To the Editor:

Percutaneous biopsy is an essential tool for assessing and managing transplant patients with renal graft dysfunction. However, it is an invasive procedure and, therefore, is not without risk.

Arteriovenous fistula (AVF), associated or not with pseudoaneurysm, following a percutaneous renal biopsy, is an uncommon complication, occurring in between 0.34% and 6.3% of cases.1 Most of these vascular lesions have little clinical relevance and simply require observation and monitoring. However, sometimes they can cause kidney graft dysfunction, high blood pressure or serious bleeding,2,14 requiring urgent treatment.

We report a case of post-renal biopsy AVF and pseudoaneurysm in a transplant patient who presented with haematuria. The vascular lesion was identified by angiography and renal Doppler ultrasound and treated endovascularly by embolisation using micro coils.3

CASE STUDY

Our patient is a 48-year-old female with high blood pressure, diabetes, dyslipidaemia and chronic kidney disease who received a deceased donor kidney transplant. Fifty-seven days after transplantation, she had normal renal function with creatinine of 1mg/dl and without proteinuria. Twenty-six months after transplantation, she sought consultation due to general malaise, decreased appetite, epigastric pain, vomiting and diarrhoea for 3-4 weeks. She had blood pressure (BP) of 156/80mmHg, a heart rate of 82bpm and oliguria. Acute renal failure was demonstrated with creatinine of 12mg/dl, metabolic acidosis and hyperkalaemia (6.75 mmol/l).

We initially suspected acute renal failure secondary to acute graft rejection due to oral intolerance to immunosuppressive drugs, since we observed suboptimal plasma tacrolimus levels. Given this suspicion, we started the patient on corticosteroids and a renal biopsy was performed for histological diagnosis, which displayed lesions compatible with Banff classification type I acute cellular rejection. At biopsy, she had creatinine of 3.51mg/dl and a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 15%.

After the biopsy, the patient developed marked haematuria with clots, although it was not occlusive. A renal Doppler ultrasound displayed a haematoma in the middle lobe with inner blood flow, entry and exit arches, suggestive of AVF.

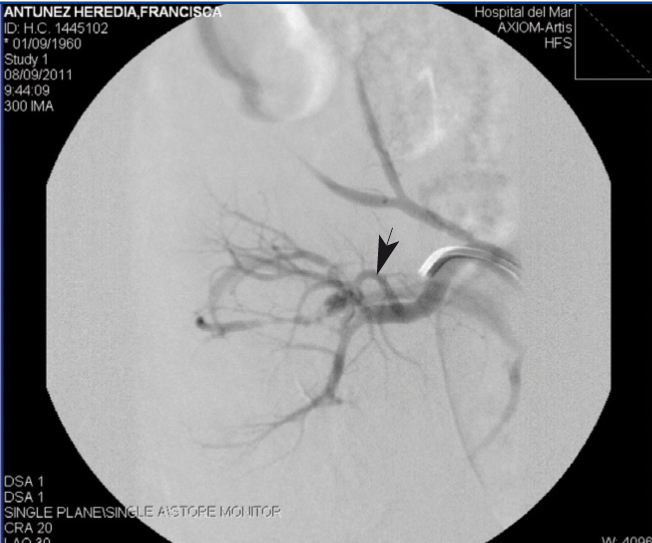

Selective catheterisation was performed on the renal artery by femoral route using a Van Schie catheter. The angiography revealed a segmental renal branch AVF with high-flow and another two smaller AVF dependent on the latter, all in the middle third of the kidney (Figure 1). We proceeded to catheterise the affected renal branch, releasing two 0.5cm (Cook) micro coils to treat the high-flow fistula. The two remaining fistulas thrombosed spontaneously after catheterisation of the affected branch with a multipurpose catheter, prior to a further release of micro coils.

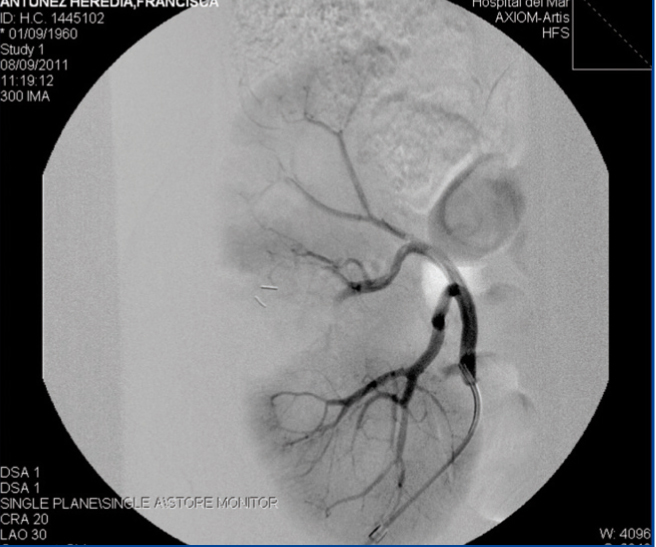

The corroborative angiography showed normal permeability in the remaining renal branches and perfusion of the parenchyma (Figure 2). At this time, the patient had creatinine of 5.23mg/dl and a GFR of 9%. She showed good BP control, between 120-139/70-85mmHg and higher diuresis of 1800ml/day. Post-procedure progression was satisfactory without recurrence of haematuria and a progressive improvement in renal function (after two months, she had creatinine of 2.84mg/dl and a GFR of 20%), as well as resolution of the AVF and pseudoaneurysm.

DISCUSSION

Percutaneous renal biopsy is the method most widely used to obtain renal tissue for diagnosis of renal diseases. The possibility of ultrasound guidance and automated devices have resulted in the more frequent and safer use of this procedure.

Associated complications of this procedure include: perirenal haematoma, haematuria, AVF, pseudoaneurysm and arterio-calyceal fistula. An AVF is formed by a simultaneous lesion to the wall of arteries and adjacent veins, resulting in a communication between the two vessels.

It has been shown that 70% of all AVF are resolved spontaneously within the first 1-2 years and that 30% persist or become symptomatic.8 A persistent AVF can cause haematuria, renal failure and high blood pressure. Haematuria is the most common complication10 and may cause obstructive renal dysfunction.

It is generally accepted that an AVF can be reliably diagnosed by Doppler ultrasound.4 In our case, renal angiography confirmed the AVF and pseudoaneurysm.

Treatment options for symptomatic AVF range from total or partial nephrectomy to selective embolisation of the affected vessels. Nephrectomy may be the only option in a case of severe and uncontrollable acute haemorrhage. Arterial embolisation by catheter has been carried out successfully in recent years and the success rates are around 88%.5,6

Selective embolisation is an effective treatment for post-biopsy AVF.11-13 Its interference with the renal parenchyma is limited and it is less aggressive than open surgery. As such, in our view, it should be considered as the first choice of treatment whenever the urgency of these cases permits.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Figure 1. Selective renal angiography displaying an arteriovenous fistula in the segmental renal branch.

Figure 2. Corroborative renal angiography following embolisation of the arteriovenous fistula with micro coils.