Resistant hypertension (RH) is a common problem in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). A decline in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and increased albuminuria are associated with RH; however, there are few published studies about the prevalence of this entity in patients with CKD.

ObjectiveTo estimate the prevalence of RH in patients with different degrees of kidney disease and analyse the characteristics of this group of patients.

MethodsA total of 618 patients with hypertension and CKD stages I–IV were enrolled, of which 82 (13.3%) met the criteria for RH.

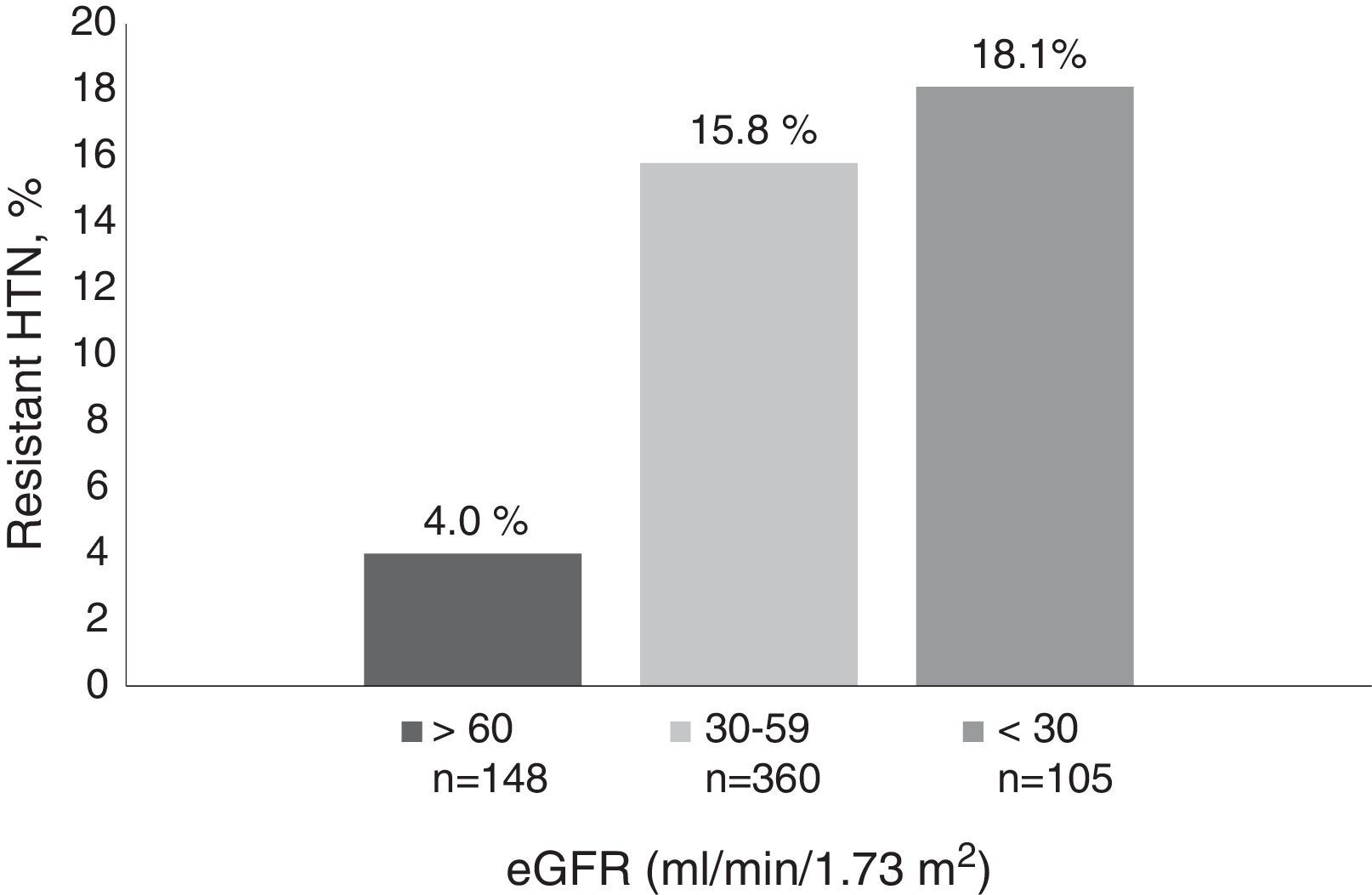

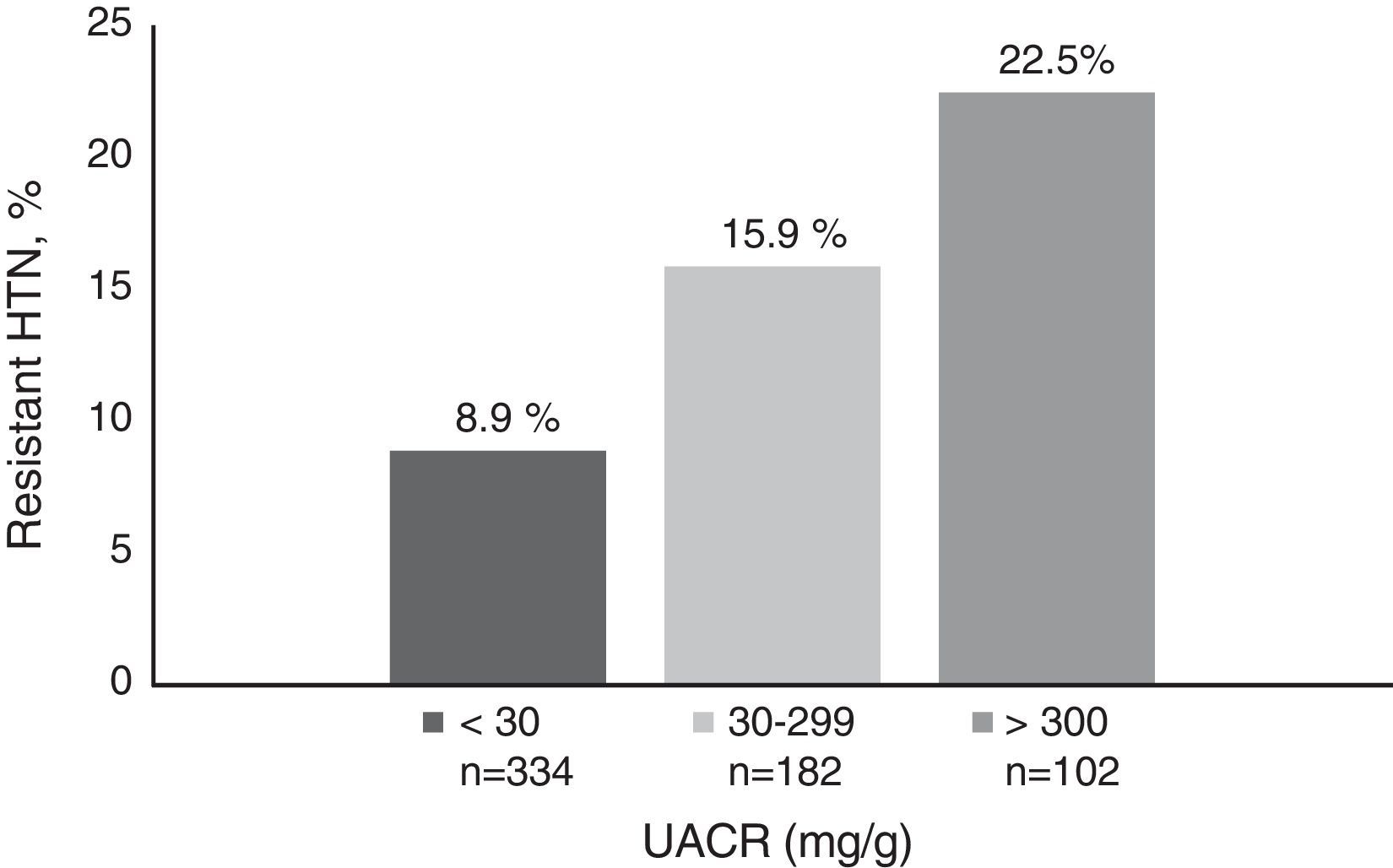

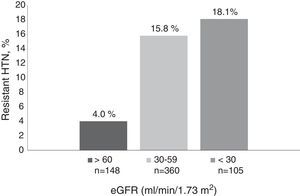

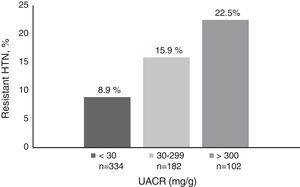

ResultsRH prevalence increased significantly with age, the degree of CKD and albuminuria. The prevalence of RH was 3.2% in patients under 50 years, 13.8% between 50 and 79 years and peaked at 17.8% in patients older than 80 years. Renal function prevalence was 4%, 15.8% and 18.1% in patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of >60, 30–59 and <30ml/min/1.73m2, respectively, and 8.9%, 15.9% and 22.5% for a urine albumin to creatinine ratio (UACR) <30, 30–299 and >300mg/g respectively. In a logistic regression model, the characteristics associated with resistant hypertension were age, history of cardiovascular disease, GFR, albuminuria and diabetes mellitus. A total of 47.5% of patients with resistant hypertension had controlled BP (<140/90mmHg) with 4 or more antihypertensive drugs. These patients were younger, with better renal function, less albuminuria and received more aldosterone antagonists.

ConclusionRH prevalence increases with age, the degree of CKD and albuminuria. Strategies such as treatment with aldosterone receptor antagonists are associated with better blood pressure control in this group of patients, leading to reduced prevalence.

La hipertensión arterial (HTA) resistente en un problema frecuente en pacientes con enfermedad renal crónica (ERC). El descenso del filtrado glomerular (FGe) y el incremento en la albuminuria se asocian a HTA resistente, sin embargo, hay pocos estudios publicados sobre la prevalencia de esta entidad en los pacientes con ERC.

ObjetivoEstimar la prevalencia de la HTA resistente en pacientes con diferentes grados de enfermedad renal y analizar sus características.

MétodosSe incluyó a 618 pacientes con HTA y ERC estadios i-iv, de los cuales 82 (13,3%) cumplían criterios de HTA resistente.

ResultadosLa prevalencia de HTA resistente se incrementó de forma significativa con la edad, el grado de ERC y la albuminuria. La prevalencia de HTA resistente fue del 3,2% en pacientes menores de 50 años, del 13,8% entre 50 y 79 años, y alcanzó el 17,8% en mayores de 80 años. En relación con la función renal, la prevalencia fue del 4, del 15,8 y del 18,1%, en pacientes con filtrado glomerular estimado (FGe) de >60, de 30-59 y de <30ml/min/1,73 m2, respectivamente y de 8,9, 15,9 y 22,5% para índice albúmina/creatinina urinario (UACR) < 30, 30-299 y > 300mg/g, respectivamente. En un modelo de regresión logística las características que se asociaron con la HTA resistente fueron la edad, el antecedente de enfermedad cardiovascular, el FGe, la albuminuria y la diabetes mellitus. El 47,5% de los pacientes con HTA resistente tenían la PA controlada (<140/90 mmHg) con 4 o más fármacos antihipertensivos. Estos pacientes eran más jóvenes, con mejor función renal, menos albuminuria y recibían con más frecuencia antagonistas de la aldosterona.

ConclusiónLa prevalencia de HTA resistente aumenta con la edad, el grado de ERC y la albuminuria. Estrategias como el tratamiento con antagonistas de receptores de aldosterona se asocian con un mejor control tensional en este grupo de pacientes y disminuyen su prevalencia.

Resistant hypertension (HTN), defined as the lack of control of blood pressure (BP>140/90mmHg) despite treatment with 3 or more antihypertensive drugs, including a diuretic, or BP controlled using more than 4 drugs,1 is a common problem in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Studies conducted in the general population estimate the prevalence of resistant HTN within a wide range of 10% and 30% of all hypertensive patients. The 2005–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) estimated that resistant HTN affects 12.3% of patients with HTN,2 and according to the Spanish ambulatory blood pressure monitoring registry, the prevalence is 12.2%.3 Population studies such as the Framingham Heart Study4 or the NHANES have identified race, age, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease and CKD as factors associated with resistant HTH.

In the study by Tanner et al., using data from patients enrolled in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study, at estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)<60ml/min/1.73m2 and an urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR)>300mg/g were significantly associated with the presence of resistant HTN.5 Although both CKD and proteinuria have been associated with refractory HTN, there are only few studies on this group of patients and in Spain there is no study evaluating the prevalence of resistant HTN in patients with CKD.

Our study aimed at estimating the prevalence of resistant HTN in a cohort of patients followed in outpatient nephrology clinics with varying degrees of CKD. We have evaluated the characteristics of patients with CKD and resistant HTN, and factors associated with refractoriness BP of control.

Patients and methodsStudy designRetrospective observational of 618 consecutive patients with stable HTN and CKD, stages I–IV, followed in outpatient nephrology clinics from 1 January 2012 until 31 December 2012.

Inclusion criteria: age≥18 years, CKD (stages I–IV) and HTN. Exclusion criteria: hospitalisation in the 4 months prior to inclusion or refusal to participate in the study.

CKD has been defined according to the KDOQI guidelines6 and HTN according to the Eighth Joint National Committee report7 as BP>140/90mmHg in this group of patients with CKD or receiving treatment with antihypertensive drugs. Controlled HTN was defined as BP values <140/90mmHg at the clinic.

Patients who met criteria for resistant HTN according to the 2008 American Heart Association guidelines (BP>140/90mmHg) were selected, despite the combined use of 3 antihypertensive drugs of different therapeutic classes at maximum doses, including a diuretic, or patients treated with 4 or more antihypertensive drugs were selected, regardless of arterial BP values.

At the nephrology clinic, all the medication was reviewed with the patient, ensuring the dose and time of administration, in order to improve treatment compliance.

Aldosterone antagonists were used in patients with a stable eGFR and potassium levels <4.5mEq/L.

Variables studiedPatients’ demographic data and clinical records, such as age, sex, smoking habits, in-clinic BP, diabetes mellitus and history of cardiovascular disease (heart failure, ischaemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease and cerebrovascular disease), were collected. Heart failure was diagnosed by chest X-ray (presence of pulmonary oedema) and echocardiogram (left ventricular dysfunction). Patients were considered to have heart failure if they had symptoms or functional class II to IV based on the New York Heart Association's classification, with an ejection fraction <45%. Cerebrovascular disease was defined by history of ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke, transient ischaemic attack, or carotid artery stenosis >70% (measured by Doppler ultrasound). Patients with intermittent claudication, stenosis of the major arteries of the legs in arteriography or Doppler ultrasound, presence of ulcers caused by atherosclerotic disease, revascularisation or amputation due to ischaemia were diagnosed of peripheral vascular disease.

Renal function was assessed by eGFR using the 4-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation, and patients were separated by the degree of renal dysfunction into 3 groups: eGFR>60, 30–59 and <30ml/min/1.73m2. Albuminuria was measured with immunonephelometry. We used the UACR to assess albuminuria and patients were divided into 3 groups: UACR 0–29, 30–299 and >300mg/g. The nutritional and inflammatory parameters of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides and C-reactive protein (CRP) were collected from samples obtained at baseline after 8h of fasting. Biochemical parameters were analysed with auto-analysers using standard methods, and plasma CRP was measured using a turbidimetric immunoassay with latex on a Hitachi analyser (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Missouri, United States).

In-clinic BP was measured using an automatic electronic sphygmomanometer (Omron MX3 Omron Life Science, Kyoto, Japan). In all patients, there were 3 BP measurements taken, after 10min of rest with the patient sitting and 2min interval for each BP measurement and the final value was considered the mean of the second and third reading.

Antihypertensive drugs and statin therapy were recorded.

Statistical analysisCentral tendency statistics were used: arithmetic mean±standard deviation for continuous variables and frequency distribution for discrete variables. To compare means across the different groups, a Student's t-test was used, for the binary independent variables, and to compare proportions, a Pearson's Chi2 test was used. A logistic regression model was used to identify variables independently associated with resistant HTN. The logistic multiple regression analysis was carried out by using the ENTER method to introduce all independent variables that were statistically significant in the univariate model with a value of p<0.05 into the model. For the statistical analysis, SPSS for Windows, version 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, United States), was used.

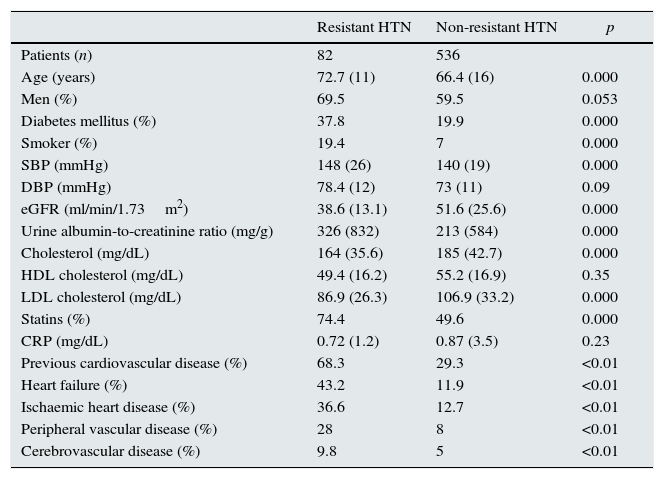

ResultsThe study included 618 patients with HTN and CKD, stages I–IV (24% in stages I and II; 58.7% in stage III and 17.3% in stage IV), 82 of whom (13.3%) met the criteria for resistant HTN. Patients with resistant HTN compared with the rest of the hypertensive patients were older: 72.7±11 years vs. 66.4±16 years (p<0.01), with a greater proportion of diabetes (37.8 vs. 19.9%; p<0.01) and with cardiovascular disease (68.3 vs. 29.3%; p<0.01). Patients with resistant HTN received more statins, 74.4% vs. 49.6% (p<0.01) and had lower LDL cholesterol (86.9±26.3 vs. 106.9±33.2mg/dL; p<0.01). These patients had worse renal function (eGFR 38.6±13.1 vs. 51.6±25.6ml/min/m2; p<0.01) and higher albuminuria (UACR 326±832 vs. 231±584mg/g; p<0.01) (see Table 1). Poor BP control in patients with resistant HTN is due to an increase in SBP (148±26 vs. 140±19mmHg; <0.01), since 98% of these patients have controlled DBP<90mmHg.

Characteristics of patients with and without resistant HTN.

| Resistant HTN | Non-resistant HTN | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 82 | 536 | |

| Age (years) | 72.7 (11) | 66.4 (16) | 0.000 |

| Men (%) | 69.5 | 59.5 | 0.053 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 37.8 | 19.9 | 0.000 |

| Smoker (%) | 19.4 | 7 | 0.000 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 148 (26) | 140 (19) | 0.000 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 78.4 (12) | 73 (11) | 0.09 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 38.6 (13.1) | 51.6 (25.6) | 0.000 |

| Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (mg/g) | 326 (832) | 213 (584) | 0.000 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 164 (35.6) | 185 (42.7) | 0.000 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 49.4 (16.2) | 55.2 (16.9) | 0.35 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 86.9 (26.3) | 106.9 (33.2) | 0.000 |

| Statins (%) | 74.4 | 49.6 | 0.000 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.72 (1.2) | 0.87 (3.5) | 0.23 |

| Previous cardiovascular disease (%) | 68.3 | 29.3 | <0.01 |

| Heart failure (%) | 43.2 | 11.9 | <0.01 |

| Ischaemic heart disease (%) | 36.6 | 12.7 | <0.01 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (%) | 28 | 8 | <0.01 |

| Cerebrovascular disease (%) | 9.8 | 5 | <0.01 |

eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; SBP: systolic blood pressure; CRP: C-reactive protein.

The prevalence of resistant HTN increased significantly with age, degree of CKD and albuminuria. The prevalence of resistant HTN was 3.2% in patients <50 years old, 13.8% in patients between 50 and 79 years old, and 17.8% in patients >80 years old. As for renal function, prevalence was 4%, 15.8% and 18.1% in patients with eGFRs of >60, 30–59 and <30ml/min/1.73m2, respectively (Fig. 1) and 8.9%, 15.9% and 22.5% for UACR <30, 30–299 and >300mg/g, respectively (Fig. 2).

With regard to antihypertensive treatment, patients with refractory HTN received on average 4.2±0.5 drugs/patient vs. 1.6±0.9 drugs/patient in the rest (p<0.01). Among patients with resistant HTN, 100% were treated with one or more diuretics (69.5% loop diuretics and 39.1% thiazides), 91.4% with a blocker of the renin–angiotensin system, 72% with calcium channel blockers, 61.2% with beta-blockers and 18.8% with aldosterone antagonists. In all, 29.5% of patients received treatment with the combination of 2 or more diuretics.

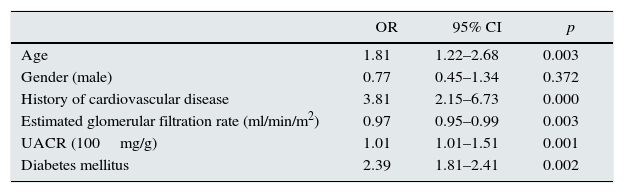

In a logistic regression model, the factors that increased the risk of resistant HTN were age (OR 1.81; CI 1.22–2.68), history of cardiovascular disease (OR 3.81; CI 2.15–6.73), albuminuria (OR 1.01; CI 1.21–1.51) and diabetes mellitus (OR 2.39; CI 1.81–2.41). Better renal function reduced the risk of resistant HTN (OR 0.97; CI 0.95–0.99) (Table 2).

Multiple logistic regression analysis with the characteristics associated with resistant HTN.

| OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.81 | 1.22–2.68 | 0.003 |

| Gender (male) | 0.77 | 0.45–1.34 | 0.372 |

| History of cardiovascular disease | 3.81 | 2.15–6.73 | 0.000 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (ml/min/m2) | 0.97 | 0.95–0.99 | 0.003 |

| UACR (100mg/g) | 1.01 | 1.01–1.51 | 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.39 | 1.81–2.41 | 0.002 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

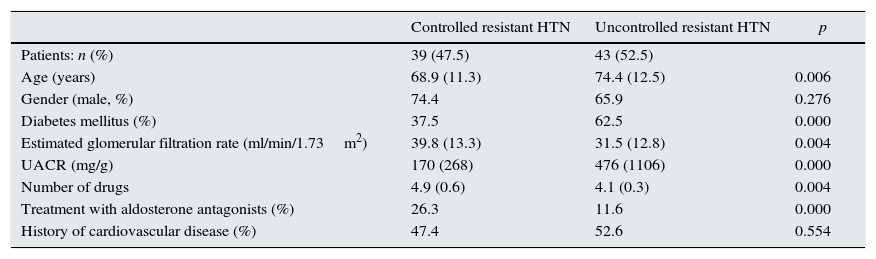

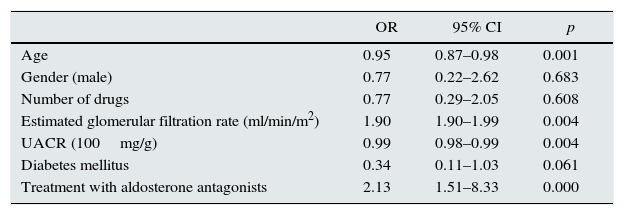

In total, 47.5% of patients with resistant HTN who received 4 or more antihypertensive drugs had controlled BP. When comparing this group of patients with patients with uncontrolled refractory HTN, we found that they were younger (68.9±11.3 vs. 74.4±12.5 years, p<0.01), had a lower proportion of diabetics (37.5 vs. 62.5%), had better renal function (eGFR 39.8±13.3 vs. 31.5±12.8ml/min/1.73m2; p<0.01) and received more receptor antagonists aldosterone (26.3% vs. 11.6%; p<0.001) (Table 3). These factors maintained their predictive power in a logistic regression model, apart from diabetes mellitus (Table 4).

Characteristics of patients with resistant HTN and controlled and uncontrolled BP<140/90mmHg.

| Controlled resistant HTN | Uncontrolled resistant HTN | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients: n (%) | 39 (47.5) | 43 (52.5) | |

| Age (years) | 68.9 (11.3) | 74.4 (12.5) | 0.006 |

| Gender (male, %) | 74.4 | 65.9 | 0.276 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 37.5 | 62.5 | 0.000 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (ml/min/1.73m2) | 39.8 (13.3) | 31.5 (12.8) | 0.004 |

| UACR (mg/g) | 170 (268) | 476 (1106) | 0.000 |

| Number of drugs | 4.9 (0.6) | 4.1 (0.3) | 0.004 |

| Treatment with aldosterone antagonists (%) | 26.3 | 11.6 | 0.000 |

| History of cardiovascular disease (%) | 47.4 | 52.6 | 0.554 |

Variables associated with control of BP<140/90mmHg in patients with resistant HTN.

| OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.95 | 0.87–0.98 | 0.001 |

| Gender (male) | 0.77 | 0.22–2.62 | 0.683 |

| Number of drugs | 0.77 | 0.29–2.05 | 0.608 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (ml/min/m2) | 1.90 | 1.90–1.99 | 0.004 |

| UACR (100mg/g) | 0.99 | 0.98–0.99 | 0.004 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.34 | 0.11–1.03 | 0.061 |

| Treatment with aldosterone antagonists | 2.13 | 1.51–8.33 | 0.000 |

Potassium levels were higher in patients treated with spironolactone (4.5±0.8 vs. 4.2±0.7mEq/L; p=0.48), but the difference was not statistically significantly.

DiscussionOur study shows that the prevalence of resistant HTN increases in patients with more advanced CKD and proteinuria. Still, the prevalence of resistant HTN in our patients was much lower than previously described in patients with CKD. Strategies such as treatment with aldosterone receptor antagonists improve the degree of BP control in patients with resistant HTN.

The prevalence of resistant HTN in our study, conducted in patients with CKD in stages I–IV was 13.3%, similar to that estimated in studies in hypertensive patients without CKD, such as the NHANES1 (12.3%) or the Spanish ambulatory blood pressure monitoring registry, published in 20112 (9.9% in patients with HTN and 12.9% in hypertensive patients with treatment). We consider the prevalence of refractory HTN in our series to be low, as it is very similar to that described in the general population, but much lower than that described in patients with CKD.

As mentioned above, we found that there is a direct link between the degree of CKD, albuminuria and the prevalence of resistant HTN. The study4 showed this same relationship, with a significant and progressive increase in the prevalence of resistant HTN as the CKD progresses in 15.8%, 24.9% and 33.4% for eGFR >60, 45–69 and <45ml/min/1.73m2, respectively. The increase in albuminuria was also associated with an increase in refractory HTN, with a prevalence of 12.1%, 20.8%, 27.7% and 48.3% for a UACR <10, of 10–29, 30–299 and >300mg/g, respectively. In our study, the prevalence is much lower in all stages and in all groups (see Figs. 1 and 2). This fact is probably related to better treatment compliance by patients attending a specialised clinic8 and to the development of therapeutic strategies that improve BP control in patients with resistant HTN, such as optimising diuretic therapy, decreasing salt intake or treating with aldosterone blockers, as noted in a recent review published by Rossignol et al.9: these are key points to reduce BP values in patients with resistant HTN and CKD.

In a previous study conducted by our group we showed that bioimpedance-guided intensification of diuretic therapy improved BP control of patients with resistant HTN and CKD.10 In addition, 18.8% of our patients were treated with spironolactone, i.e. a figure well above the 3% of patients enrolled in the NHANES1 or the 9% in the Spanish register of hypertensive patients in primary care.11 Aldosterone antagonists are the standard in controlling BP and proteinuria in patients with refractory HTN, and this fact has been demonstrated in several studies.12,13 In more recent studies like SYMPLICITY HTN-3,14 conducted in highly selected patients with refractory HTN, that assess the efficacy of renal sympathetic denervation, one quarter of the patients received such treatment. In patients with CKD, potassium levels must be closely monitored in patients on spironolactone, but it has been shown that this treatment significantly reduces BP and proteinuria.15,16 In our patients, potassium levels were higher in those who were treated with spironolactone (4.5±0.8 vs. 4.2±0.7mEq/L; p=0.48), but this difference was not significant, and there were no cases of toxic hyperkalaemia. In all probability, repeated dietary advice and the use of ion exchange resins, as well as very close monitoring, have caused there to be no differences in potassium levels.

The other factors associated with a higher prevalence of resistant HTN were age, diabetes mellitus, treatment with statins and increased cardiovascular risk. Older age was associated with worse BP control, especially due to poor control of SBP. The association between age and poor control of SBP is well known.17 BP increases progressively with age, due to increased arterial stiffness, baroreceptor dysfunction, endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress. In studies such as ALLHAT,18 DM was also associated with poor BP control. In several studies, metabolic syndrome has been related to the presence of refractory HTN, often associated with elevated aldosterone levels.19 In our study, patients with resistant HTN received more treatment with statins, 74.4% vs. 49.6% of patients with HTN, and therefore they had lower LDL cholesterol levels. This may be because they are patients with increased cardiovascular risk and with indications for statin therapy regardless of LDL cholesterol levels. In all, 69% of patients with resistant HTN had at least one prior cardiovascular event (coronary disease, episodes of heart failure, cerebrovascular disease and peripheral vascular disease).

The definition of resistant HTN in the 2008 American Heart Association's guidelines includes patients with controlled BP<140/90mmHg who are treated with 4 or more antihypertensive drugs. In our study, close to half of the patients with resistant HTN had adequate control of BP, a figure well above the 19.2% of the primary care register with 6292 hypertensive patients, or in the NHANES substudy where only 27% of patients with CKD had a controlled BP<140/90mmHg.20 Again, this may be due to better treatment compliance and the increased use of aldosterone receptor antagonists in specialised clinics. Lack of treatment compliance, volume overload and activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system21 are the root causes of resistant HTN in patients with CKD. Some studies have already shown that treatment with spironolactone decreases BP regardless of aldosterone levels and plasma renin activity.22 In addition, BP control was associated with a younger age, better kidney function and lower albuminuria.

The study is not without its limitations. Firstly, it is a cross-sectional, observational and prospective study, with the bias that this implies, as the data refer to a single BP reading in the clinic and a single lab test, although it ruled out unstable patients who were hospitalised or who had had a cardiovascular event in the previous 4 months. Secondly, we did not create an ambulatory BP monitoring log or at the patients’ houses with SBMP (self-measured blood pressure monitoring) or with ABPM (ambulatory blood pressure monitoring) at the clinic. Therefore, the prevalence of resistant HTN may be overestimated if important variables such as white coat syndrome or poor compliance by some patients are taken into account. Another limitation of the study is the small sample size and that is was conducted at only one hospital, which involves a bias in patient screening.

Although resistance to antihypertensive therapy has been associated closely with a drop in glomerular filtration rate, there are few studies on the prevalence and epidemiology of refractory HTN in patients with CKD. In these patients, HTN is both the cause and the consequence of CKD.23

We are presenting the first study of prevalence of resistant HTN in a CKD population in Spain, where the association between refractory HTN, proteinuria and degree of CKD is confirmed. Patients with resistant HTN tend to be older, have a high cardiovascular comorbidity and more target-organ damage, and so it is very important to make an early diagnosis and provide proper treatment. Care at a specialised clinic and the development of therapeutic strategies such as careful treatment with spironolactone were associated with a lower prevalence of refractory HTN and better BP control. The use of aldosterone blockers should be assessed in patients with uncontrolled resistant HTN, and with moderate CKD, always at low doses and while monitoring potassium levels. This study opens up options for further studies in patients with CKD and resistant HTN, with a better design (prospective, multicentre, and including a larger number of patients).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Verdalles Ú, Goicoechea M, Garcia de Vinuesa S, Quiroga B, Galan I, Verde E, et al. Prevalencia y características de los pacientes con hipertensión arterial resistente y enfermedad renal crónica. Nefrología. 2016;36:523–529.