Renal haemorrhage is a potentially life-threatening event requiring emergency surgery. Endovascular therapy is currently the first-line treatment option.

ObjectivesReview patients with renal haemorrhage who required emergency endovascular therapy at our centre. Evaluate the causes of the bleeding, the treatment performed and the clinical outcomes.

Material and methodsWe performed a retrospective analysis of consecutive patients with renal bleeding who underwent endovascular therapy from June 2012 to June 2017 at Hospital Universitari Joan XXIII (Tarragona, Spain). Demographic data (age, gender and comorbidity) and other related variables were collected (mechanism of injury, haemodynamic stability and anticoagulant therapy). We also studied the CT angiography findings, time from diagnosis to surgery, endovascular technique and materials used, extent of tissue embolised and outcomes.

ResultsTwenty-two (22) patients were included with a mean age of 63 (range 19–85). The aetiology of injuries included: renal biopsy (n=7, 31.8%), bleeding from malignant kidney tumour (n=5, 22.7%), trauma (n=4, 18.2%), angiomyolipoma (n=2, 9.1%), spontaneous bleeding (n=2, 9.1%) and surgical complications (n=2, 9.1%). The endovascular therapy technique was embolisation in all cases. The following materials were used: spheres (9.1%); coils (63.6%); spheres+coils (18.2%); and spheres+plug (9.1%). In 17 cases (77.3%), selective embolisation was performed and in five cases (22.7%), embolisation of the whole kidney. Clinical and technical success rates of 100% were recorded. The 30-day mortality rate was 9.1%.

ConclusionWe believe that endovascular therapy is an effective modality for the management of renal bleeding which, in many cases, enables a large part of the renal tissue to be preserved.

Los casos de hemorragia renal que provocan un compromiso para la vida del paciente requieren de una cirugía urgente. Actualmente la cirugía endovascular es el tratamiento de primera elección.

ObjetivoRevisar los pacientes con una hemorragia renal que fueron intervenidos de urgencia mediante una técnica endovascular en nuestro centro. Evaluar las causas de sangrado renal, el tratamiento realizado así como los resultados obtenidos.

Material y métodosRealizamos un estudio retrospectivo de pacientes consecutivos con sangrado renal y que fueron tratados con una técnica endovascular entre junio del 2012 y junio del 2017 en el Hospital Universitari Joan XXIII (Tarragona). Se recogieron los datos demográficos (edad, sexo, comorbilidad) y otras variables relacionadas (mecanismo de la lesión, la estabilidad hemodinámica y si estaba en tratamiento anticoagulante). También se analizaron los hallazgos encontrados en la angio-TAC, el tiempo transcurrido entre el diagnóstico y la realización de la cirugía, la técnica endovascular y el material utilizado, la extensión de parénquima embolizado y los resultados obtenidos.

ResultadosIncluimos a 22 pacientes con una edad media de 63 años (19-85). Las causas de lesión fueron relacionadas con punción de una biopsia renal (n=7,31; 8%), sangrado de tumoraciones malignas renales (n=5; 22,7%), traumatismos (n=4; 18,2%), angiomiolipomas (n=2; 9,1%), sangrado espontáneo (n=2; 9,1%) y complicaciones quirúrgicas (n=2; 9,1%). En todos los casos la técnica endovascular realizada fue la embolización. El material utilizado fue: esferas (9,1%), coils (63,6%), esferas+coils (18,2%), esferas+oclusor (9,1%). En 17 de los casos (77,3%) se llevó a cabo una embolización selectiva y en 5 casos (22,7%) una embolización de todo el riñón. El éxito clínico y técnico fue del 100%. La mortalidad a los 30 días fue del 9,1%.

ConclusiónCreemos que el tratamiento endovascular es una técnica efectiva para el control del sangrado renal y permite, en la mayoría de casos, la preservación de gran parte de parénquima renal.

Renal bleeding is not a common event, but it can be life-threatening and, therefore, requires emergency surgery. Since the first embolisations were performed in 1970 to treat renal artery lesions, use of this technique as a primary treatment and alternative to open surgery has steadily increased.1,2 Its popularity is based mainly on the fact that it is a less invasive way of effectively controlling renal bleeding.1,3

The main objective of this study was to review all patients who required emergency endovascular treatment (EVT) for renal haemorrhage at Hospital Universitari Joan XXIII (Tarragona) in the last five years. Our aim was to assess the main causes of the bleeding, the technique and material used and the outcomes obtained.

Material and methodsFollowing that brief introduction we now move on to analyse the methodology we used, and we will explain the following aspects:

- •

First of all, we conducted a retrospective study of consecutive patients from June 2012 to June 2017 who required emergency EVT for active renal bleeding causing haemodynamic instability or acute anaemia (hemoglogin reduction >2g/L). All the patients were referred from the Urology Department, but in all cases the EVT was performed by the on-call vascular surgery team at our hospital. Patients who were treated on an elective basis and/or who had open surgery were excluded.

- •

With regard to data collection, we focused on the following variables:, demographic data (age, gender and comorbidity); and, variables related to the mechanism of injury, haemodynamic stability, anticoagulant therapy, computerised axial tomography with contrast (CT angiogram) findings (fistulas, pseudoaneurysms [PSA]), time from CT angiogram diagnosis to start of surgery, endovascular technique performed, embolisation material used, type of embolisation (partial or total), technical and clinical success, procedure-related complications and 30-day post-intervention mortality rate.

- •

As far as the technical success of the procedure, we considered that it was favourable when complete sealing of the bleeding was achieved according to the verification arteriogram performed at the end of the procedure. Clinical success was defined as the situation in which the patient did not need any other surgical procedure to achieve cessation of bleeding.

- •

For the study of renal function, glomerular filtration rate was estimated (eGFR) using the Cockcroft-Gault formula.4 In each patient, the eGFR was calculated according to analyses prior (6–12 months) to embolisation and compared to the results post-procedure (6–12 months). Patients who were on renal replacement therapy or patients who died were excluded from the analysis. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as eGFR<60ml/min/1.73m2. The statistical package SPSS was used for the statistical analysis of this variable. Changes in renal function after EVT were analysed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for related samples. A significant difference was considered if p<0.05.

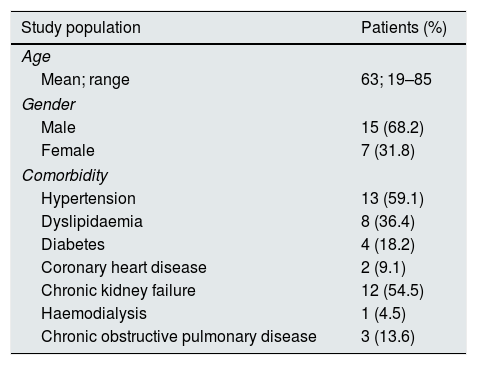

In the five-year period analysed, there were a total of 22 patients who underwent an emergency EVT due to active renal bleeding. The demographic data for the population examined are shown in Table 1; the mean age of the patients was 63 and most of them had CKD.

Characteristics of the study population.

| Study population | Patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean; range | 63; 19–85 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 15 (68.2) |

| Female | 7 (31.8) |

| Comorbidity | |

| Hypertension | 13 (59.1) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 8 (36.4) |

| Diabetes | 4 (18.2) |

| Coronary heart disease | 2 (9.1) |

| Chronic kidney failure | 12 (54.5) |

| Haemodialysis | 1 (4.5) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 3 (13.6) |

All patients had a CT angiogram scan, as intra-abdominal haemorrhage was suspected. Active renal bleeding was found in all cases. Some of the patients also had other lesions in the form of arteriocalyceal fistula (ACF) (9.1%, n=2), arteriovenous fistula (AVF) (13.6%, n=3) and pseudoaneurism (PSA) (9.1%, n=2).

The most common causes of kidney injury were renal biopsy puncture (n=7, 31.8%), bleeding from malignant renal tumours (n=5, 22.7%) and trauma (n=4, 18.2%). Other less common causes were angiomyolipomas (AML) (n=2, 9.1%) and complications of percutaneous nephrolithotomy and partial nephrectomy (n=2, 9.1%). In other cases (n=2, 9.1%), the bleeding was spontaneous, and no apparent cause was found.

Clinically, before treatment, 13 (59.1%) patients were haemodynamically stable and the rest (n=9, 40.9%) were in haemorrhagic shock. In terms of symptoms, 19 patients (86.4%) had low-back pain, seven (31.8%) abdominal pain and seven (31.8%) macroscopic haematuria.

In terms of treatment, after assessing the patient and the lesions found in the CT angiogram, the decision was made jointly with the Urology Department to perform an emergency EVT with embolisation to seal the bleeding and resolve the associated vascular lesions (AVF, ACF or PSA). In patients diagnosed with a malignant tumour (n=5, 22.7%), the affected kidney was embolised using microspheres and microcoils (n=3, 13.6%) or microspheres and a plug (n=2, 9.1%). The rest of the patients (n=17, 77.3%) had selective embolisation. In the cases of AML-related bleeding, the supply vessels were embolised with microspheres (n=2, 9.1%) and in the remaining lesions the damaged artery was embolised with controlled-release microcoils (CRC) (n=17; 77.3%).

The approximate mean time from CT angiogram diagnosis to the start of surgery was 3h (1–10h). All patients on anticoagulant therapy (n=5, 22.7%) had their anticoagulation reversed according to the recommendations of the Haemostasis Laboratory.

Finally, in terms of the outcome of the treatment, in all cases it was possible to contain the bleeding. None of the patients required a second EVT, but it should be added that in one of the cases a repeat arteriogram was performed 12h after the procedure due to progressively worsening anaemia. However, no active bleeding was detected. We would also like to highlight the fact that there were no vascular-access complications. In view of these results, we were able to conclude that there was 100% technical and clinical success.

We complete this section with the EVT-related complications detected in our analysis. In fact, most of the patients (n=16, 72.7%) had clinical signs compatible with post-embolisation syndrome, for which they required symptomatic treatment. Only one of the patients (4.5%), who had embolisation of the entire kidney, had a perirenal abscess which required antibiotic therapy and the placement of a percutaneous drainage and, subsequently, a nephrectomy.

As far as the effects of embolisation on renal function were concerned, in three cases (13.6%) the eGFR could not be studied; two of the patients died (they had CKD) and one was already on permanent haemodialysis. Of the remaining 19 patients (87.6%), nine already had CKD (seven stage 3 and two stage 4) prior to the procedure. In the post-embolisation blood monitoring three of the patients had worsening of their eGFR (two of the patients in stage 3 progressed to stage 4 and one of the patients in stage 4 entered the permanent dialysis programme). One of the patients with a history of stage 3 CKD required occasional dialysis, but their creatinine levels then gradually improved and their eGFR returned to pre-surgery values. In 17 patients (89.4%) renal function was maintained and in five patients (26.3%) their eGFR improved. Comparing the variations in eGFR before and after the EVT, a worsening was found in the mean eGFR, with the difference statistically significant (p=0.025).

With regard to follow-up, the average was 11 months (range 12–72 months). At the first visit (1–2 months after the EVT), all the patients had a simple CT scan or CT angiogram to confirm that the injured artery was completely sealed, check on the haematoma and rule out other procedure-related complications. None of the patients had active bleeding and in all cases the embolised arteries were found to be fully excluded. The only complication detected involved signs of infection of the perirenal haematoma in one of the cases. In the subsequent follow-up visits, most of the patients did not require any further imaging tests. The 30-day mortality rate after the EVT was 9.1% (n=2). The cause of both deaths was related to the cancer (malignant kidney tumour) suffered by these two patients.

DiscussionWe wish to focus primarily on three different aspects in the discussion section: firstly, the causes of renal bleeding; secondly, justification for the use of CT angiography; and, lastly, the treatment and the material used. However, before proceeding, we should point out that our study has a series of limitations. The main limitation is the fact that it is a retrospective study, which generates a bias associated with the collection and temporal analysis of the data. Another limitation is the small number of cases included because this is such a rare disorder. That prevented us from being able to carry out a complex statistical analysis to give validity to the results, and means we need to interpret the results with caution and continue analysing the problem in order to obtain solid conclusions.

As far as the aetiology of renal bleeding is concerned, scientific doctrine emphasises how diverse it can be.5 In relation to our study, we are only highlighting the three most common causes in our series:- Firstly, bleeding caused by a renal biopsy, which involves up to a 58% risk of complications.6–9 Most are resolved with conservative treatment, but where that fails (up to 7%), surgical treatment is required.9,10 The most common vascular complications of renal biopsy are bleeding in the form of subcapsular haematoma and micro- or macroscopic haematuria. Less common are lesions in the form of AVF, ACF and PSA.8–10

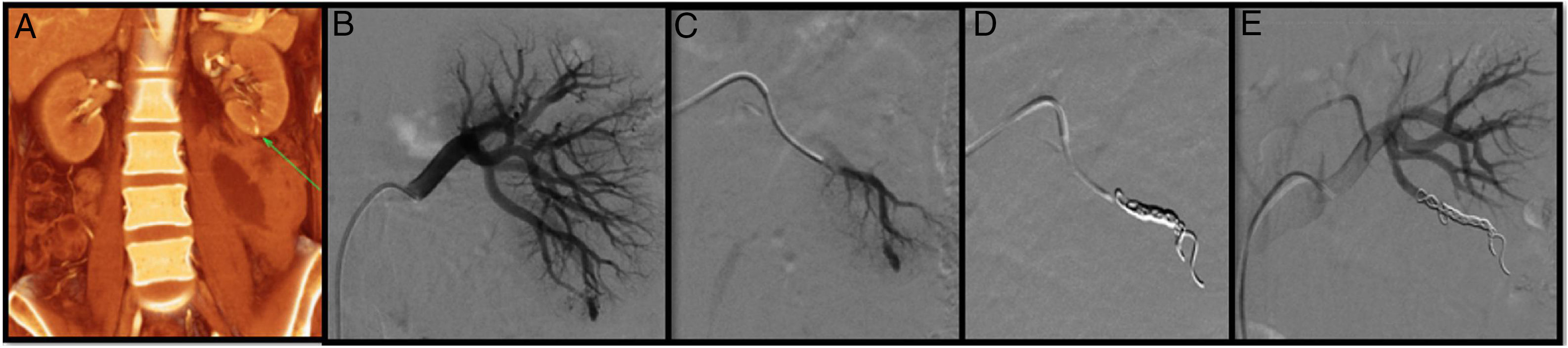

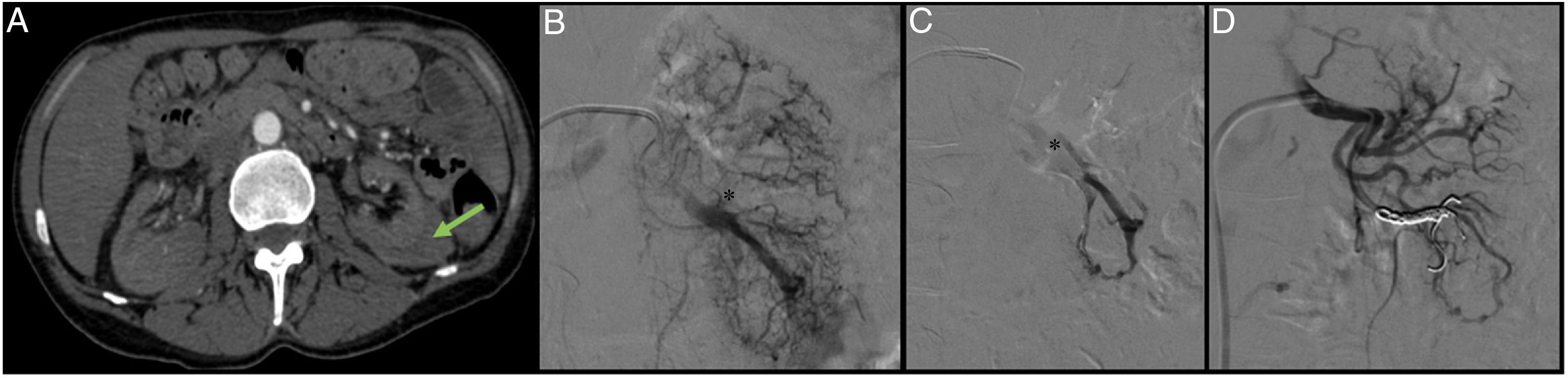

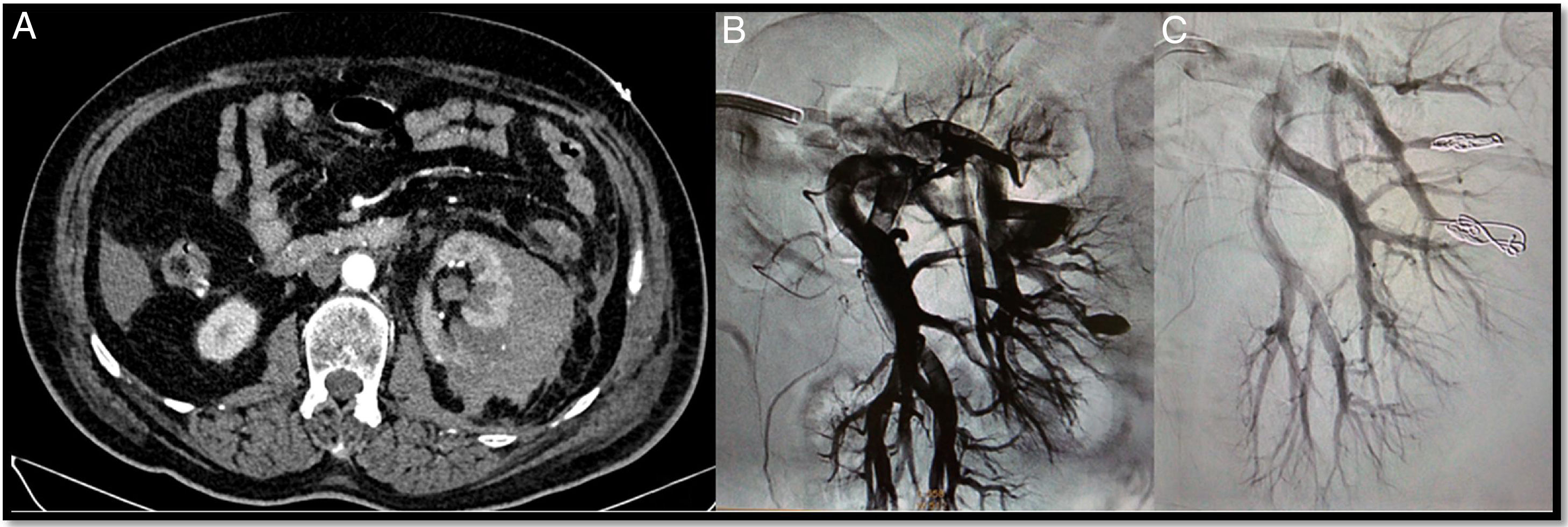

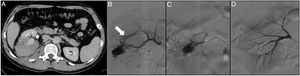

In recent years, as the number of renal biopsies performed at our centre has increased, there has been an associated increase in consultations for renal haemorrhage. In our study, seven cases were found which had active bleeding, in some cases also accompanied by PSA (Fig. 1), AVF (Fig. 2) and ACF. In all cases, selective embolisation of the injured artery with microcoils was the chosen option. The aim of the treatment was always to resolve the bleeding without causing large areas of tissue infarction which might worsen renal function, already impaired in many of the cases.

A 42-year-old woman with a history of lupus, aortic valve prosthesis on treatment with dicoumarol therapy and kidney failure under investigation. Prior to the withdrawal of anticoagulation, a renal biopsy was performed. At 6h after the biopsy, the patient developed intense pain in the left flank with severe anaemia. The CT angiogram shows a retroperitoneal haematoma and a pseudoaneurysm (PSA) (arrow) (A). Through right femoral access and placement of a 6F introducer, the left renal artery was catheterised with the help of a Cobra 5F catheter and a guidewire (0.014″) with atraumatic tip. The subsequent selective arteriogram shows the PSA (B and C). Finally, a 2.7F microcatheter (Progreat, Terumo®) was advanced through the Cobra catheter until it reached the lesion, and it was embolised with controlled-release microcoils (Detach-18, Cook®), with an optimal outcome (D and E).

A 43-year-old patient admitted to the ICU with cerebral haemorrhage in the left basal ganglia in the context of malignant hypertension and end-stage acute kidney injury. A renal biopsy was performed and the patient subsequently developed progressive anaemia. The CT angiogram (A) shows a perirenal haematoma (arrow), for which an arteriogram was performed with the aim of treating the possible lesions. By means of a right femoral puncture and the placement of a 6F introducer, the left renal artery was catheterised with the help of a 4F vertebral catheter and a guidewire (0.014″) with atraumatic tip. The renal artery was then catheterised using a coaxial technique with the help of the 4F vertebral catheter and a 6F guide catheter. A renal arteriogram was performed showing an arteriovenous fistula (AVF) (B and C). A 2.7F microcatheter (Progreat, Terumo®) was advanced and the AVF embolised with controlled-release microcoils (Detach-18, Cook®), with a satisfactory outcome (D).

- Second, spontaneous renal haemorrhage is associated with kidney tumours. This represents 50–60% of retroperitoneal haemorrhages (Wünderlich's syndrome), with benign tumours being the most common cause (31%), followed by malignant tumours (29%).11

AML is the most common type of benign tumour. It is composed of variable amounts of adipose tissue, smooth muscle and dysmorphic blood vessels which predispose to spontaneous bleeding.12 AML larger than 4cm have a 40–50% risk of causing a retroperitoneal haemorrhage, so elective surgery is recommended.5,12 EVT is currently the treatment of choice. Open surgery is reserved only for failed EVT or in cases of diagnostic uncertainty (when a malignant tumour has not been ruled out).

The two patients treated in our series had large tumours, one 7.1cm and the other 5.6cm. As AML is a hypervascularised tumour formed by small vessels, selective embolisation with non-absorbable particles (microspheres) was opted for in order to occlude the smaller vessels which make up the AML and its supply arteries (interlobar arteries).

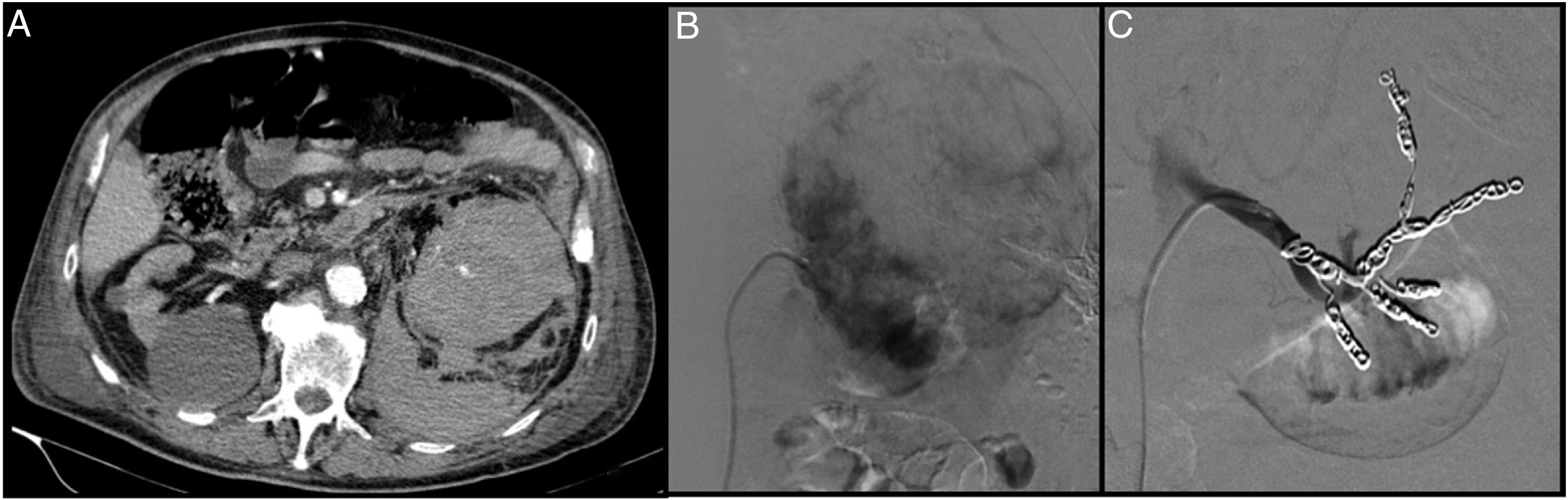

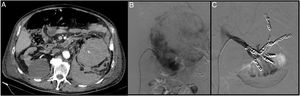

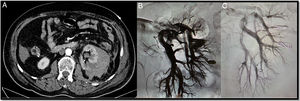

Five patients were treated for bleeding caused by malignant tumours (three cases of clear-cell adenocarcinoma, one of renal metastasis and one of liposarcoma). In all five cases, taking each patient's overall history and prognosis into account, it was decided to perform embolisation of the entire affected kidney. Like AML, malignant tumours are hypervascularised. First of all, therefore, non-resorbable particles (microspheres) were used for occlusion of the smaller and distal vessels, and then coils or plugs to seal the larger vessels (Fig. 3).

An 84-year-old patient diagnosed with renal adenocarcinoma came to Accident and Emergency with abdominal and low-back pain and in haemorrhagic shock. The CT angiogram shows bleeding from a malignant tumour with a large retroperitoneal haematoma (A). Through right femoral access and placement of a 6F introducer, the left renal artery was catheterised with the help of a Cobra 4F catheter and a guidewire (0.014″) with atraumatic tip. The renal artery was then catheterised using a coaxial technique with the help of the 4F vertebral catheter and a 6F guide catheter. Arteriogram with manual contrast injection through the guide catheter shows the large tumour with areas of active bleeding (B). From the vertebral catheter placed in the ostium of each segmental artery, the distal bed was then embolised with the injection of microspheres (300–500μm). Lastly, the segmental arteries and the renal artery were embolised with controlled-release coils (Azur, Terumo®) (C).

- Third, bleeding due to kidney trauma. The degree of kidney injury was classified according to the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) scale.5 The most appropriate management for this type of injury has been debated for years. It would seem that currently the trend is towards conservative treatment for grades 1, 2, 3 and 4, provided the patient is haemodynamically stable.13 If the patient is unstable haemodynamically or has persistent bleeding, AVF or PSA, EVT is recommended. In grade 5 (burst kidney/pedicle avulsion) or in kidney injuries with associated damage in other viscera, open surgery is indicated.3,14,15

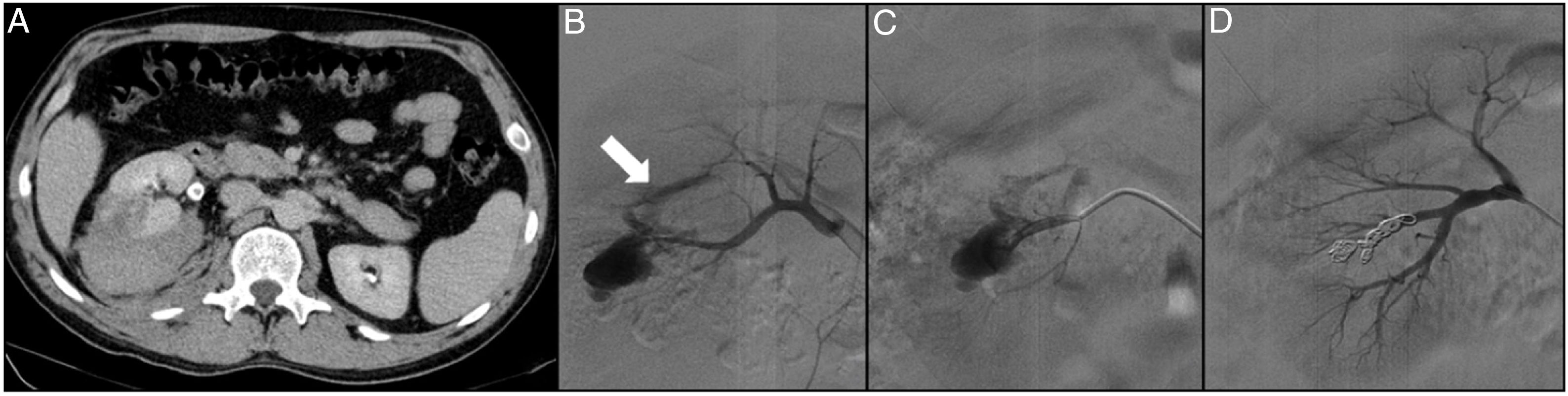

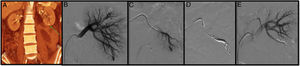

At our hospital, a total of four cases with a history of kidney trauma were treated endovascularly. According to the AAST scale, three of the patients had grade 3 kidney injuries and one had a grade 4 injury. Conservative management was tried initially in three cases, but was not effective, so they subsequently had EVT. In one of the cases, EVT was indicated directly (due to haemodynamic instability). All the cases were treated with selective embolisation using controlled-release microcoils (Fig. 4).

A 31-year-old patient with no relevant medical-surgical history who came to Accident and Emergency with low-back pain and frank haematuria. The patient reported a history of blunt-force trauma to the right lower back 48h previously. The CT angiogram shows a right renal laceration, a retroperitoneal haematoma, an arterial lesion with active bleeding, right pyelo-ureteral dilation with occupation of the urinary tract by blood clots (A). Through left femoral access and the placement of a 6F introducer, the right renal artery was catheterised with the help of a Multipurpose 4F catheter and a guidewire (0.014″) with atraumatic tip. The selective arteriogram shows active bleeding of the inferior segmental artery and an arteriocalyceal fistula (arrow) (B). The injured segmental artery was then catheterised with a 2.7F microcatheter (Progreat, Terumo®) (C) and embolised with controlled-release microcoils (Detach-18, Cook®), resolving the bleeding and excluding the fistula (D).

In all the cases described above, we used CT angiogram as first-order diagnostic imaging test. We opted to use this technique for the following reasons:

- In patients with a history of kidney trauma (n=4, 18.2%) a simple CT and a CT angiogram in the arterial and venous phases helps define the degree of injury according to the AAST scale. In the case of patients with multiple contusions, the CT scan also enables us to rule out associated damage.3,12,13 For these situations, ultrasonography detects free fluid and renal haematomas, but does not identify the degree of the parenchymal injury.16

- In patients with AML bleeding (n=2, 9.1%), spontaneous renal bleeding (n=2, 9.1%) and bleeding from malignant renal tumours (n=5; 22.7%), the CT angiogram made it possible to pinpoint suspected intra-abdominal bleeding more accurately.

- In cases of bleeding due to postoperative complications of urological surgery (percutaneous nephrolithotomy and partial nephrectomy [n=2, 9.1%]), CT angiogram helped define the type of treatment necessary, whether open or endovascular surgery (Fig. 5).

A 74-year-old postoperative patient after left upper partial nephrectomy who had frank haematuria with progressive and persistent anaemia requiring multiple transfusions. The CT angiogram (A) shows a left retroperitoneal-perirenal haematoma with two images suggestive of pseudoaneurysms. Through right femoral access and placement of a 6F introducer, the left renal artery was catheterised with the help of a 4F vertebral catheter and a guidewire (0.014″) with atraumatic tip. A selective arteriogram showed two pseudoaneurysms (B). The microcatheter 2.7F (Progreat, Terumo®) was then advanced through the vertebral catheter to the pseudoaneurysms and they were embolised with controlled-release microcoils (Detach-18, Cook®), with an optimal outcome (C).

- CT angiogram was also performed in patients with injury from renal biopsy puncture (n=7, 31.8%). In these cases, after considering ultrasound as an alternative test, we currently believe that, alongside analysis of the symptoms and laboratory tests, ultrasound can be useful for confirming the diagnosis of bleeding, and can therefore avoid the use of CT angiogram.

To conclude, we should add that, due to the critical situation the patients were in, the risks of contrast-induced nephropathy were accepted in each case. Nevertheless, to mitigate the risks, patients were subsequently given hydration with normal saline and the use of nephrotoxic drugs was avoided.

Lastly, we should begin the discussion of the treatment and materials used with a reminder that most renal haemorrhages (regardless of cause) resolve with conservative measures (complete rest, volume replacement, red blood cell transfusion and reversal of anticoagulation).3,17 In cases where conservative treatment is not effective or the patient's life is in danger, emergency surgery is required. EVT is considered the first-choice treatment because it achieves cessation of bleeding and is minimally invasive.3,11

In that context, the following characteristics were taken into account when choosing the embolising agents: the type of injury, the size of the vessel and the operator's experience with the material and preferences. Because the aim has always been, as far as possible, to reduce the risk of recurrence of the bleeding, non-resorbable materials were used in all cases. No biodegradable material was used. In all cases in which coils were used, it was preferred that they be controlled-release as we believe they are safer and more accurate than coils which are not controlled-release.18 In our series of patients, the use of controlled-release coils meant we were able to reposition them until we achieved the desired position and packing density.

We reviewed the literature to determine the materials other healthcare professionals use to treat renal bleeding and found that most of them also use microcoils for sealing bleeding vessels, and to treat AVF, ACF and PSA lesions. The embolisation is also always made as selective as possible.3,13,19 However, in cases of embolisation of renal tumours (malignant or benign), some surgeons tend to use other materials which, like the microspheres, allow more distal diffusion of the material towards the small vessels; for example, liquid agents (N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate, Ethanol, Ethibloc, Bucrylate, Sotradecol foam or Lipiodol) or other types of particles (Ethanol, Polyvinyl alcohol, Gelfoam).11,12,14,20

In spite of the factors discussed above, we must also mention some of the possible complications deriving from EVT. One of these is post-embolisation syndrome, which occurs in up to 90% of cases. This can involve flank pain, pyrexia, nausea, vomiting and leucocytosis, and onset is usually within the first three days after embolisation is performed.3,5,12,21 Treatment is symptomatic; generally analgesics, antiemetics or antipyretics. In line with the figures reported in the literature, 73% of the patients in our series had clinical signs compatible with post-embolisation syndrome.

Other, much less common, complications (affecting less than 2% of cases) are PSA formation in the artery used as vascular access, liquefaction or necrosis of the renal parenchyma, abscesses, unwanted embolisation due to material migration or incomplete embolisation.3,12 In our series, only one complication of this type occurred. A patient developed an abscess due to infection of the perirenal haematoma.

Last of all, another possible EVT-related complication is worsening of renal function. Although a statistically significant worsening of the eGFR was found among the cases in our study, the literature reviewed suggests that there is little or no significant deterioration in the mean glomerular filtration rate after selective embolisation.7,11,12 This difference may be explained by the analysis jointly of patients treated with selective embolisation and patients whose entire kidney was embolised.

ConclusionRenal haemorrhage can be life-threatening or lead to severe functional sequelae in some cases, so urgent intervention is required. In view of the high morbidity and mortality rates among these patients, we believe that minimally invasive treatment to control the haemorrhage is the best option in the majority of cases. We have confirmed in our series that the use of EVT enabled us to resolve renal bleeding without serious complications which emergency open surgery could have caused. Moreover, in most cases, selective embolisation is possible, enabling a large part of the renal parenchyma to be preserved. Consequently, we believe that we should continue using endovascular techniques to treat patients with renal bleeding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Pantoja Peralta C, Badenes Gallardo A, García Vidal R, Rodríguez Espinosa N, Pañella Agustí F, Gómez Moya B. Nuestra experiencia en el tratamiento urgente de la hemorragia renal. Nefrologia. 2019;39:301–308.