Hyponatraemia is the most common electrolyte disorder. Some studies have found that it increases morbidity and mortality. There are new lines of research that are investigating the link between hyponatraemia and patient falls.

AimTo determine if hyponatraemia is associated with falls in elderly hospitalised patients.

MethodsDesign observational, analytical, case–control study.

Study populationPatients older than 65 years who had fallen during their hospitalisation at Gregorio Marañón Hospital (Madrid) were considered cases. Patients who did not fall were considered to be controls, paired according to the following variables: hospital ward, age, length of hospital stay, gender and Downton fall risk index. The sample size was 206 subjects.

Data collectionSocio-demographic factors, variables included in the falls record sheet, Downton fall risk index and sodium levels were studied (hyponatraemia was considered Na+<135mmol/l).

AnalysisA descriptive analysis was performed to determine the sample homogeneity. The OR was calculated, and an analytical analysis using Chi-square test and a multivariate logistic regression analysis were also performed.

ResultsOf 103 cases recruited, 61 were men (50.4%) and 42 were women (49.4%). Hyponatraemia was detected in 29 cases with an association with falls of P: 0.002. The adjusted OR was 3.708 (1.6–8.3), 95% CI. Risk factors for falls were identified as hyponatraemia and limb sensory deficits.

ConclusionsGiven that hyponatraemia could be considered a risk factor for falls, the inclusion of the determination of sodium level would be important for fall prevention strategies in the elderly.

La hiponatremia es el trastorno electrolítico más frecuente. Algunos estudios afirman que aumenta la morbimortalidad. Existen nuevas líneas de investigación que buscan la relación entre hiponatremia y caídas.

ObjetivoDeterminar si la hiponatremia es un factor relacionado con las caídas en ancianos hospitalizados.

MétodoDiseño observacional analítico de casos y controles.

Población de estudioSe consideraron casos los pacientes mayores de 65 años que experimentaron una caída durante su ingreso en unidades de hospitalización del Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón de Madrid. Los controles fueron pacientes que no wxperimentaron caída, pareados según las variables: unidad, edad, periodo de ingreso, género y Downton. El tamaño fue de 206 sujetos.

Recogida de datosSe estudiaron factores sociodemográficos, las variables incluidas en la ficha de registro de caídas y escala de Downton, y el sodio sérico. Se consideró hiponatremia Na+<135mmol/l.

AnálisisSe realizó un análisis descriptivo para valorar la homogeneidad de la muestra, un análisis analítico utilizando el test chi cuadrado, calculando la OR y un análisis multivariante con regresión logística.

ResultadosDe 103 casos, 61 eran hombres (50,4%) y 42 mujeres (49,4%). En 29 se detectó hiponatremia; la relación con las caídas fue p: 0,002. La OR ajustada fue de 3,708 (1,6–8,3), IC 95%. Se identificaron como factores de riesgo para las caídas: hiponatremia y déficits sensoriales en extremidades.

ConclusionesDado que la hiponatremia puede considerarse un factor de riesgo de caídas, sería importante valorar la inclusión de la determinación de sodio sérico dentro de las estrategias de prevención de caídas en ancianos.

The WHO defines a fall as the consequence of an involuntary event resulting in the person coming inadvertently to the ground.1

Falling is one of the risks patients have during their hospital stay. Even when falls do not cause injury, they may have a negative effect in elderly adults: restricting their physical activity and increasing the risk of another fall.2 Twenty-seven per cent (27%) of adults over the age of 65 fall once a year and 15% fall more than once a year.3

Falls are an important cause of morbidity and mortality, especially in people over the age of 65.1,4–7 There is evidence that 3.7% of hospitalised patients in Spain experience a fall,8 and intrinsic and extrinsic factors are involved in its aetiology.9 In a controlled hospital environment, accidental falls attributable to an extrinsic factor are much less common than non-accidental falls attributable to an intrinsic factor.2 The intrinsic factors include age-related physiological alterations, acute or chronic diseases, altered consciousness, difficulty walking and medication.10 Implementing and evaluating fall prevention protocols forms part of the safety strategy in the care of hospitalised patients.8

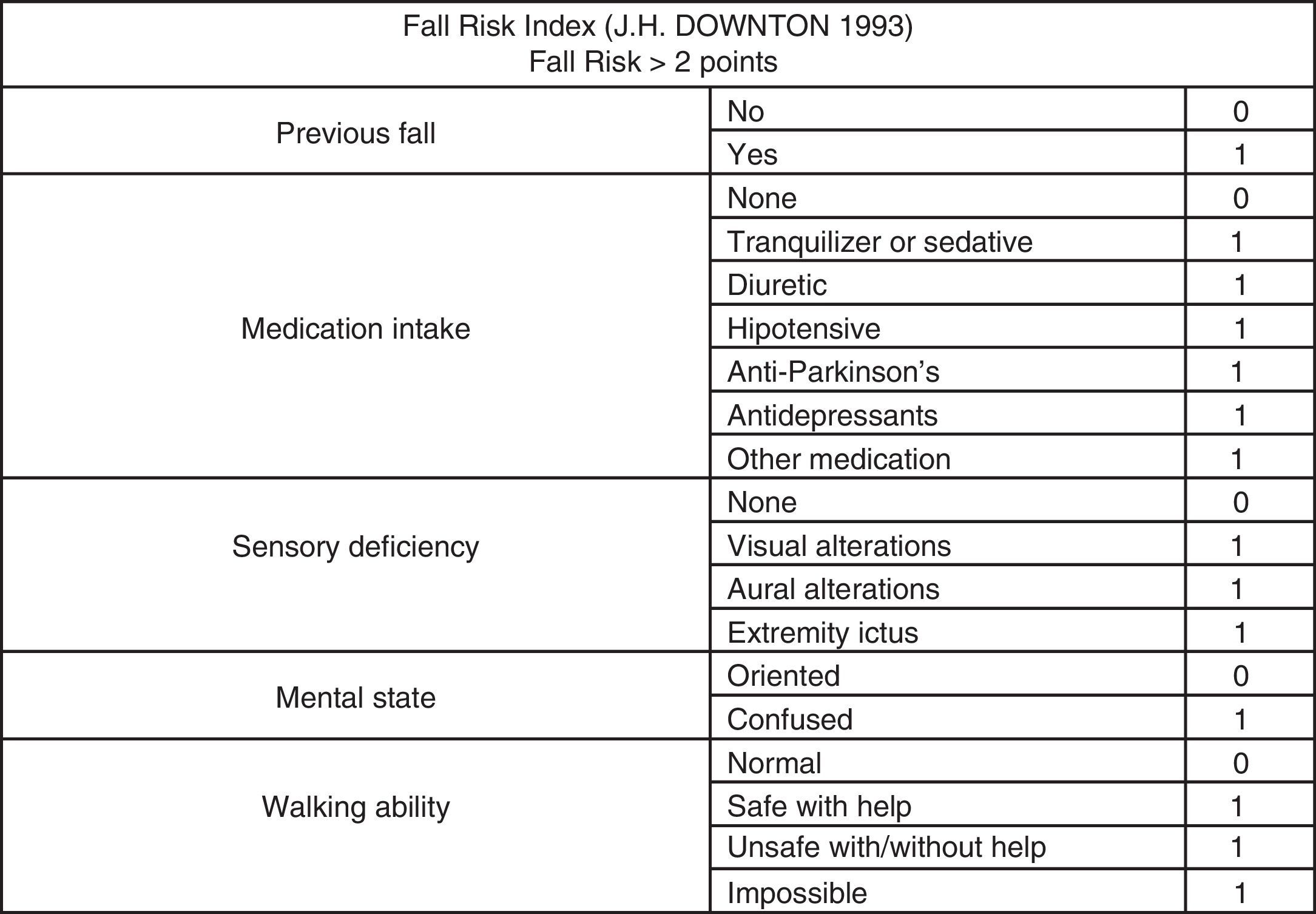

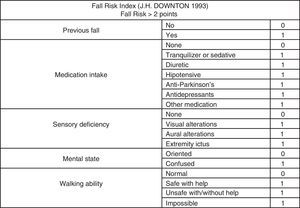

As there are multiple, predisposing physical risk factors for falls, it is essential to evaluate the risk of patients who have a fall to thus ensure that all the possible factors have been assessed.2 This risk is currently measured according to different scales in the hospitals in our setting. The scale used most often is the Downton Fall Risk Index,11 which does not include acute hyponatraemia among the items assessed. The manifestations of acute hyponatraemia include lethargy, confusion, gait instability, cognitive impairment and loss of consciousness.5,12,13 New evidence also associates hyponatraemia with bone demineralisation, recurrent falls and fractures; thus it should be considered an important independent risk factor for falls.5,6,14

Therefore, it must be determined whether hyponatraemia may be a risk factor to be systematically assessed and included in fall prevention protocols. Thus, the objective of this study is to determine whether hyponatraemia is a risk factor for falls in the hospitalised population over the age of 65.

Material and methodsType of designObservational, case–control, analytical study. The study period was from 1 April 2013 to 14 December 2013.

Study scopeThis study was carried out at the Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón of Madrid [Gregorio Marañón General University Hospital] at the following hospitalisation units: Internal Medicine, Digestive Unit, Neurology, Geriatrics, Orthogeriatrics, Neurosurgery, Medical Oncology and Cardiology.

Study populationWe included male and female patients over the age of 65 who were hospitalised at the Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón in Madrid, in the units mentioned above, who agreed to voluntarily participate in the study and gave their informed consent.

Case definition: patients hospitalised at one of the study units, over 65 years of age and who experienced a fall during their hospital stay.

Control definition: for case–control we selected a patient hospitalised in the same unit and during the same time period who had not fallen, and who was paired in terms of age, gender and modified Downton index score, thus enabling us to identify a patient with a high risk of falling when their score was 3 or greater (Fig. 1).

Sample size was estimated according to the following: OR (hyponatraemia/fall association: 2.8 obtained in a preliminary study); power of 90% and 95% confidence interval, with replacement of losses.

Sample size was 103 patient pairs of cases and controls.

The following information was obtained for both the patients and the control subjects:

- •

Sociodemographic data: age, gender, hospitalisation unit.

- •

Clinical data: serum sodium levels at the time of the fall or in the most recent analytical test conducted before the fall; for the control subjects we recorded the serum sodium level closest to the time they were included in the study and their modified Downton index score.

- •

Data from the centre's fall registry file: date of admission, previous falls, information on referral, limitations in mobility and walking, consciousness status, presence of sensory impairment, problems bowel problem's or urinary incontinence, drug or alcohol addiction, prescribed medication, safety devices required.

- •

For the cases of fall, the following variables were also considered: date and time of fall, whether they were alone, consequences, activity, environmental, safety and therapeutic devices at the time of the fall.

This study was approved by the Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón of Madrid Independent Ethics Committee.

Data collectionWhen a fall occurred, it was reported to a team member and, after obtaining informed consent, all the study variables were collected. In parallel, a control subject was recruited who had given prior consent, and the same information was recorded for the control subject except for the information regarding the environment, circumstances and consequences of the fall.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was carried out using the Access and SPSS V.21 for Windows computer programmes (IBM1 Corporation, New York, U.S.A.).

Hyponatraemia was defined as serum Na+ values <135mmol/l.14

A descriptive statistical analysis of the variables was carried out, with frequencies and percentages in the case of qualitative variables; mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range, according to distribution for qualitative variables. Frequencies were compared with the Chi-squared test in the case of qualitative variables and with the Student's t-test for quantitative variables. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To quantify the magnitude of the association between the different variables studied, the results are presented with their odds ratio (OR) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

A bivariate and multivariate analysis was carried out (adjusted for potential confounding factors) by a binary logistic regression model using the method to be introduced, extracting from the model those variables that presented higher p-values, and calculating the raw ORs adjusted for each of the factors included.

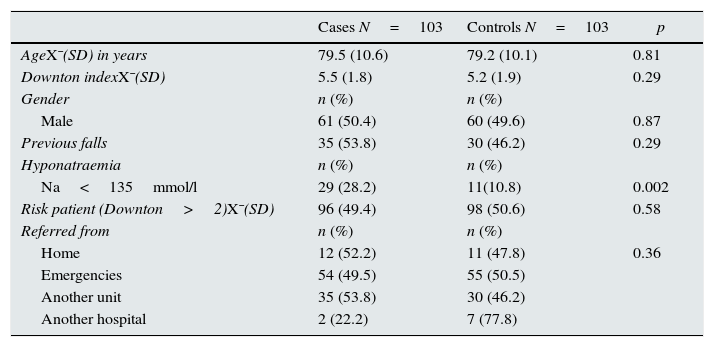

ResultsDuring the study period 4415 patients were admitted and 135 falls occurred. Table 1 describes the sociodemographic and clinical variables of the groups of cases and controls, and shows that there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups with regard to these variables, so the groups were homogenous.

Sociodemographic and clinical variables of the case group and controls. Analysis of homogeneity between groups.

| Cases N=103 | Controls N=103 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AgeX¯(SD) in years | 79.5 (10.6) | 79.2 (10.1) | 0.81 |

| Downton indexX¯(SD) | 5.5 (1.8) | 5.2 (1.9) | 0.29 |

| Gender | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Male | 61 (50.4) | 60 (49.6) | 0.87 |

| Previous falls | 35 (53.8) | 30 (46.2) | 0.29 |

| Hyponatraemia | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Na<135mmol/l | 29 (28.2) | 11(10.8) | 0.002 |

| Risk patient (Downton>2)X¯(SD) | 96 (49.4) | 98 (50.6) | 0.58 |

| Referred from | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Home | 12 (52.2) | 11 (47.8) | 0.36 |

| Emergencies | 54 (49.5) | 55 (50.5) | |

| Another unit | 35 (53.8) | 30 (46.2) | |

| Another hospital | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.8) |

Na: sodium.

p significance level<0.05.

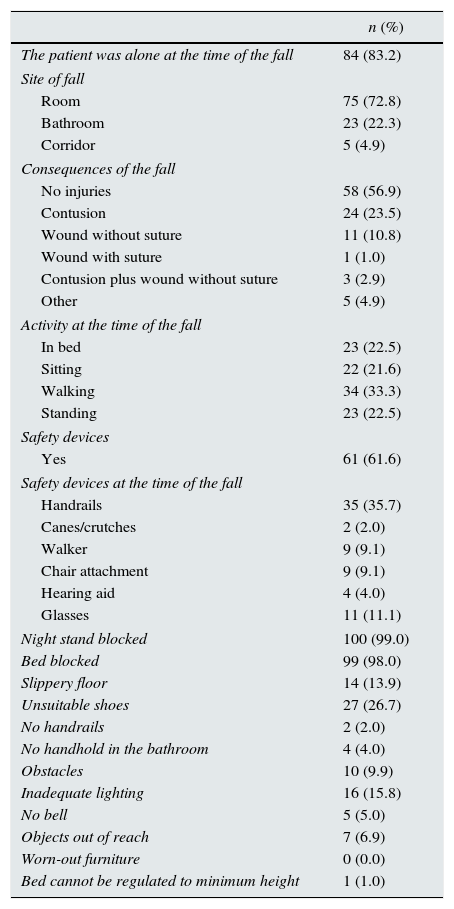

In terms of the fall results, Table 2 shows that more than half of the falls had no consequences and only one resulted in a wound that needed to be sutured. The rest of the environmental characteristics and the time of the fall suggest that the greatest number of falls occurred in the patient's room, when he or she was walking around and the most typical safety devices were in place.

Characteristics of the fall and environment where it occurred.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| The patient was alone at the time of the fall | 84 (83.2) |

| Site of fall | |

| Room | 75 (72.8) |

| Bathroom | 23 (22.3) |

| Corridor | 5 (4.9) |

| Consequences of the fall | |

| No injuries | 58 (56.9) |

| Contusion | 24 (23.5) |

| Wound without suture | 11 (10.8) |

| Wound with suture | 1 (1.0) |

| Contusion plus wound without suture | 3 (2.9) |

| Other | 5 (4.9) |

| Activity at the time of the fall | |

| In bed | 23 (22.5) |

| Sitting | 22 (21.6) |

| Walking | 34 (33.3) |

| Standing | 23 (22.5) |

| Safety devices | |

| Yes | 61 (61.6) |

| Safety devices at the time of the fall | |

| Handrails | 35 (35.7) |

| Canes/crutches | 2 (2.0) |

| Walker | 9 (9.1) |

| Chair attachment | 9 (9.1) |

| Hearing aid | 4 (4.0) |

| Glasses | 11 (11.1) |

| Night stand blocked | 100 (99.0) |

| Bed blocked | 99 (98.0) |

| Slippery floor | 14 (13.9) |

| Unsuitable shoes | 27 (26.7) |

| No handrails | 2 (2.0) |

| No handhold in the bathroom | 4 (4.0) |

| Obstacles | 10 (9.9) |

| Inadequate lighting | 16 (15.8) |

| No bell | 5 (5.0) |

| Objects out of reach | 7 (6.9) |

| Worn-out furniture | 0 (0.0) |

| Bed cannot be regulated to minimum height | 1 (1.0) |

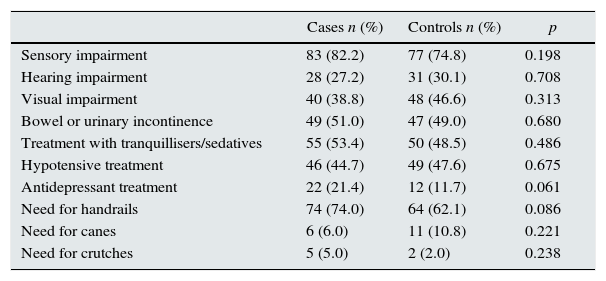

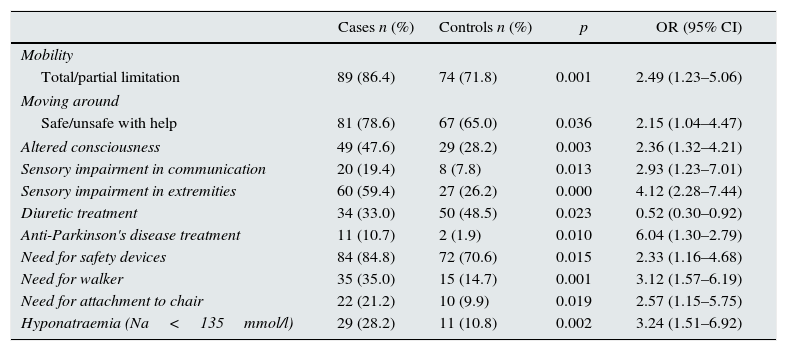

Tables 3 and 4 show the results of the bivariate analysis. Table 3 shows the values of the factors that did not have statistical significance, and Table 4 shows those that did obtain a statistically significant relationship and were subsequently included in the regression model.

Variables in which no significant differences were found between the two groups and hospital fall.

| Cases n (%) | Controls n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensory impairment | 83 (82.2) | 77 (74.8) | 0.198 |

| Hearing impairment | 28 (27.2) | 31 (30.1) | 0.708 |

| Visual impairment | 40 (38.8) | 48 (46.6) | 0.313 |

| Bowel or urinary incontinence | 49 (51.0) | 47 (49.0) | 0.680 |

| Treatment with tranquillisers/sedatives | 55 (53.4) | 50 (48.5) | 0.486 |

| Hypotensive treatment | 46 (44.7) | 49 (47.6) | 0.675 |

| Antidepressant treatment | 22 (21.4) | 12 (11.7) | 0.061 |

| Need for handrails | 74 (74.0) | 64 (62.1) | 0.086 |

| Need for canes | 6 (6.0) | 11 (10.8) | 0.221 |

| Need for crutches | 5 (5.0) | 2 (2.0) | 0.238 |

p significance level<0.05.

Odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals of the variables in which an association was found with falls between the two groups.

| Cases n (%) | Controls n (%) | p | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility | ||||

| Total/partial limitation | 89 (86.4) | 74 (71.8) | 0.001 | 2.49 (1.23–5.06) |

| Moving around | ||||

| Safe/unsafe with help | 81 (78.6) | 67 (65.0) | 0.036 | 2.15 (1.04–4.47) |

| Altered consciousness | 49 (47.6) | 29 (28.2) | 0.003 | 2.36 (1.32–4.21) |

| Sensory impairment in communication | 20 (19.4) | 8 (7.8) | 0.013 | 2.93 (1.23–7.01) |

| Sensory impairment in extremities | 60 (59.4) | 27 (26.2) | 0.000 | 4.12 (2.28–7.44) |

| Diuretic treatment | 34 (33.0) | 50 (48.5) | 0.023 | 0.52 (0.30–0.92) |

| Anti-Parkinson's disease treatment | 11 (10.7) | 2 (1.9) | 0.010 | 6.04 (1.30–2.79) |

| Need for safety devices | 84 (84.8) | 72 (70.6) | 0.015 | 2.33 (1.16–4.68) |

| Need for walker | 35 (35.0) | 15 (14.7) | 0.001 | 3.12 (1.57–6.19) |

| Need for attachment to chair | 22 (21.2) | 10 (9.9) | 0.019 | 2.57 (1.15–5.75) |

| Hyponatraemia (Na<135mmol/l) | 29 (28.2) | 11 (10.8) | 0.002 | 3.24 (1.51–6.92) |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; Na: sodium; OR: odds ratio.

p significance level<0.05.

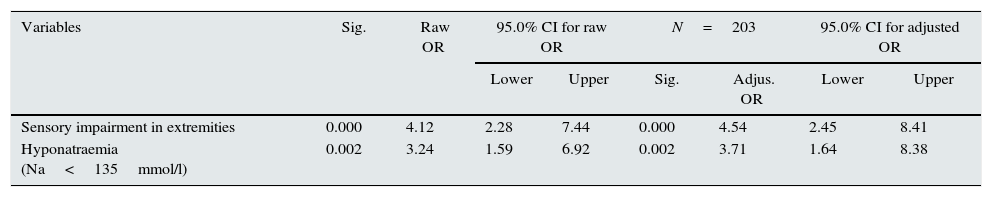

Once the data had been analysed with the logistic regression model and any possible confounding factors had been removed, we found an association between falls and the following variables: sensory impairment in extremities and hyponatraemia (Table 5).

Adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals of the variables in which an association was found with falls between the two groups.

| Variables | Sig. | Raw OR | 95.0% CI for raw OR | N=203 | 95.0% CI for adjusted OR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Sig. | Adjus. OR | Lower | Upper | |||

| Sensory impairment in extremities | 0.000 | 4.12 | 2.28 | 7.44 | 0.000 | 4.54 | 2.45 | 8.41 |

| Hyponatraemia (Na<135mmol/l) | 0.002 | 3.24 | 1.59 | 6.92 | 0.002 | 3.71 | 1.64 | 8.38 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; Na: sodium; OR: odds ratio.

p significance level<0.05.

In this study we found an association between hyponatraemia and falls. We also showed the relationship between falls and sensory impairment in the extremities. This association was independent from other factors, such as: medications, auditory impairment in communication or visual impairment and continence problems. Therefore, it can be concluded that hyponatraemia is a risk factor for falls.

The manifestations of acute hyponatraemia include lethargy, confusion, gait instability and loss of consciousness. These are all symptoms that are assessed using the Downton fall risk index, but they are not identified as symptoms of a disease requiring early treatment, such as hyponatraemia; rather, they are considered to be symptoms related to patient's age and physical status that lead to the application of restrictive measures and adapting the environment to prevent falls. Additionally, hyponatraemia has traditionally been considered asymptomatic and its treatment, unnecessary.5,12,13

In view of our results, patients should be evaluated clinically including in the differential diagnosis whether the symptoms and risk factors presented are due to a state of hyponatraemia or other reasons.

Until 2006, only one study had investigated the association between falls and the presence of hyponatraemia.5,6,15 In recent years, studies have emerged demonstrating that hyponatraemia is an important independent risk factor for falls and is related to fractures.5,6,16 The results obtained are consistent with these conclusions, considering hyponatraemia and sensory impairment to be risk factors that directly impact falls.

In Spain, approximately 30% of people over the age of 65 fall once a year, and, of these, 50% fall again in the same year.2,3 Given this high prevalence and considering that falls are more common in institutionalised elderly patients,2 the conclusions of this study take on special clinical relevance: there are great repercussions in the safety of the most vulnerable patients, as falls are an important source of comorbidity and deterioration in quality of life.3

Certain physical conditions and environmental situations have been described in the literature which are predisposing factors for falls and can be modified, such as the intake of some drugs, activity level and the environment.2 Therefore, while elderly patients are hospitalised they should be routinely asked about falls, the risk should be evaluated and the underlying factors susceptible to change should be approached.

According to the Pharmacovigilance centre of the Community of Madrid, since the year 1992 there has been a 70% increase in the cases of hyponatraemia attributable to drugs, and half of these cases occurred in patients over the age of 75. The most related drugs are antidepressants (33%), diuretics (35%), desmopressin (28%) and antiepileptic drugs (26%). However, in our study we did not find a direct relationship between taking drugs and falls.

The need and importance of implementing programmes that guarantee patient safety is incontestable, including fall prevention.8,17 To this end, effective tools must be created to assess the risks factors for falls in hospitalised patients.

In view of the above, and as a result of the data provided by this study, we believe that hyponatraemia is a risk factor for falls and serum sodium should be determined and included in the falls risk assessment scales, and be part of the fall prevention strategies in the elderly.

Lastly, it should be highlighted that efficiency has become one of the main concerns of healthcare managers, which has led to a major upsurge in financial assessment analyses in the last decade. Therefore, since healthcare costs must be considered among the reasons for implementing the measures proposed, we believe that cost studies should be conducted, enabling us to evaluate the efficiency of including serum sodium measurements in fall risk scales.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Elena Calderari Fernándeza, Laura Collados-Gómezb, Eulalia García-Peñac, Yassira Gracia San Románd, Giovanna Herranz-Borregoe, Dolores Isac Pérezf, Margarita Medina-Torresa, Esther Quirós Abajog, Cristina Sanz de Luish.

a Nursing Group, Gregorio Marañón Healthcare Research Institute of Madrid.

b Preventative Medicine and Quality Management Service, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón of Madrid. Gregorio Marañón Healthcare Research Institute.

c Geriatrics Service, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón of Madrid.

d Orthogeriatrics Service, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón. Gregorio Marañón Healthcare Research Institute of Madrid.

e Internal Medicine Service, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón of Madrid.

f Psychiatric Service, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón of Madrid.

g Oncology Service, Hospital Ramón y Cajal of Madrid.

f Cardiology Service, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón of Madrid.

You can view a list of members of the Corporate Group PRECAHI in Annex A.

Pease cite this article as: Lobo-Rodríguez C, García-Pozob AM, Gadea-Cedenillac C, Moro-Tejedorb MN, Pedraz Marcosd A, Tejedor-Jorgee A, et al. Prevalencia de hiponatremia en pacientes mayores de 65 años que sufren una caída intrahospitalaria. Nefrología. 2016;36:292–298.