The risk of developing chronic kidney disease five years after a non-renal solid organ transplant varies in the range of 7%–21%.1 The mechanisms involved include chronic dysfunction of the transplanted organ and previous acute kidney injury with incomplete recovery of renal function. However, the most important mechanism continues to be direct nephrotoxicity from calcineurin inhibitors, added to other factors derived from the use of these drugs that contribute to the progression of chronic kidney disease.2–4

It is estimated that 29% of this population will progress to advanced chronic kidney disease and therefore require renal replacement therapy.2,4,5 The use of peritoneal dialysis (PD) has been limited in these patients for fear of a higher incidence of infectious and non-infectious complications due to immunosuppression, and of possible calcineurin inhibitor-related peritoneal toxicity. Such toxicity can cause changes in the morphology of the peritoneal membrane (neoangiogenesis, vascular hyalinosis, profibrotic changes), but without significant repercussions on peritoneal transport (demonstrated only in animal models).4–6

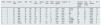

We describe here our centre experience with this group of patients on PD. This was a descriptive observational study that included all patients with a non-renal solid organ transplant who started PD from January 2012 to October 2019. The study group consisted of 10 patients: two liver transplant recipients, one double-lung transplant recipient and seven heart transplant recipients. Their characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no cases excluded after they started on PD. The patients were referred by the transplant medical team of each speciality to our unit, where they were informed of the different renal replacement therapy techniques, ultimately opting for PD. No routine abdominal imaging tests were performed before starting the PD, although liver transplant patients had already undergone these studies as part of their regular monitoring.

Baseline clinical-epidemiological characteristics of non-renal solid organ transplant patients.

| Patient | Charlson | Age, years | Gender | BMI | HTN | DM type 2 | Albumin, g/l | CRP, mg/dl | EGFR, ml/min | Residual diuresis, cc | Transplant | IS | Time from transplant-start PD, months | Time on PD, months | PD modality | Kt/V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | 67 | Male | 23 | Yes | Yes | 33 | 0.6 | 5 | 1,000 | Heart | TC/EVE | 55 | 9 | CAPD | 1.3 |

| 2 | 3 | 53 | Male | 23 | Yes | Yes | 39 | 0.1 | 7 | 1,500 | Heart | TC/EVE | 74 | 10 | CAPD | 1.9 |

| 3 | 4 | 63 | Male | 27 | No | No | 39 | 1.5 | 7 | 500 | Liver | TC | 50 | 26 | CAPD | 1.7 |

| 4 | 5 | 72 | Male | 34 | Yes | No | 29 | 0.7 | 12 | 1,000 | Heart | MMF | 228 | 28 | CAPD | 1.9 |

| 5 | 4 | 69 | Male | 23 | Yes | No | 38 | 0.5 | 8 | 600 | Heart | TC | 46 | 65 | CAPD | 2.5 |

| 6 | 4 | 71 | Male | 28 | Yes | Yes | 32 | 0.4 | 9 | 1,000 | Liver | TC | 20 | 29 | APD | 2 |

| 7 | 1 | 72 | Male | 29 | Yes | Yes | 33 | 1.2 | 16 | 2,000 | Heart | TC/MMF | 8 | 69 | CAPD | 2 |

| 8 | 5 | 75 | Male | 28 | Yes | Yes | 40 | 1 | 10 | 800 | Heart | CisA/MMF | 240 | 14 | CAPD | 2.1 |

| 9 | 1 | 42 | Male | 18 | No | No | 29 | 0.4 | 15 | 1,000 | Heart | TC/MMF | 144 | 6 | CAPD | 0 |

| 10 | 5 | 20 | Female | 18 | Yes | No | 41 | 0.8 | 9 | 1,000 | Lung | TC/EVE | 180 | 4 | CAPD | 3 |

APD: automated peritoneal dialysis; BMI: body mass index; CAPD: continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis; CisA: ciclosporin A; CRP: C-reactive protein; DM: diabetes mellitus; EGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; EVE: everolimus; HTN: hypertension; IS: immunosuppression; MMF: mycophenolate mofetil; PD: peritoneal dialysis; TC: tacrolimus.

According to their body mass index, 80% of the patients were of normal weight and 20% low weight; although albumin is not the best marker of nutrition, 30% had baseline hypoalbuminaemia. The mean time between the transplant and the start of PD was 7.2 years (86.4 months). The majority (90%) were taking a calcineurin inhibitor when the PD was started and no significant differences were observed in the pattern of immunosuppression between the different transplanted organs.

With regard to the baseline peritoneal equilibrium test in these patients, 44% were fast transporters, 33% fast average and 11% slow average. There were no significant changes in the peritoneal equilibrium test at one year compared to baseline. We believe that most of these patients are fast transporters due to a more protracted chronic inflammatory state, with increased peritoneal surface area. Although we did not have inflammatory cytokine measurements, we observed a tendency towards having elevated C-reactive protein.

There were no significant differences compared to the rest of the population on PD at our centre (38% fast transporters, 41% fast average, 13% slow average, 1% slow).

Regarding infectious complications, there were four episodes of peritonitis due to Staphylococcus aureus in the same patient and three exit site infections: two due to Staphylococcus aureus and one due to Serratia marcescens. There were no fungal infections. At present, the rate of peritonitis in the PD population at our centre corresponds to a ratio of 0.38 episodes per patient-year, and the ratio in the solid organ transplant group was 0.1 episodes per patient-year, suggesting that there is no direct relationship with immunosuppression.

One heart transplant patient had an inguinoscrotal hernia a month after starting PD, requiring a temporary transfer to haemodialysis; four weeks after the surgical repair, he restarted the technique without incident. There were no other non-infectious complications.

During follow-up, four patients left the programme: two received a kidney transplant; and two died. The causes of death were complications unrelated to the technique.

PD is now considered comparable to haemodialysis in terms of survival, and may even have advantages over haemodialysis due to the better preservation of residual renal function and less haemodynamic stress.3,4 Those factors could even make it particularly indicated in this group of patients, in whom preserving residual renal function can be complicated in clinical practice.

In conclusion, in our experience, with the limitation of the small sample size, patients with non-renal solid organ transplants do well on PD without any added risk of infectious or non-infectious complications, with good outcomes in terms of safety and adequacy of the dialysis, and no differences in peritoneal transport regardless of the transplanted organ.

Please cite this article as: Andrade López AC, Bande Fernández JJ, Rodríguez Suárez C, Astudillo Cortés E. Diálisis peritoneal en trasplantados de órgano sólido no renal: experiencia en nuestro centro. Nefrologia. 2022;42:210–212.