Alström syndrome (ALMS) is a very rare autosomal recessive genetic disease that may affect several organs, including the kidney, and be the cause of end-stage renal failure. It is considered a ciliopathy due to mutations in the LAMS1 gene (located on chromosome 2p13), and the first symptoms are observed in childhood.1

The life expectancy rarely exceeds 50 years. Photoreceptor dystrophy is present in 100% of cases, leading to early blindness. There may also be neurosensory hearing loss, truncal obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2), acanthosis nigricans, hypertriglyceridaemia that may cause acute pancreatitis, hypogonadism, polycystic ovary syndrome, hypothyroidism, short stature, dilated cardiomyopathy, kidney failure, lung failure, etc.1–3

The ALMS diagnosis is confirmed with a genetic test, although it is usually clinical using the age-specific major and minor criteria from Marshall,1,2 given the high economic cost of this testing and the limited number of centres where it can be performed.4

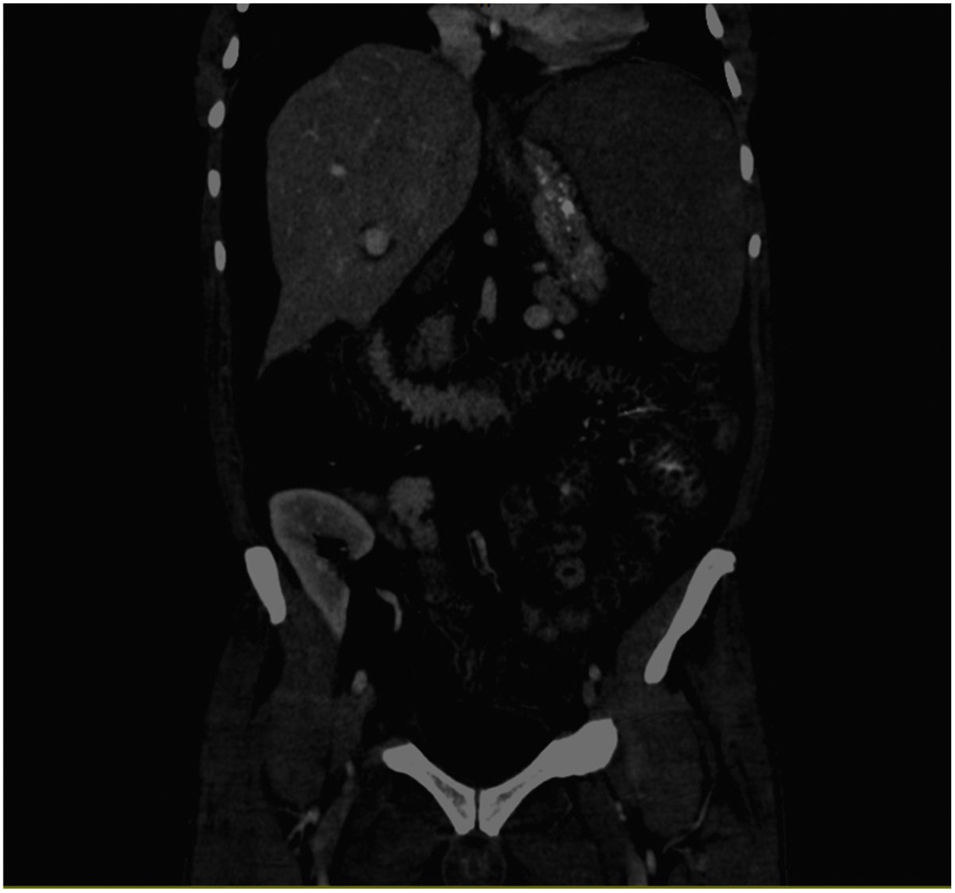

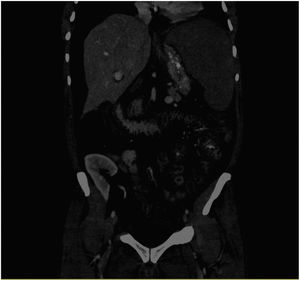

We present the case of a 56-year-old male affected by ALMS (one major criteria: retinitis pigmentosa and four minor criteria: DM2, chronic kidney disease, hypogonadism, and hypertriglyceridaemia. Other supporting data: dental alterations, short and thick neck, hand hypertrophy, and generalised cramps). The patient started haemodialysis in September 2017, and underwent kidney transplantation after one year. He received triple immunosuppressant therapy with tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone, with normal kidney function. There were no heart or liver alterations in the pre-transplant evaluations. In March 2020, he was admitted for pain and abdominal distension. The abdominal computerised tomography (CT) scan showed splenomegaly and oedema of the small intestine and colon walls that suggested enteropathy due to portal hypertension and ascites (Fig. 1). A cholestasis pattern was observed on the laboratory tests, with an increase in transaminases and the ascites fluid testing showed changes compatible with transudate. Hepatic haemodynamic testing showed evidence of a portal systemic gradient of 6 mmHg and the transjugular biopsy showed evidence of mild interphase and lobular portal hepatitis, mild sinusoidal dilation, focal ductal proliferation, and stellate cell portal fibrosis. He remained fasting with administration of parenteral nutrition and intravenous somatostatin. However, his course was torpid, with progressive clinical decline, presenting with fever, profuse coffee ground vomiting, and death within a few days.

Kidney involvement in ALMS is slowly progressive and highly variable, and may not be related to the DM2. It manifests as tubulointerstitial disease with progressive fibrosis. In some patients, kidney transplantation may be contraindicated by the presence of significant complications such as severe cardiomyopathy, morbid obesity, uncontrolled DM2, etc.5 Marshall et al. suggest kidney or kidney-pancreas transplant as a treatment, but there are very few cases reported in the literature.5,6

Gathercole et al. conducted one of the largest studies on liver involvement in ALMS, concluding that there is an increased risk of advanced non-alcoholic fatty liver and adipose tissue fibrosis in these patients.7 The striking clinical course of our patient and the initial absence of liver involvement in the conventional pre-transplant testing (laboratory tests, ultrasound, and abdominal CT scan), leads us to consider whether transient elastography or FibroScan® should be routinely performed in ALMS. It would enable us to assess the degree of liver fibrosis, as well as early quantification of liver fat and monitor its progression in a rapid, non-invasive manner, thus being able to act before any major complications develop.