 | ||||

HD: haemodialysis.

The results of the multivariate regression analysis are presented (Table 6) with the variables that showed statistical significance in the prediction of phosphorus levels in the univariate analysis. This analysis shows how the variables being a woman, age, being single, married, separated/divorced, widowed, PI, anxiety, systolic blood pressure, potassium levels and inter-HD weight gain partly explain the variability of phosphorus levels (R2=23%, P=0.000). However, the only ones to show statistical significance were being female (P=0.014), age (P=0.000), PI (P=0.026), systolic blood pressure (P=0.016) and potassium levels (P=0.004).

Multivariate linear regression to identify predictors of p.

| B | Std. Error | p coefficients | p model | R2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.7999 | 0.945 | 0.059 | [12,0]0.000 | [12,0]0.237 | ||

| [6,0]Sociodemographic | Gender | Female | 0.464 | 0.187 | 0.014 | ||

| Age | Years | –0.026 | 0.006 | 0.000 | |||

| Single | 0.201 | 0.284 | 0.480 | ||||

| Married | 0.341 | 0.347 | 0.509 | ||||

| Cohabiting partner | 0.712 | 0.554 | 0.200 | ||||

| Separated/divorced | 0.804 | 0.496 | 0.107 | ||||

| Widowed | 0.020 | 0.261 | 0.940 | ||||

| [1,0]Psychological | Psychological inflexibility | 0.037 | 0.016 | 0.026 | |||

| Anxiety | 0.009 | 0.027 | 0.730 | ||||

| [2,0]Medical | SBP (mmHg) | 0.009 | 0.004 | 0.016 | |||

| K (mmol/l) | 0.316 | 0.109 | 0.004 | ||||

| Inter-HD weight gain (kg) | 0.113 | 0.131 | 0.389 |

HD: haemodialysis; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

In this study, we analysed the psychometric properties, reliability and validity of the Spanish version of the AAQ-II adapted to patients on HD. The data obtained provide good evidence that the adaptation of AAQHD-II is a valid and reliable measurement for assessing PI in the context of patients receiving this therapy. In general, the data are similar to the Spanish version of the questionnaire obtained by Ruiz et al.15 Specifically, the results showed that the AAQHD-II obtained: a) acceptable internal consistency; b) construct validity (parallel analysis recommended extracting only one single factor); and c) convergent validity, as it was correlated with both psychological symptoms (anxiety and depression) and the levels of health-related quality of life and its different sub-dimensions.

This is the first study in which PI levels have been assessed in patients on HD, this being a psychological construct of great interest for the study of psychopathology and quality of life in the area of chronic diseases.13,34 We specifically looked at how this construct might be associated with parameters related to treatment adherence and quality of life in this type of patient. A significant relationship was found between PI and the variables gender, quality of life, anxiety, depression, taking of psychiatric drugs, fat tissue index, phosphorus and interdialytic weight gain. Only anxiety, depression and phosphorus levels were independent predictors of PI levels in the multivariate model.

Also interesting was the relationship found between PI and P levels. In the multivariate linear analysis, PI presented as an independent predictor of P levels, which shows that this psychological characteristic could be an added factor to take into account in patients with poor control of P.

The lack of studies on the assessment of PI in the context of chronic renal failure makes comparison with other results impossible. However, it is relevant to mention other studies carried out in other chronic diseases on the relationships between that construct and different health and quality of life outcomes.

In two randomised controlled trials with diabetes patients it was found that patients who were trained in coping strategies for the promotion of psychological flexibility (mindfulness, acceptance strategies and clarification of values), reported better management of their diabetes (diet, exercise and glucose measurement) and achieving normal-range levels of glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) after this intervention.35

In obese and overweight patients, the application of strategies to promote psychological flexibility (cognitive distancing and acceptance of psychological reactions deriving from their disorder) resulted, at three and six months post-treatment, in significantly greater weight loss than that established in standard behavioural intervention programmes. Lillis et al. randomly assigned 84 overweight people who had lost weight in the previous two years to a waiting list control group or a mindfulness and acceptance workshop aimed at stigma related to obesity and psychological distress. After three months, patients who had participated in the intervention condition (mindfulness and acceptance) showed improvements in the stigma related to obesity, quality of life, psychological distress and body mass level, as well as improvements in tolerance to the anguish and greater psychological flexibility in the face of the difficulties associated with weight loss. The mediation analysis revealed that changes in coping strategies based on acceptance and psychological flexibility mediated changes in the outcomes.36,37

There have also been several studies in cancer in which interventions have been carried out to promote psychological flexibility and its relationship with better health outcomes in this type of patient. After performing an intervention based on ACT (identification of problematic thoughts/feelings, mindfulness and clarification of values/planning of activities in relation to these) in cancer patients, Feros et al. found improvements in the measurements assessed (psychological distress, depression, psychological flexibility and quality of life) after treatment and at the 3-month follow-up, compared to the pre-treatment assessment. The regression analysis showed that changes in the levels of psychological flexibility predicted changes in the variables quality of life, psychological distress and depression.38 In another study, in patients with high levels of anxiety-depression after reactivation of cancer, an intervention in promotion of psychological flexibility resulted in the improvement of a wide variety of not only negative aspects (anxiety, depression and specific cancer problems: fear of recurrence, cancer-related trauma symptoms and physical pain), but also positive aspects (vitality, sense of life meaning, comprehensibility, manageability). At the same time, changes in the levels of psychological flexibility related to cancer predicted most of the outcomes measured: depression (P=0.04), physical pain (P=0.03), traumatic impact of the cancer (P=0.01), vitality (P=0.03), life meaning (P=0.03) and manageability (P=0.04). It also nearly predicted changes in anxiety (P=0.06) and comprehensibility of life (P=0.08), which is consistent with the hypothesis of the mediating role of PI.20

The main limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, as conclusions can only be obtained based on the relationship or association between variables. In fact, it does not allow us to assess whether a higher PI is a consequence of the impact of problems related to the HD (treatment dependence, diet adherence, weight control, taking of medication, physical symptoms, etc.). Other limitations are the fact we included a wide range of patients (aged from 18 to 90), and that the sample includes very different profiles in terms of whether or not they are on the transplant waiting list. A stratification by age ranges and dividing the sample (patients on waiting list versus those who are not) would have given more specific information by groups.

The present findings also highlight the benefits of assessing PI in relation to a specific context. Future research could use the AAQHD-II to assess whether it shows better prediction or mediation in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, or even after an intervention promoting psychological flexibility in patients on HD.

The association found between PI and phosphorus opens up the possibility of new pathways for psychological intervention to improve the quality of life of these patients. Moreover, this highlights the importance of the interdisciplinary approach and the nephrologist-psychologist interaction in the care of patients with chronic renal failure.

ConclusionThe adaptation of the AAQ-II questionnaire to the HD context has produced a valid and reliable measure of PI for this type of patient. The results of this study contribute to the creation of a body of evidence supporting the role of PI in relation to health parameters and quality of life in chronic diseases. Further research is needed into the role of PI in patients with chronic renal failure on treatment with HD and its impact on health-related quality of life.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

To the patients of the Fresenius Medical Care clinics in Cordoba for participating in the study during their treatment hours and to the staff working in these clinics.

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II for patients on haemodialysis (AAQHD-II).

Below you will find a list of statements. Please rate how true each statement is for you by selecting a number next to it. Use the scale below to make your choice.

| Never true | Very seldom true | Sometimes true | Frequently true | Always true | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I try to avoid any thing or situation that reminds me of my dialysis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2. Worrying about dialysis takes up much of my time day to day | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3. I very frequently think about the fact that I depend on a dialysis machine | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4. My desire to drink is stronger than my willpower when it comes to controlling what I drink | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5. I can't stand the pressure of keeping to my diet | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6. I avoid doing any physical activity (walking, etc) for fear of not being able to do it | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7. I avoid social situations to control what I eat and drink | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Please cite this article as: Delgado-Domínguez CJ, Varas García J, Ruiz FJ, Díaz-Espejo B, Cantón-Guerrero P, Ruiz-Sánchez E, et al. Inflexibilidad psicológica e impacto clínico: adaptación del Cuestionario de Aceptación y Acción-II en una muestra de pacientes en tratamiento de hemodiálisis. Nefrologia. 2020;40:160–170.