The early detection of Fabry nephropathy is of interest to us. Its treatment is more effective in early stages. It has been studied by analysing molecular and tissue biomarkers. These have certain disadvantages that hinder its routine use. The aim of this study is to describe the role of the nephrologist in the diagnosis of the disease, and to describe the clinical variables associated with nephropathy in affected patients.

Material and methodsCross-sectional study. Patients were included from three reference centers in Argentina.

ResultsSeventy two patients were studied (26.26±16.48years): 30 of which (41.6%) were men and 42 of which (58.4%) were women; 27 pediatric patients and 45 adults. Fourteen “index cases” were detected, 50% of which were diagnosed by nephrologists. Nephropathy was found in 44 patients (61%): 6 pediatric patients and 38 adults. Two types of clinical variables were associated with nephropathy: (i) peripheral nervous system compromise (P≤0.001), angiokeratomas (P≤0.001) and auditory compromise (P=0.01–0.001), with these being early clinical manifestations of the most severe disease phenotype, and (ii) structural heart disease (P=0.01–0.001) and central nervous system compromise (P=0.05–0.01), which are major and late complications, responsible for increased morbidity and mortality and lower life expectancy.

ConclusionThe nephrologist plays an important role in the diagnosis of Fabry nephropathy, although the detection thereof owing to its renal involvement would represent a late diagnosis, because nephropathy is associated with late complications of the most severe disease phenotype.

La detección temprana de la nefropatía por enfermedad de Fabry es de interés, pues su tratamiento es más eficaz en estadios precoces. Ha sido estudiada por biomarcadores moleculares y tisulares, pero estos poseen desventajas que dificultan su uso rutinario. El propósito del presente trabajo es describir el rol del nefrólogo en el diagnóstico de la enfermedad y las variables clínicas asociadas a nefropatía en pacientes afectados.

Material y métodosEstudio transversal. Se incluyeron pacientes de tres centros de referencia de Argentina.

ResultadosSe estudiaron 72 pacientes (26,26±16,48años): 30 (41,6%) varones y 42 (58,4%) mujeres; 27 pediátricos y 45 adultos. Se detectaron 14 «casos índice», el 50% diagnosticados por nefrólogos. Se halló nefropatía en 44 pacientes (61%): 6 pediátricos y 38 adultos. Dos tipos de variables clínicas se asociaron a nefropatía: a)compromiso del sistema nervioso periférico (p≤0,001), angioqueratomas (p≤0,001) y compromiso auditivo (p=0,01-0,001), siendo estas manifestaciones clínicas tempranas del fenotipo más severo de la enfermedad, y b) cardiopatía estructural (p=0,01-0,001) y compromiso del sistema nervioso central (p=0,05-0,01), que son complicaciones mayores y tardías, responsables de la morbimortalidad aumentada y la menor expectativa de vida.

ConclusiónEl nefrólogo cumple un rol importante en el diagnóstico de la enfermedad de Fabry, ya que aunque la detección de esta por su compromiso renal significaría diagnóstico tardío, debido a que la nefropatía se asocia a complicaciones tardías del fenotipo más severo de la enfermedad.

Fabry disease (FD, OMIM 301500) is one of the lysosomal deposit diseases (LDD). This group of diseases includes at least 50 hereditary entities of low frequency, originated by a congenital error of the metabolism secondary to a specific monogenic defect that results in a deficiency in the activity of a lysosomal enzyme.1 This enzyme deficiency causes the accumulation of not metabolized substrates primarily in the lysosomes and then, progressively, in other cellular compartments.1,2

In FD, since the fetal stages of life, the absence or the reduced activity of enzyme-galactosidase-A (α-gal-A, EC 3.2.1.22) produces the multisystemic accumulation of glycosphingolipids, mainly globotriaosylceramide (Gb3).2

The reported incidence of FD is in the range of one case per 476,000 to one case per 117,000 live births in the general population,2 although neonatal screening in Italy and Taiwan have reported higher results.3,4 Studies of prevalence report FD exist in 0.33% in men and 0.1% in women with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) of unknown etiology.5

Abnormal deposition of non-metabolized substrate affects virtually all tissues and organs, but it is more predominant in the endothelium and smooth muscle cells of blood vessels, along with renal epithelial cells, cardiomyocytes and neural cells.2 The lysosomal storage of Gb3 produces a cascade of deleterious phenomena among which are the compromise of energy metabolism, the injury of small vessels, the dysfunction of ion channels in endothelial cells, the increase of oxidative stress, the alterations of autophagy, tissue ischemia and fibrosis.2,6

The globotriaocilesfingosina (Lyso-Gb3), product of the abnormal metabolism of Gb3, is elevated in patients with FD. Among its recognized effects are: (a) inhibition of enzymatic activity α-gal-A; (b) the release of chemical mediators of glomerular damage, and (c) stimulation of vascular proliferation, with thickening of the intima-media.7–9

In the kidney, progressive deposits of Gb3 affect tubular, glomerular (including podocytes), endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells. This has been demonstrated in renal biopsies of patients even without clinical manifestations of kidney involvement.10,11

The first symptoms of EF are expressed during childhood, with acroparesthesias, episodes of neuropathic pain in all four limbs, hypohydrosis, recurrent abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea and early satiety, and angiokeratomas. During adolescence, cornea verticillata, dysautonomic manifestations and decreased hearing ability. Upon adulthood, renal, cardiac and cerebrovascular disease develops, with increased morbidity and mortality and a decrease in life expectancy as compared with the general population.2

Until the year 2001, renal failure was described as the main cause of death in the FD.12 Subsequently, it was reported that the main cause of death is cardiovascular (57% of cases), that patients dying from cardiovascular causes had previously received dialysis therapy and have had a late diagnosis.13 For this reason, the research work of nephropathy in patients with FD, its mechanisms, evolution and treatment, has been a topic of relevance among experts.14–20 Early detection of nephropathy is important because specific treatments for FD are more effective in early stages of kidney damage, decreasing its effectiveness in advanced stages of CKD, mainly due to the development of fibrosis.6,21

The nephropathy of FD has been studied with both molecular and tissue biomarkers,17,22–24 which have advantages and disadvantages for use in routine practice. The scarce accessibility of highly complex methods in some geographical areas and the complications of invasive methods make it difficult for the use in routine clinical practice.25 The purpose of this paper is to describe the role of the nephrologist in the early diagnosis of FD and the clinical variables associated with nephropathy in affected patients.

Material and methodsCross-sectional design with retrospective data collection. Preliminary data of the present study have been previously published.26

The study was approved by each local ethics committee. The patients of legal age, with inclusion criteria, signed the informed consent. The minors gave their consent, and the informed consent was signed by their tutor or legal representative in accordance with local regulations.

Patients with probable diagnosis of FD from June 2007 to September 2017 were recruited from three reference centers in Argentina: (a) Neurosciences Center Los Manantiales, Grupo Gamma Rosario, Rosario, Province of Santa Fe; (b) Infusion Center and Study of Lysosomal Diseases of the Pergamino Clinical Nephrology Institute, Pergamino, Province of Buenos Aires, and (c) Intensive Therapy Service of Dr. Enrique Erill de Escobar Hospital, Belén de Escobar, Province of Buenos Aires. Patients included had diagnosis of FD confirmed by genetic study and enzyme dosage α-gal-A were. Exclusion criteria: patients with nephropathy of other etiology different from FD. Criteria for elimination: patients with inclusion criteria who refuse to participate in the study or who present a complication related to the extraction of blood or with diagnostic studies during its execution. Pathogenic mutations of the GLA gene were detected by genetic study, by direct sequencing and Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA).27,28 The measurement of α-gal-A activity was performed by fluorometric method,29 and was considered normal or decreased if it was above and below 4.0nmol/h/l respectively. Creatinine in plasma and urine was determined by electro-chemiluminescence Roche Diagnostics. The eGFR was calculated using the Schwartz equation and the CKD-EPI in patients under and over 21 years of age, respectively.30,31 The Kidney Disease classification was used to stage the eGFR: Improving Global Outcomes Chronic Kidney Disease Guideline 2013 (KDIGO).32 Albuminuria was determined by the Roche Diagnostics colorimetric method.33 The albumin/creatinine ratio in urine was used to estimate the urinary excretion of proteins in 24h. Values from 0 to 30 were considered normal, from 30 to 300 microalbuminuria and greater than 300 albuminuria, in at least two urine samples.33 The nephropathy in adults was defined by: (a) microalbuminuria or albuminuria, and/or (b) GFR less than 90ml/min/1.73m2, and/or (c) the history of kidney function replacement therapy by dialysis or transplant. The nephropathy in pediatric patients was defined by the presence of microalbuminuria or albuminuria; the changes in eGFR were not considered due to the limitations of the calculation of the eGFR in pediatric patients with formulas that use serum creatinine.34 The proportion of index cases diagnosed by a specialist in nephrology was determined. We used the classic definitions of cardiovascular risk factors.35 Peripheral nervous system (PNS) involvement was considered due to the presence of neuropathic pain typical of FD or alterations of the quantitative sensory testing (QST).36 Gastrointestinal involvement was established by the presence of abdominal pain, recurrent diarrhea, nausea or early satiety in relation to intake without any other cause than FD.2,37 The cornea verticilata was evidenced by ophthalmological examination with a slit lamp.2,38 The angiokeratomas were evaluated by a dermatologist with experience in FD.2 The auditory abnormalities were evaluated by logo-audiometry.2 The cardiac involvement was differentiated into: (a) arrhythmias, and (b) structural cardiomyopathy, since both alterations occurred in pediatric and adult patients. Arrhythmias were defined by the presence of electrophysiological alterations in electrocardiogram (12 leads ECG). Structural heart disease was defined by the presence of LV hypertrophy in color Doppler echocardiography and/or typical images in magnetic nuclear resonance (MRI) with gadolinium.2,39 The involvement of the central nervous system (CNS) was defined by the history of Stroke and/or typical images in asymptomatic brain MRI.2,40

Statistical analysisDependent variable: nephropathy. Independent variables: gender, age, α-gal-A activity, peripheral neuropathy, gastrointestinal compromise, cornea verticilata, angiokeratomas, auditory alterations, arrhythmias, structural heart disease, CNS compromise, hypertension (HTN) and smoking. The odds ratio was calculated for the two variables considered risk factors for nephropathy in patients with FD: α-gal-A activity, HTA.15,41

The data was processed on a SPSS statistics 20 databaseTo determine the association between the dependent variable and independent variables (nominal variables), the chi-square test was used with data organized in contingency tables. No Yates correction factor was used since sample was greater than 40, nor exact Fisher test for expected frequencies greater than 5. We worked with a 95% confidence interval. For the calculation of P, the chi-square distribution table was used according to the degree of freedom. P<0.05 values were considered of statistical significance to reject the null hypothesis (Table 1).

Frequency distribution and association between nephropathy and the independent variables studied.

| Variable | Value | With nephropathy | Without nephropathy | Chi2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 20 | 10 | 1.03 | 0.3–0.5 |

| Woman | 23 | 19 | |||

| Age | Pediatric | 6 | 21 | 27.49 | <0.01 |

| Adult | 38 | 7 | |||

| Activity α-gal-A | Normal | 21 | 13 | 0.01 | >0.95 |

| Decreased | 23 | 15 | |||

| Involvement of PNS | Yes | 34 | 5 | 13.53 | <0.001 |

| No | 10 | 18 | |||

| Involvement of GI | Yes | 12 | 5 | 0.84 | 0.3–0.5 |

| No | 32 | 23 | |||

| Cornea verticilata | Yes | 12 | 10 | 0.57 | 0.3–0.5 |

| No | 32 | 18 | |||

| Angiokeratomas | Yes | 20 | 6 | 13.53 | <0.001 |

| No | 24 | 22 | |||

| Auditory abnormalities | Yes | 19 | 3 | 8.5 | 0.01–0.001 |

| No | 25 | 25 | |||

| Arrhythmias | Yes | 5 | 3 | 0.01 | >0.095 |

| No | 39 | 25 | |||

| Structural heart disease | Yes | 18 | 2 | 9.72 | 0.01–0.001 |

| No | 26 | 26 | |||

| Involvement of the CNS | Yes | 14 | 2 | 6.03 | 0.05–0.01 |

| No | 30 | 26 | |||

| HTN | Yes | 18 | 1 | 12.28 | <0.001 |

| No | 26 | 27 | |||

| Smoking | Yes | 6 | 0 | 4.17 | 0.05–0.01 |

| No | 36 | 28 | 1.03 | 0.3–0.5 | |

HTN: hypertension; CNS: central nervous system.

A total of 72 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of PE were studied (26.3±16.5 years), 30 (41.6%) were men. There were 27 (37.5%) pediatric patients and 45 (62.5%) adults.

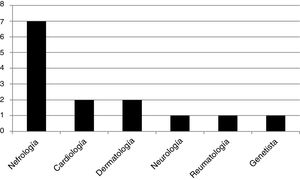

We found 13 genotypes: E398X, L415P, M296V, L106R, R227Q, A292T, C.448.delG, R363H, C382Y, R301Q, D109G, from 3 and 4 exons, W81X, all pathogenic mutations of the GLA gene. We studied 14 patients that were “index case”: 12 men and 2 women, all adults. A 50% of them were diagnosed by a nephrologist, 14.5% by a cardiologist, 14.5% by a dermatologist, and the rest, 7% by each specialty: neurology, rheumatology and geneticist. The frequency distribution is shown in Fig. 1. Of the 12 male index cases, 11 patients presented kidney damage (5 patients had ESRD). The two index case women did not present kidney damage.

All of the index cases presented the classic phenotype of the disease, the typical early manifestations of childhood were seen in 100% of them. The prevalence of major events typical of adulthood in FD in the index cases group was as follows: (a) one patient (6.00%) presented a major event; (b) 7 patients (46.6%) presented two major events, and (c) 6 patients (40.0%) had three major events.

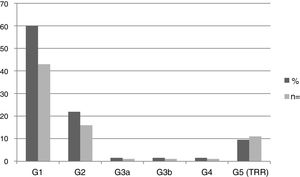

Nephropathy was found in 44 patients (61.1%): 6 pediatric patients and 38 adults. The mean eGFR in the pediatric population was 115.8±20.8ml/min/1.73m2, and in adults, 80.6±42.2ml/min/1.73m2. Fig. 2 shows the frequency distribution of nephropathy according to the KDIGO stage. 100% of patients in stages G3, G4 and G5 were male.

Smoking and hypertension were the only cardiovascular risk factors present in the study population.

Table 1 shows whether there is a significant relationship between patients with or without nephropathy (dependent variable) and a series of descriptive (independent) clinical variables. Table 2 shows the odds ratio values calculated for the exposure factors for the dependent variable (nephropathy): decreased α-gal-A, HBP and smoking.

Calculation of odds ratio for the three exposure factors of nephropathy: enzymatic activity, HTN and smoking.

| Variable | OR | z statistics | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-gal-A decreased | 0.949 | 0.108 | 0.9143 |

| HTN | 18.699 | 2.753 | 0.0059* |

| Smoking | 9.623 | 1521 | 0.1282 |

Nephropathy is one of the major complications in FD.26 It is characterized by proteinuria and a progressive decrease in the eGFR.2,26 The decrease in eGFR over time is directly related to the degree of proteinuria and, without therapeutic intervention, is more pronounced in patients with an initial eGFR of less than 60ml/min/1.73m2.15 In our population, 18% of the patients presented eGFR less than 60ml/min/1.73m2 at the time of diagnosis. HTA and male sex have been described as risk factors for nephropathy in patients with EF.15

Due to the progression of nephropathy in FD, the affected men presented with ESRD requiring renal replacement therapy at the mean age of 42 years14 which coincides with the age of inclusion in dialysis of all our patients with ESRD.

In FD nephropathy it is assumed that the initial damage is produced by the abnormal deposit of non-metabolized substrate, Gb3 and its metabolites.2,20 This leads to a cascade of events that include the compromise of energy metabolism, the injury of small vessels, the dysfunction of ion channels in endothelial cells, the increase of oxidative stress, the alterations of autophagy, ischemia and its final result, tissue fibrosis.2,6,20 The plasma concentration Lyso-Gb3, the main metabolite of Gb3, is able to induce induces autocrine TGF-β1 and Notch-1 signals in podocytes, similar to the podocyte response to high glucose levels,8,42 signals that also lead to renal fibrosis.6

Enzyme replacement therapy is the only specific treatment for FD that has been shown to reverse the accumulation of Gb3 in renal tissue, including podocytes, in a dose-dependent manner.43 Its efficacy is greater if stated early, due to the impossibility of correcting the progression when irreversible lesions such as fibrosis are present.6,21,44 Pharmacological chaperones have shown significant histological changes in capillary interstitial cells, but not in podocytes.45

Renal fibrosis has been demonstrated in patients with normal renal function and without albuminuria,10,11,16 and both molecular and histological biomarkers have been studied in prealbuminuric stages of FD nephropathy.8,10,11,16,17,22–24 The high complexity and cost of some of the non-invasive methods and the complications of invasive procedures make routine use difficult, so we propose a model that may be valid to predict the association between clinical variables associated with nephropathy and that helps in the early detection of kidney damage in affected patients, through the simple association of clinical data.

In the natural evolution of FD, there is a progressive multisystemic tissue deposition of Gb3.2 This concept coincides with the results found in our study, in which there was significant association between nephropathy and the age of the patients. In the early stages of tissue damage, patients remain asymptomatic, until substrate deposits and tissue damage reach a critical level and clinical manifestations occur due to organic dysfunction.2 Two types of clinical variables were associated with statistical significance to nephropathy in our patients: (a) peripheral neuropathy, angiokeratomas and auditory compromise, clinical manifestations of the classic phenotype (more severe) of FD and (b) structural cardiopathy and CNS involvement, which are major complications, together with nephropathy in affected adult patients; these are responsible for the increased morbidity and mortality and the lower life expectancy. Both types of variables are not early manifestations in patients with FD.

ConclusionsMen with FD present advanced nephropathy at the time of diagnosis, and the nephrologist plays an important role in the diagnosis. There were no diagnoses of index case in pediatric stages.

As demonstrated in this study, the association of clinical manifestations as variables related with nephropathy could mean the recognition in late stages of kidney damage. It would seem reasonable to continue the search for biomarkers capable of help to make the diagnosis of nephropathy in early stages, which would effectively modify the prognosis of patients affected by this disease.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the content of the submitted work.

Please cite this article as: Jaurretche S, Antongiovanni N, Perretta F. Nefropatía por enfermedad de Fabry. Rol del nefrólogo y variables clínicas asociadas al diagnóstico Nefrologia. 2019;39:294–300.